Access for All

A new generation's challenges on the California coast

A report on research by Jon Christensen, University of California, Los Angeles, and Philip King, San Francisco State University

What the Coast Means to Californians

And how often they visit

The California coast is a special place:

- The vast majority of Californians—90 percent—surveyed in a recent statewide poll told us that the condition of the ocean and beaches is important to them personally, with 57 percent saying it is "very important." There is broad agreement across voter subgroups about the importance of the coast, with majorities of voters of all age, ethnic, and income groups, as well as voters in coastal and inland counties, confirming that the condition of California's ocean and beaches is important to them.

- Our coast and beaches are among our most democratic spaces. Three out of four Californians—77 percent—said that they visit the coast of California at least once a year. Many come more often. One in four say that they visit the coast once a month or more, while another 38 percent visit several times a year.

- But 62 percent say that limited public access to the coast and beaches is a problem, and lack of affordable options for parking and overnight accommodations as well as limited public transportation to the beach are even bigger problems.

- In this interactive report, we explore California beachgoers' views of the coast and a new generation of challenges that Californians face accessing the coast. And we offer recommendations for improving the coastal access guaranteed to all of us by our state constitution and the California Coastal Act.

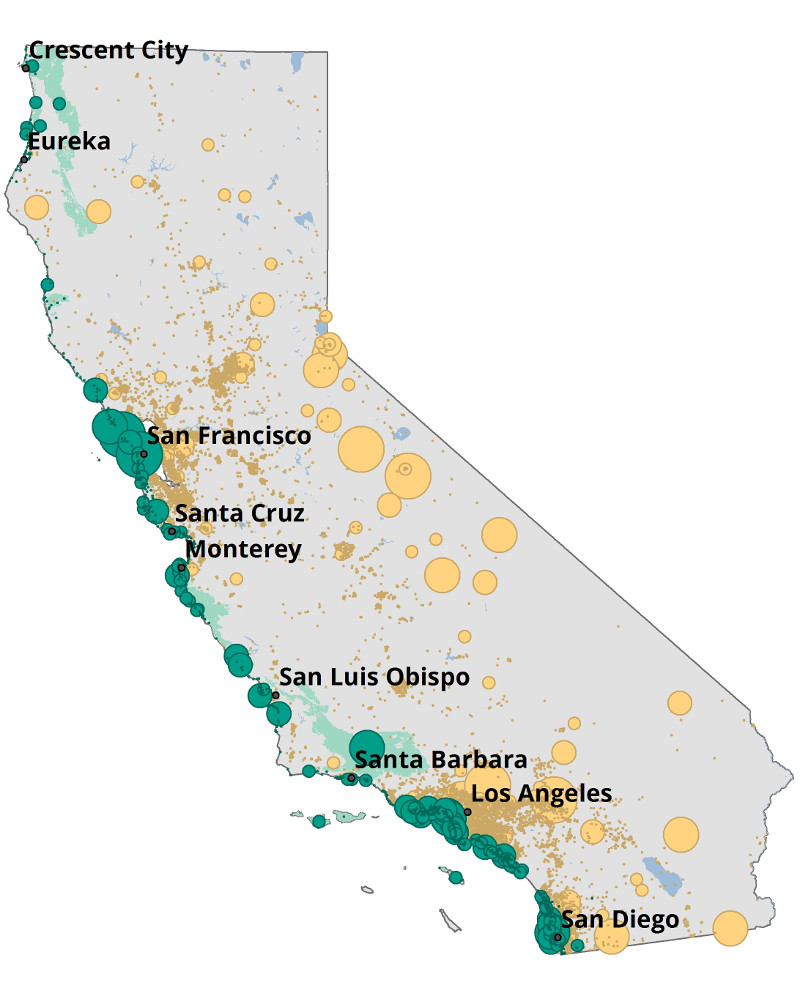

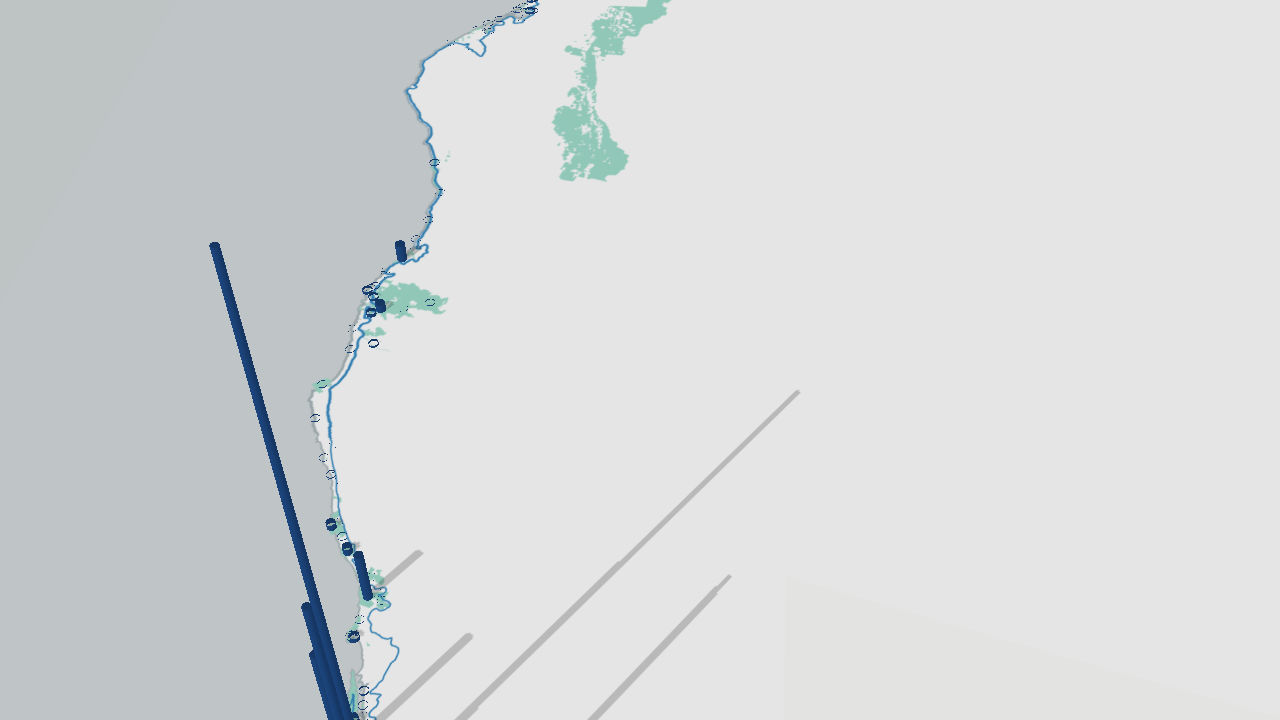

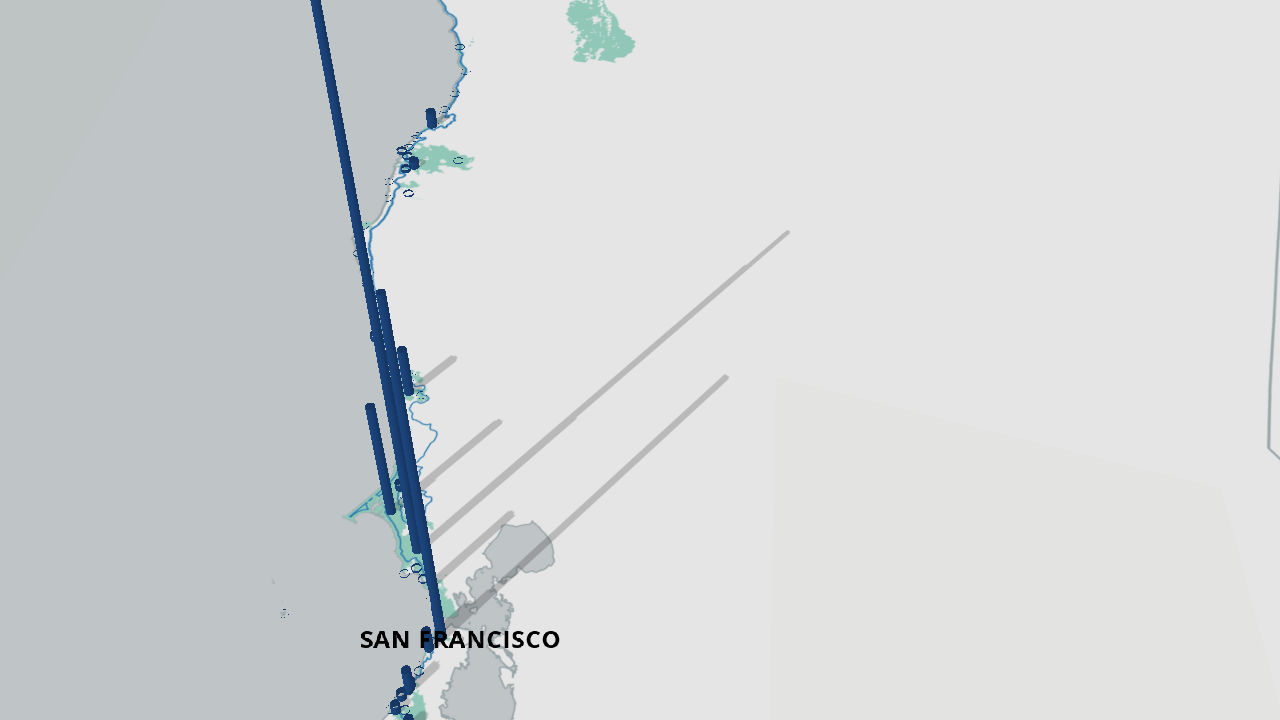

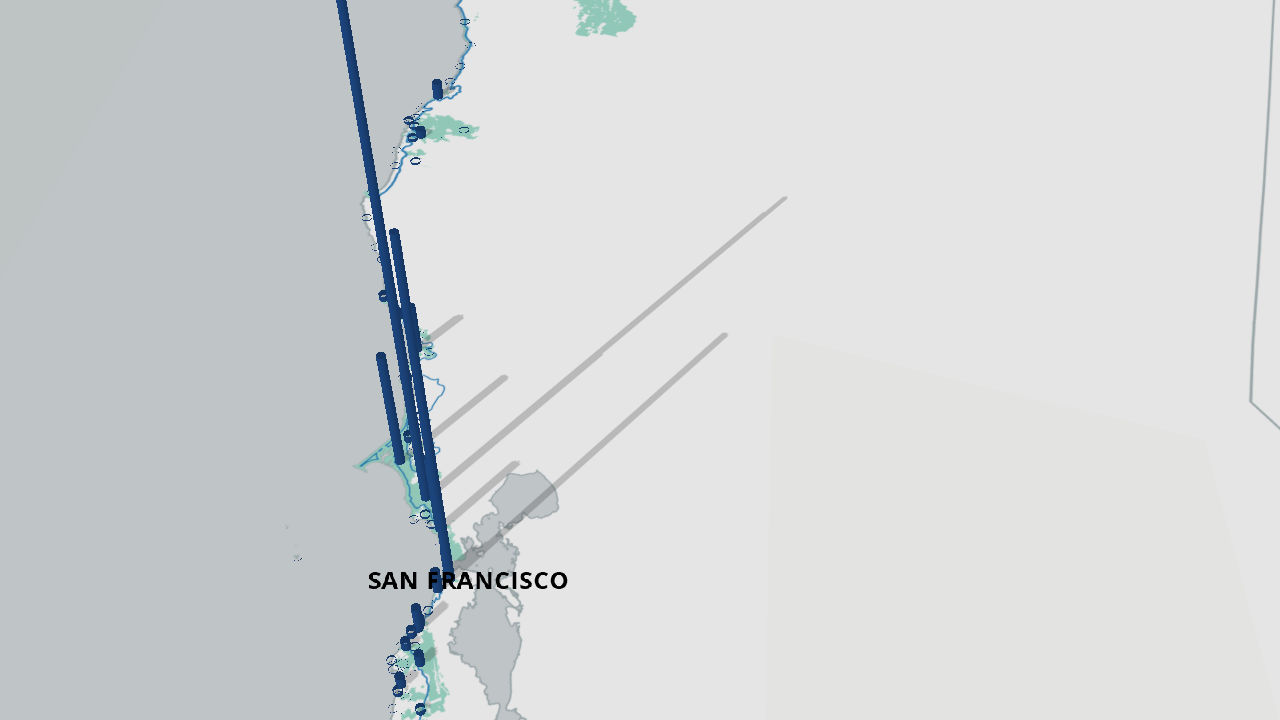

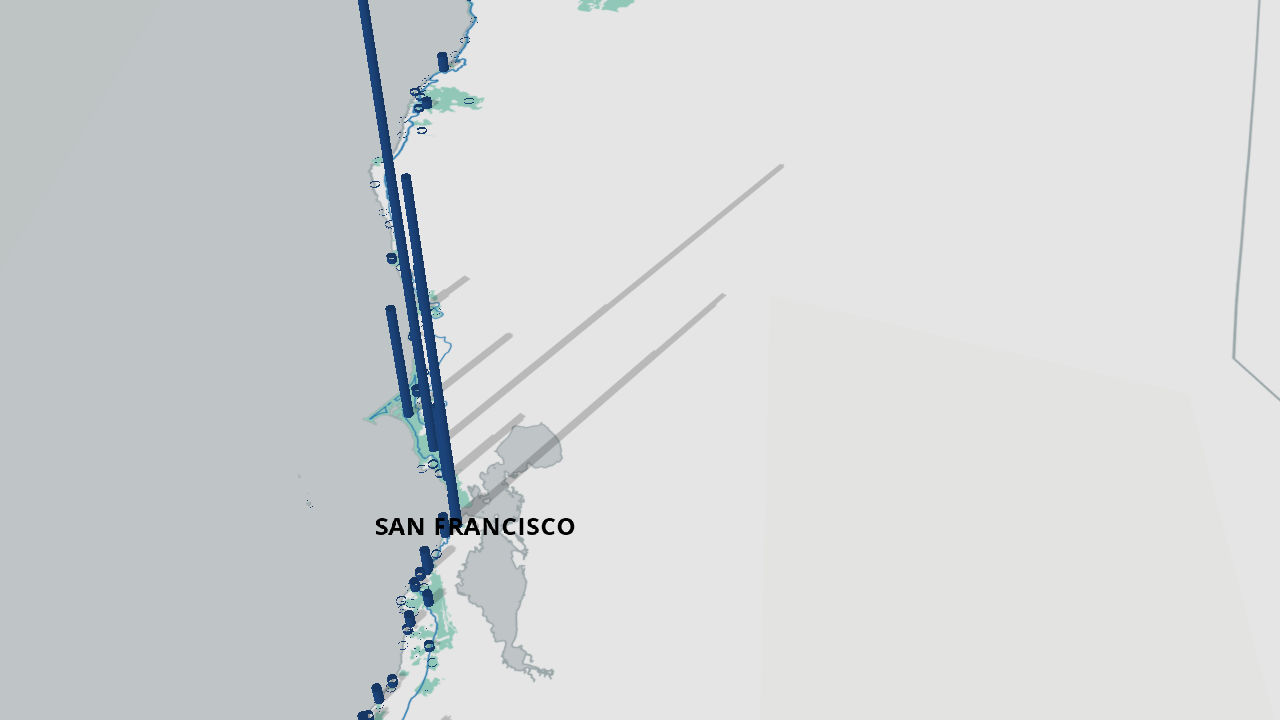

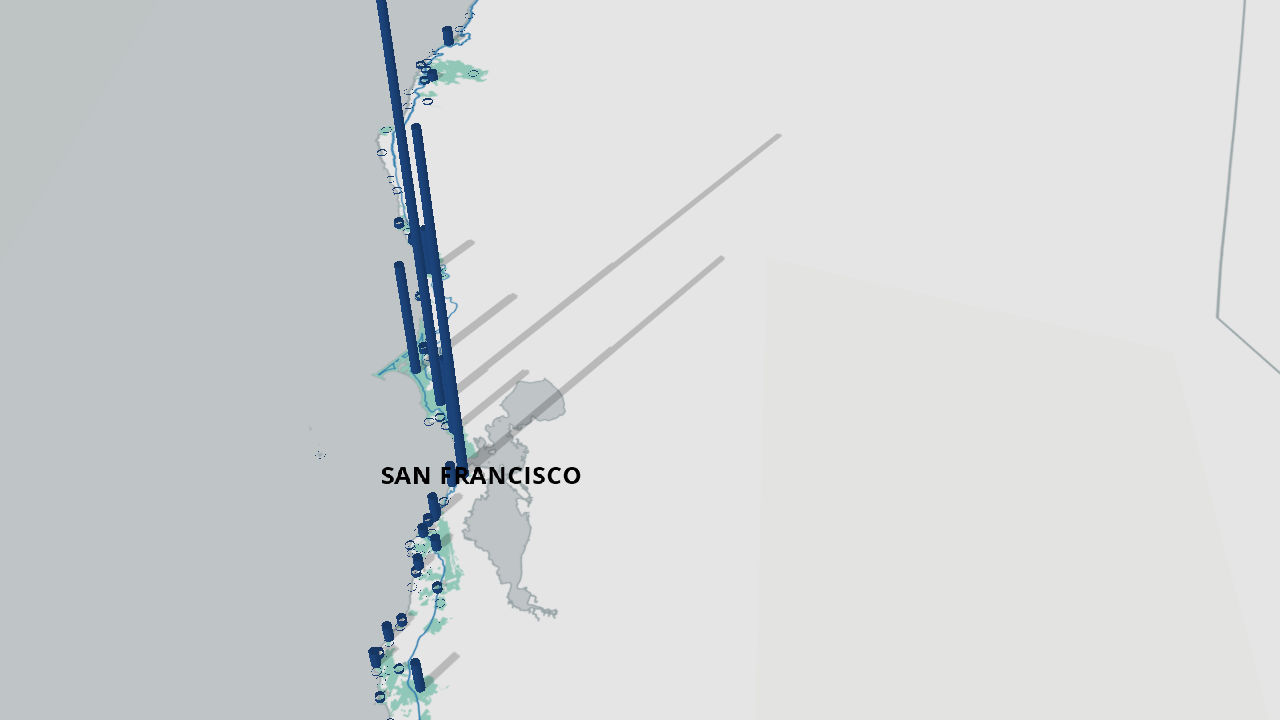

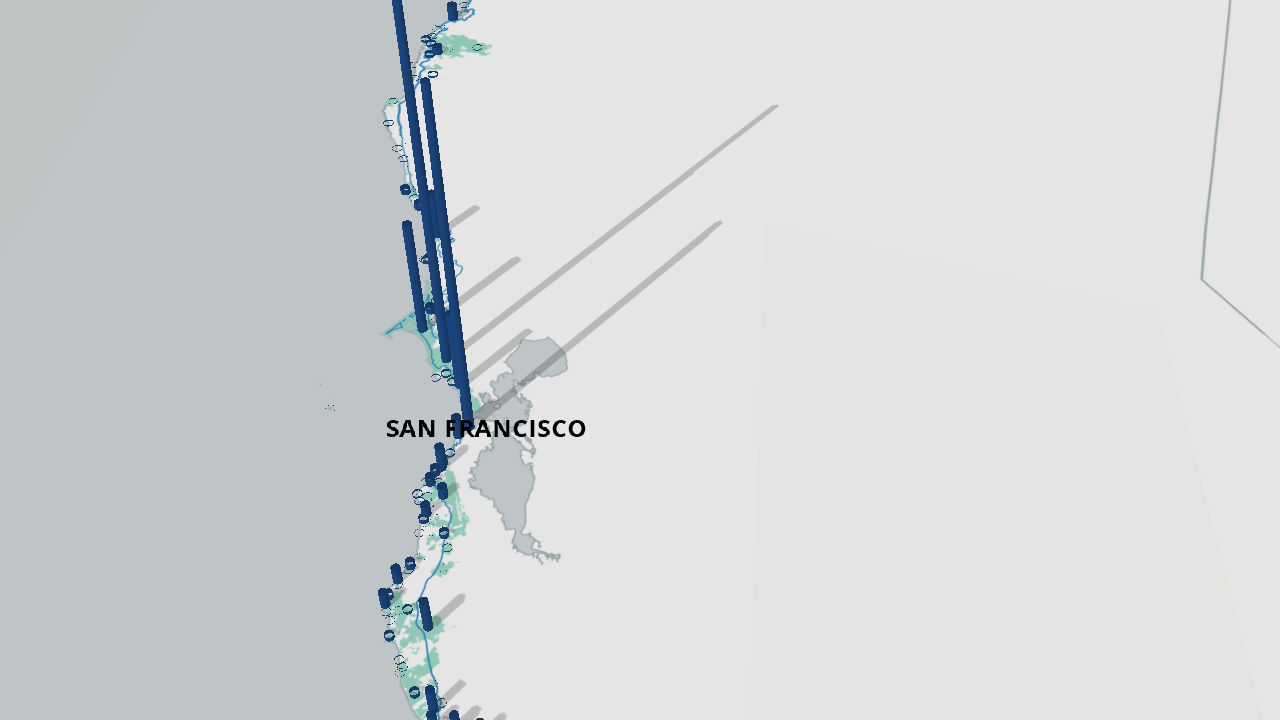

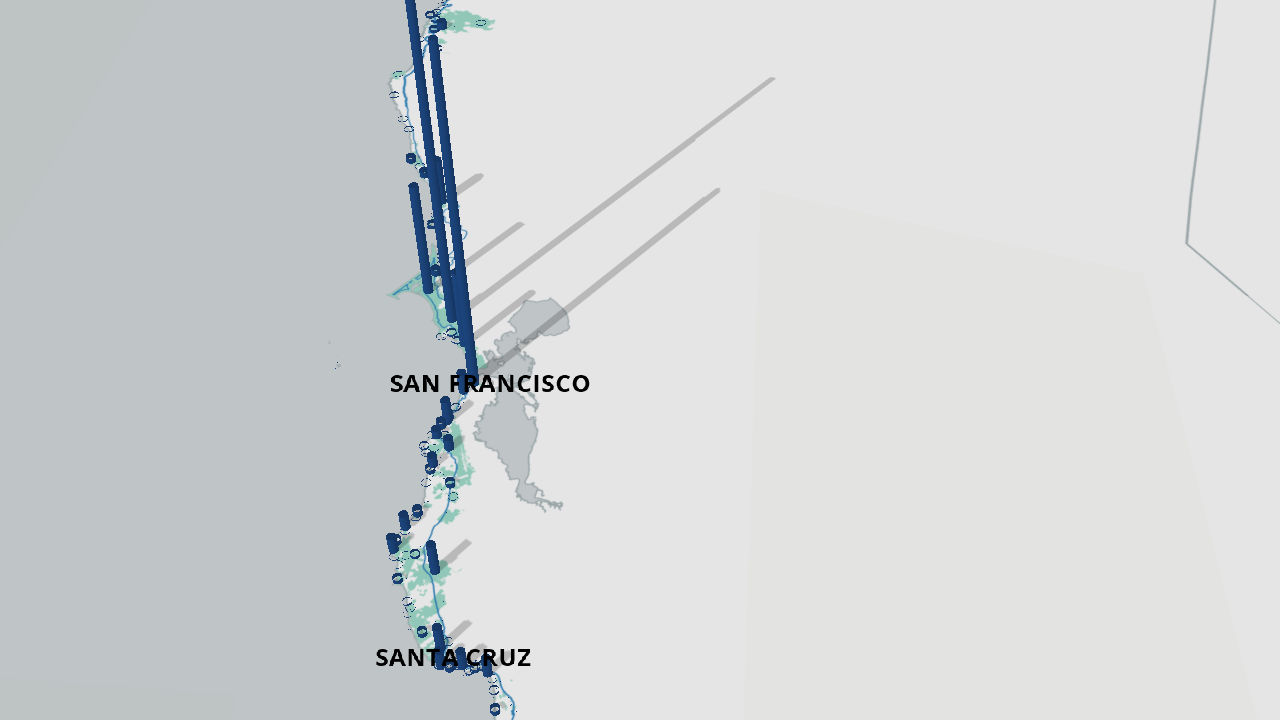

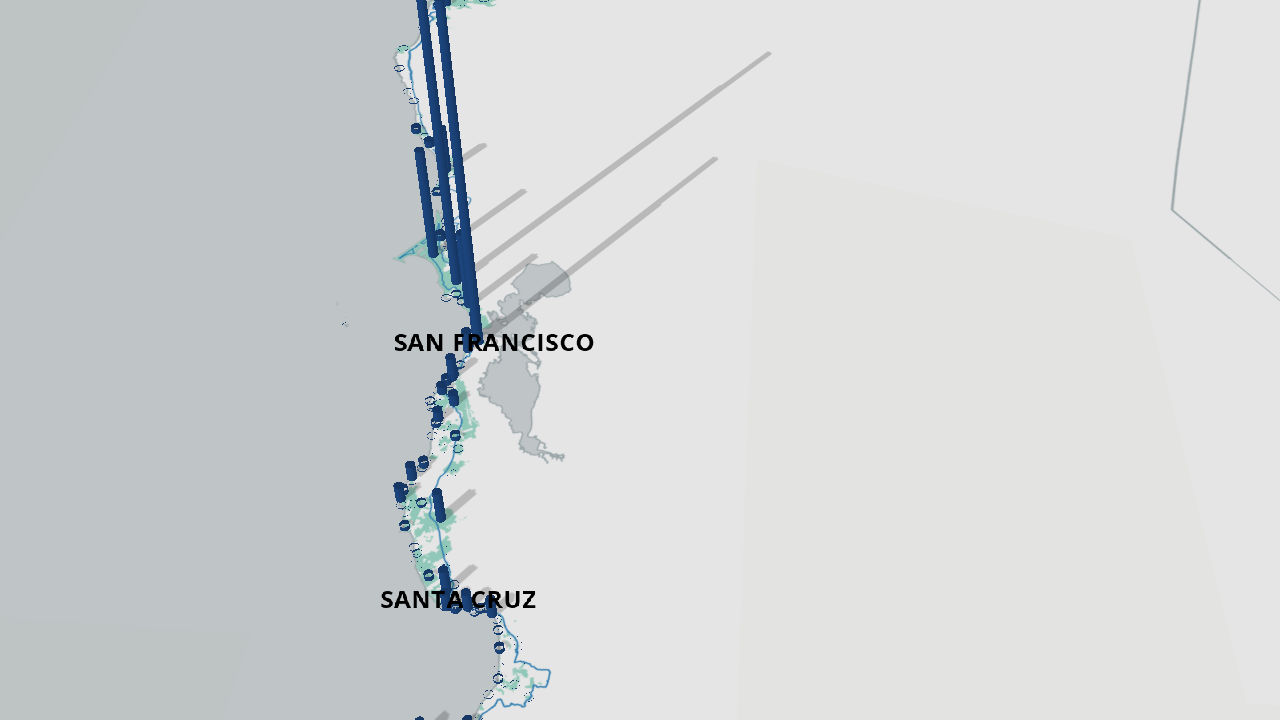

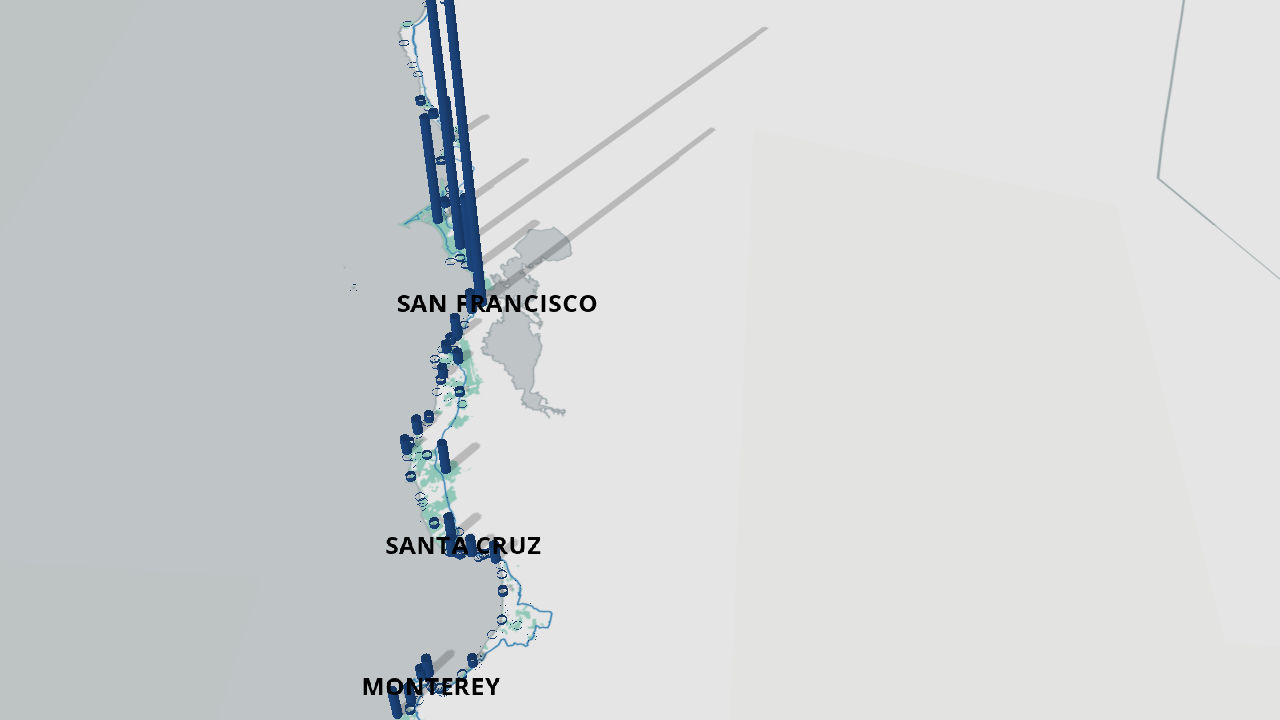

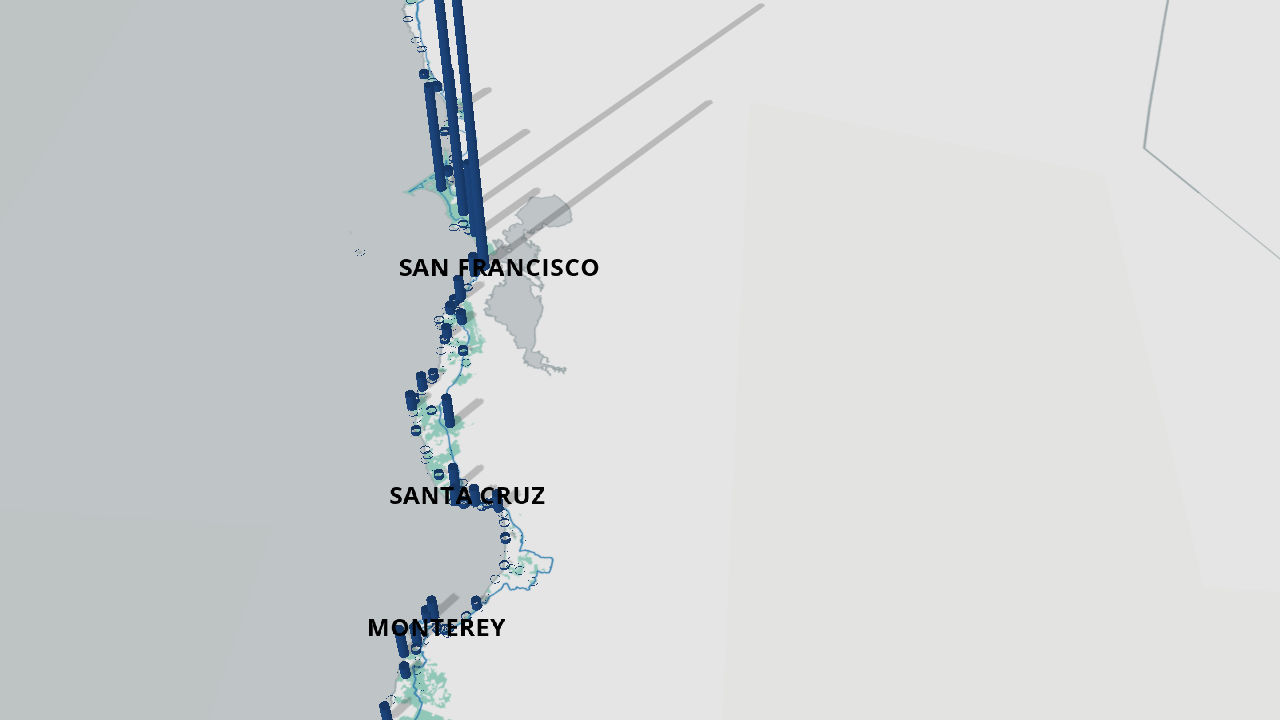

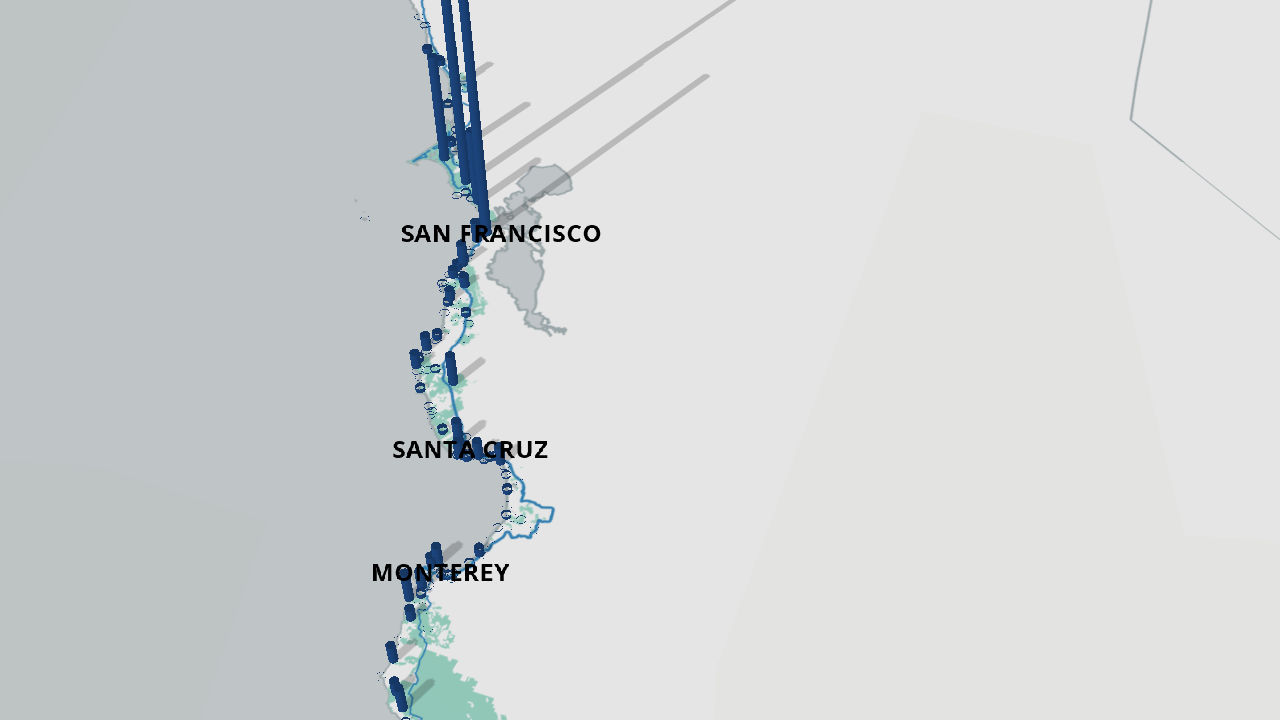

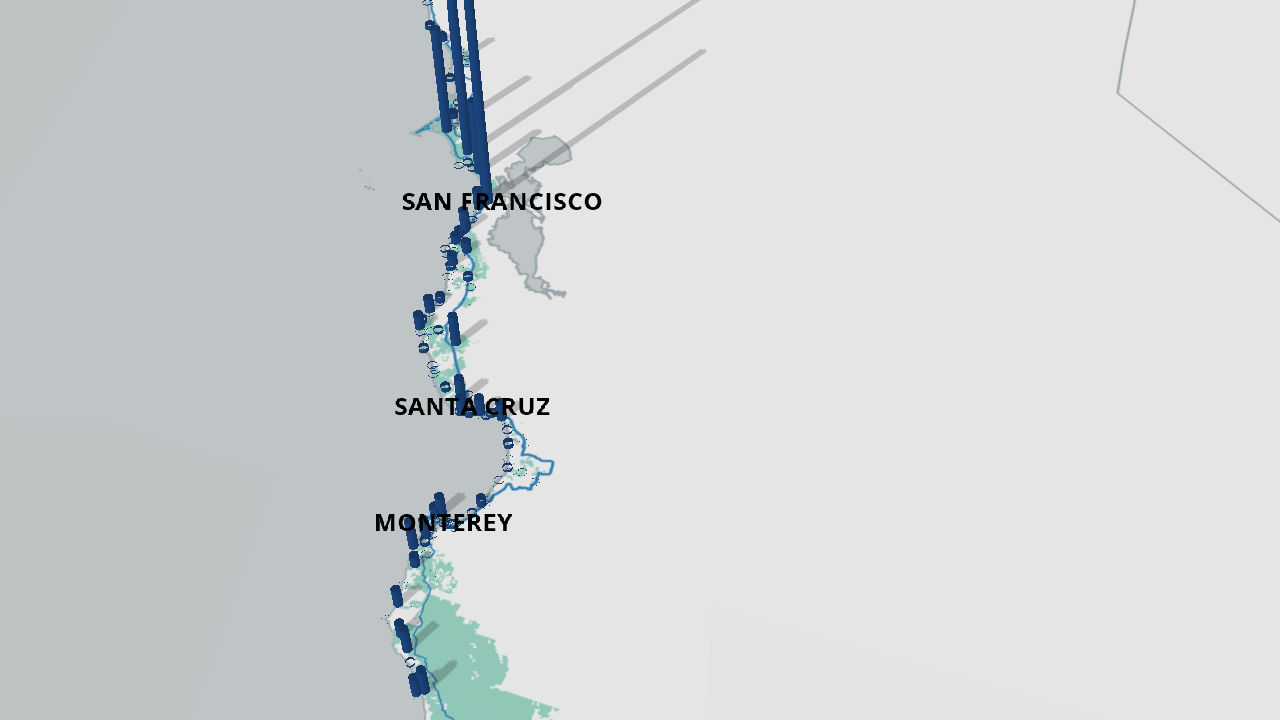

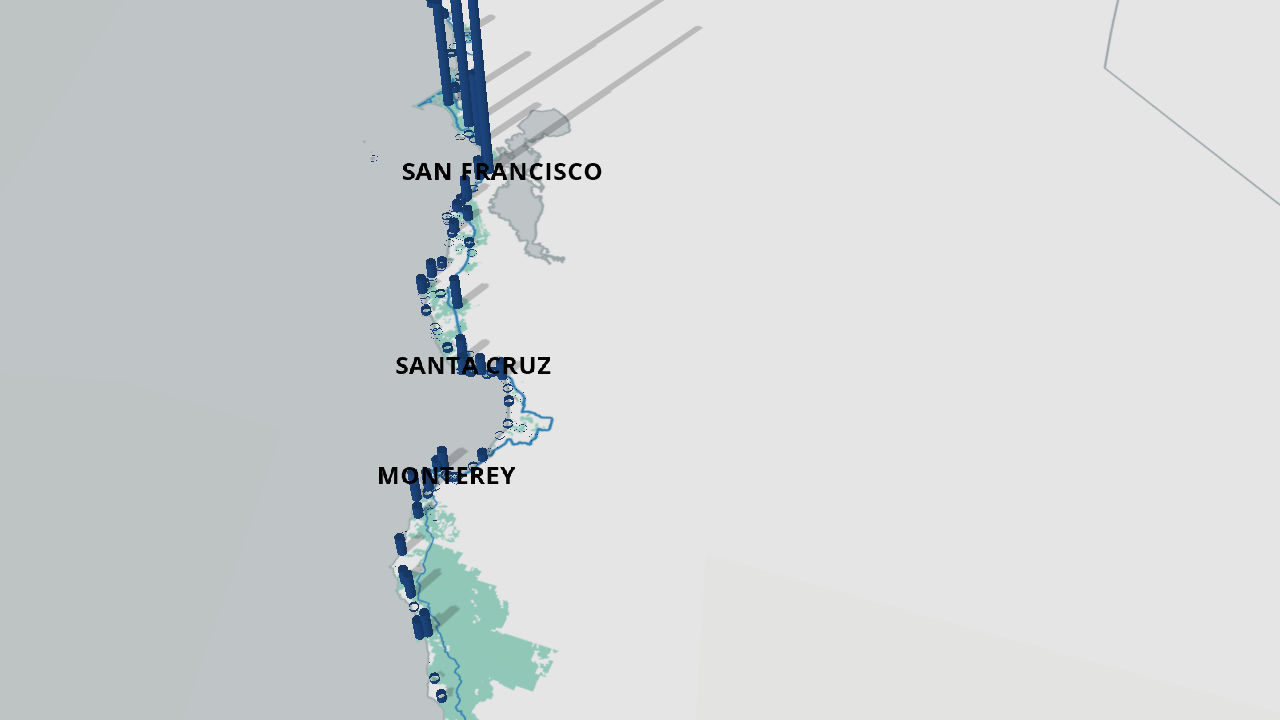

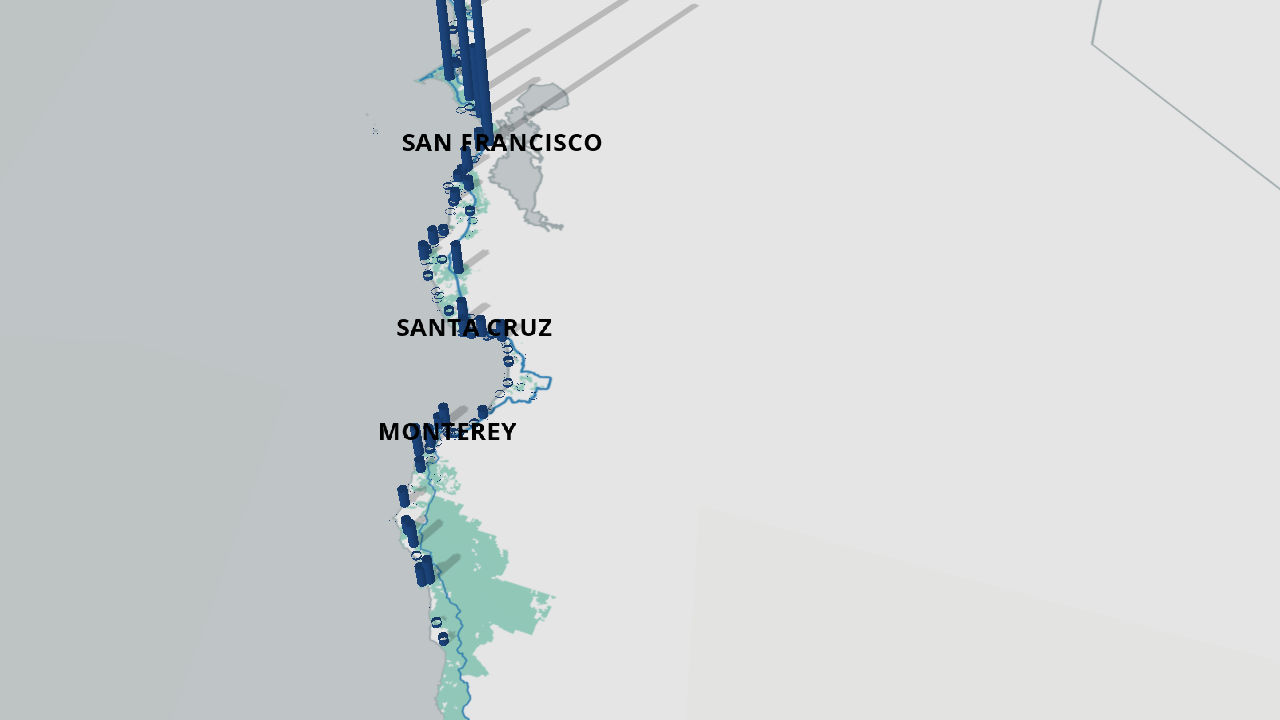

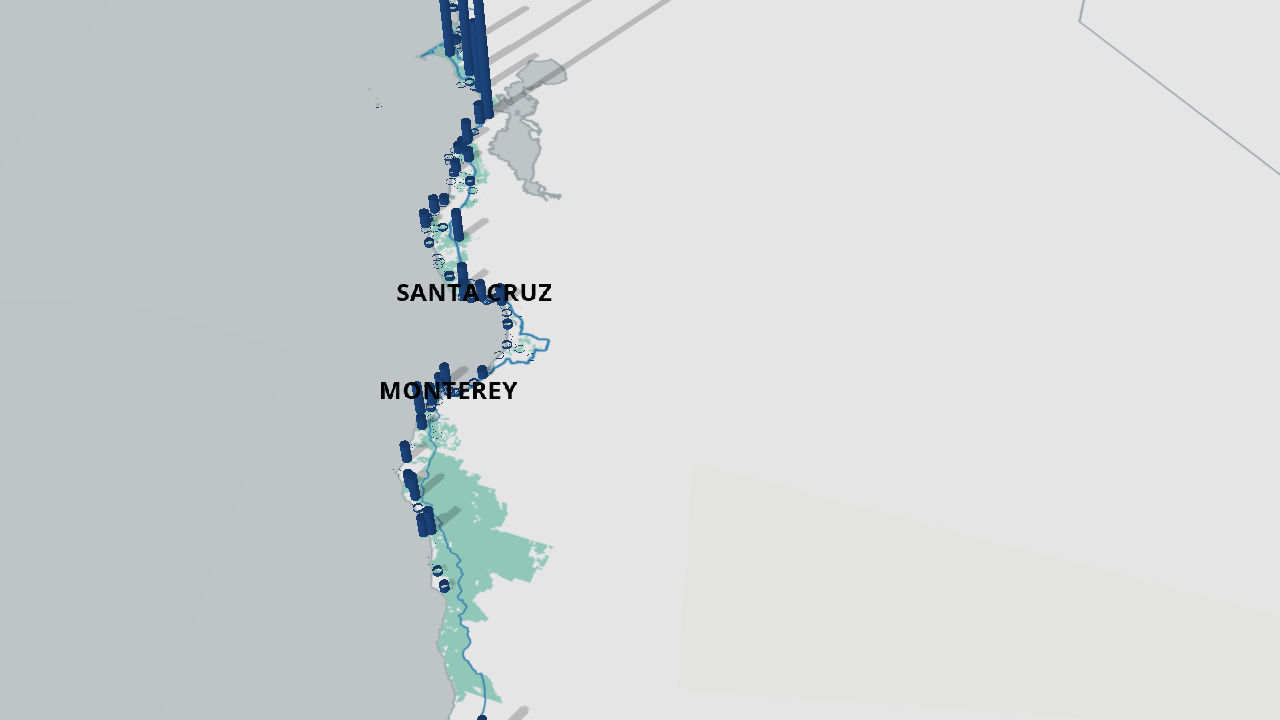

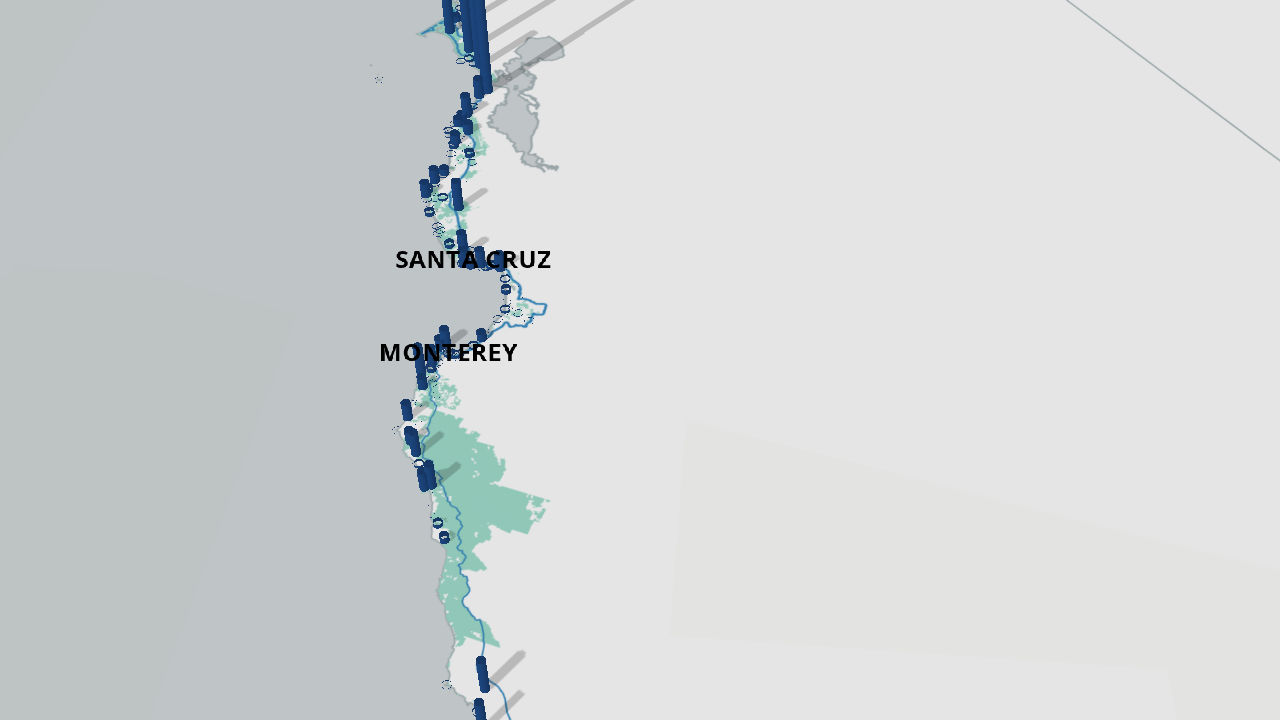

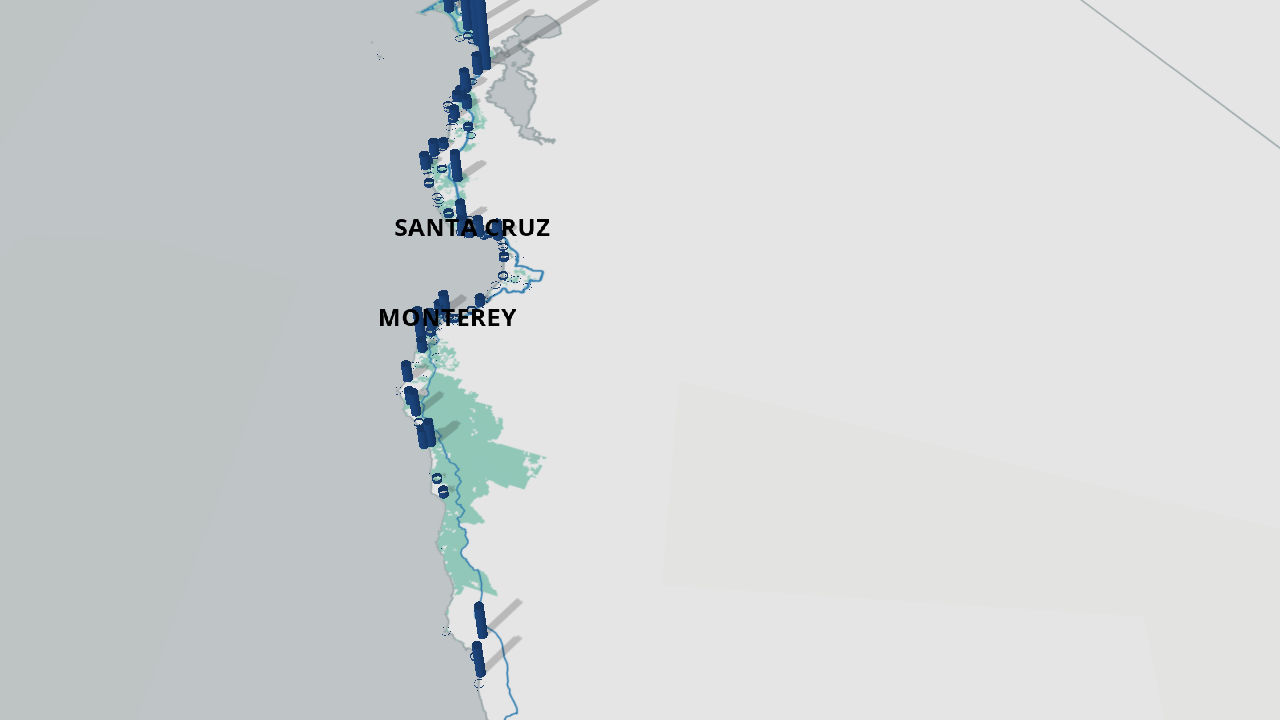

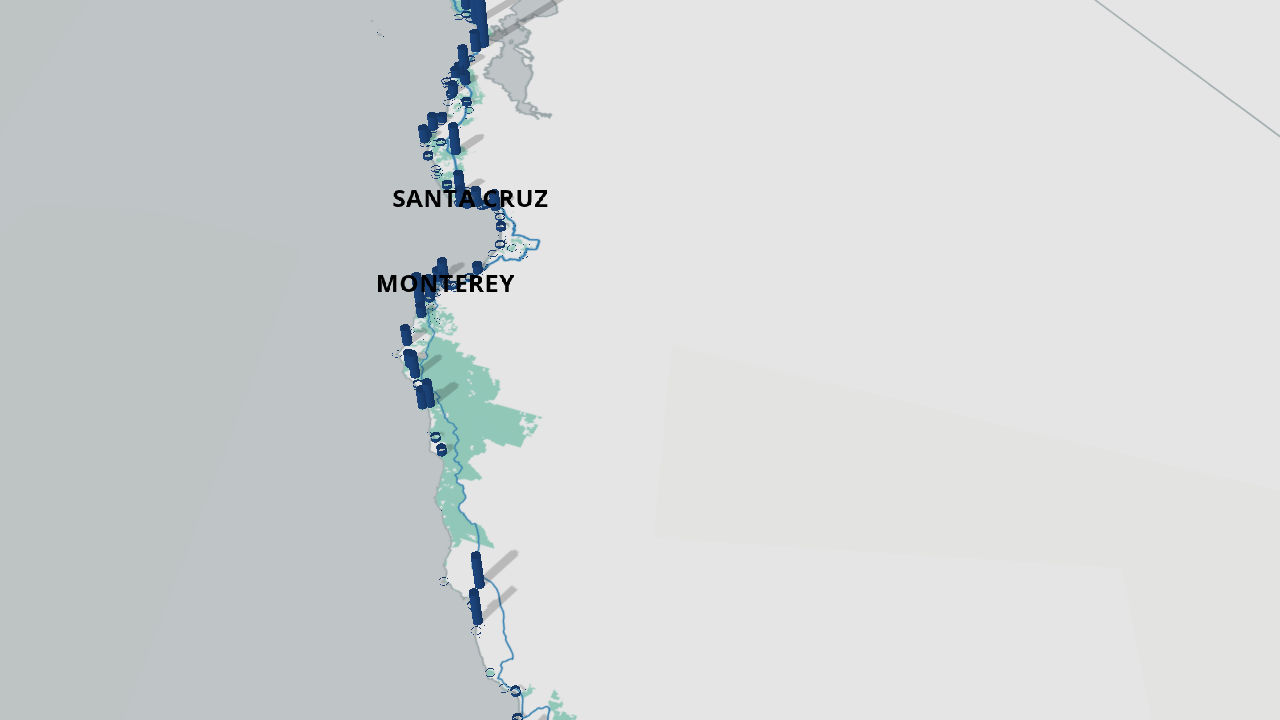

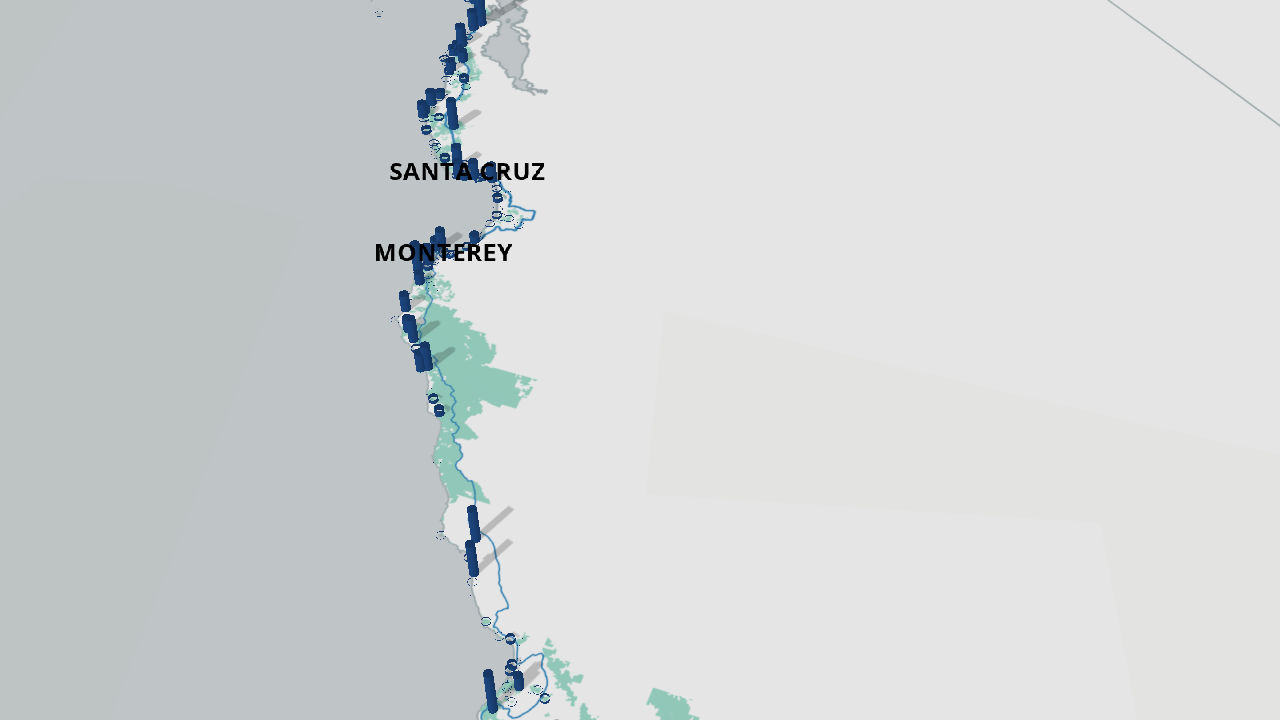

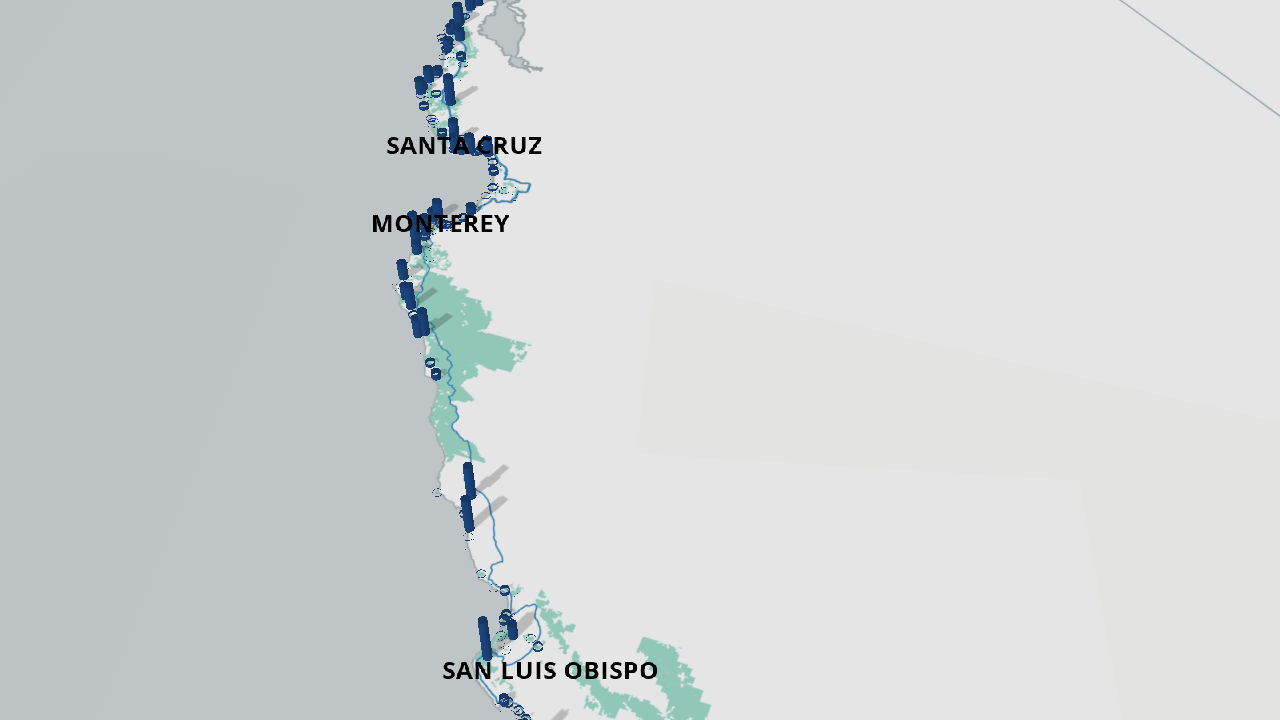

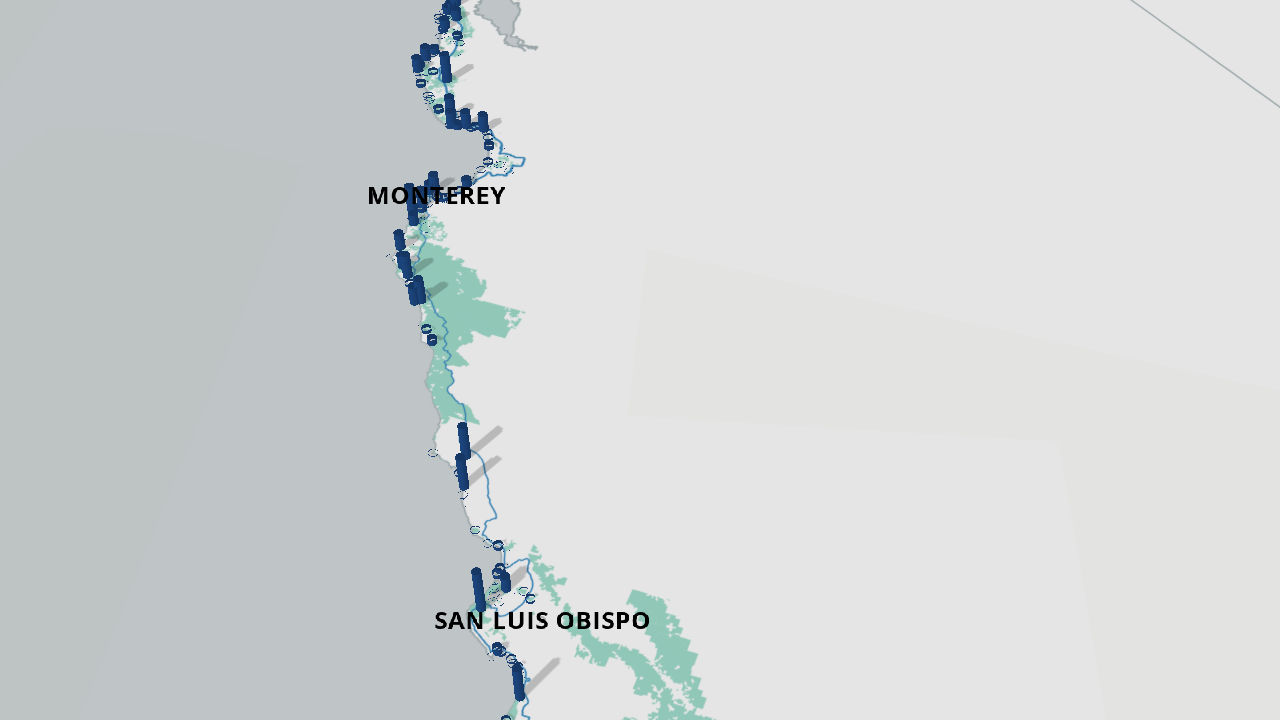

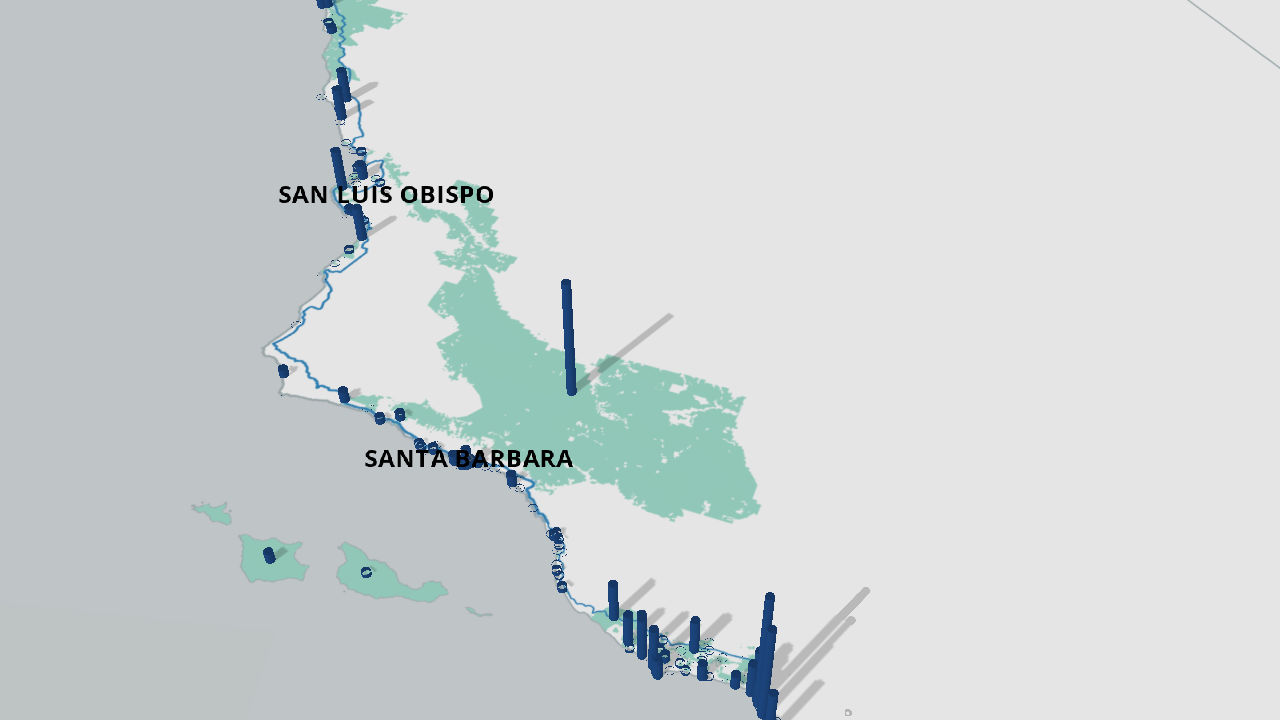

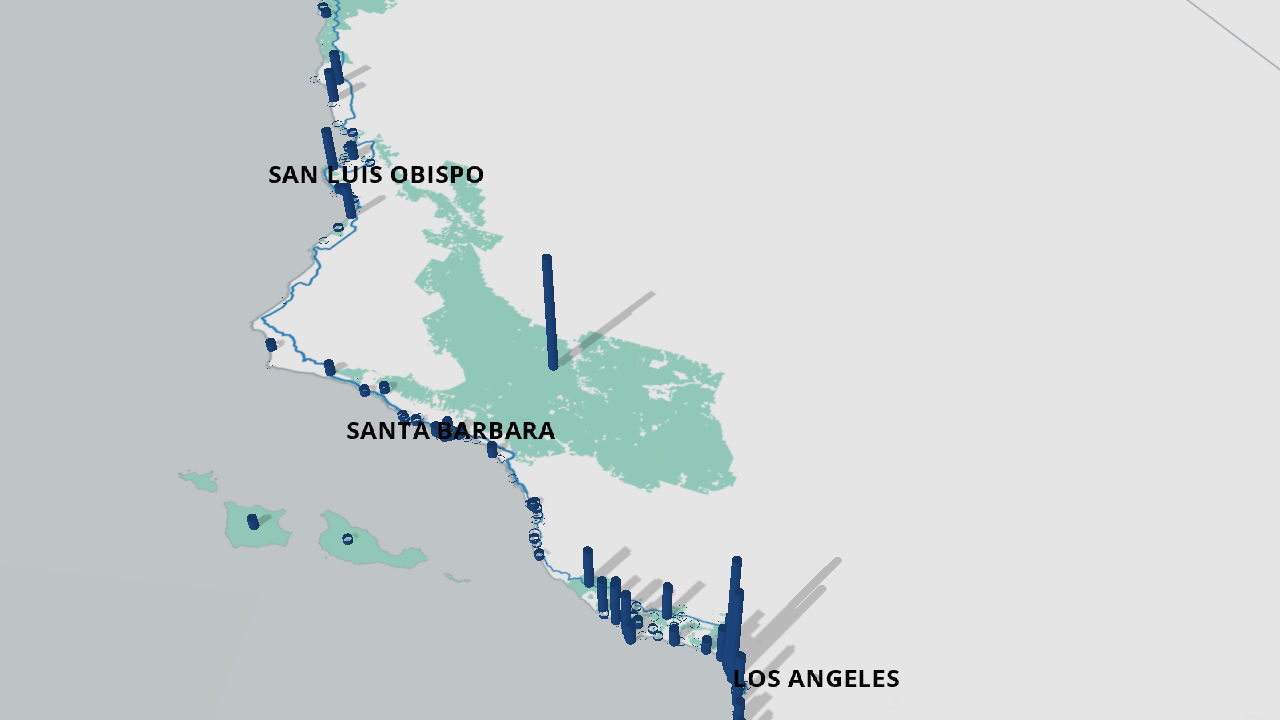

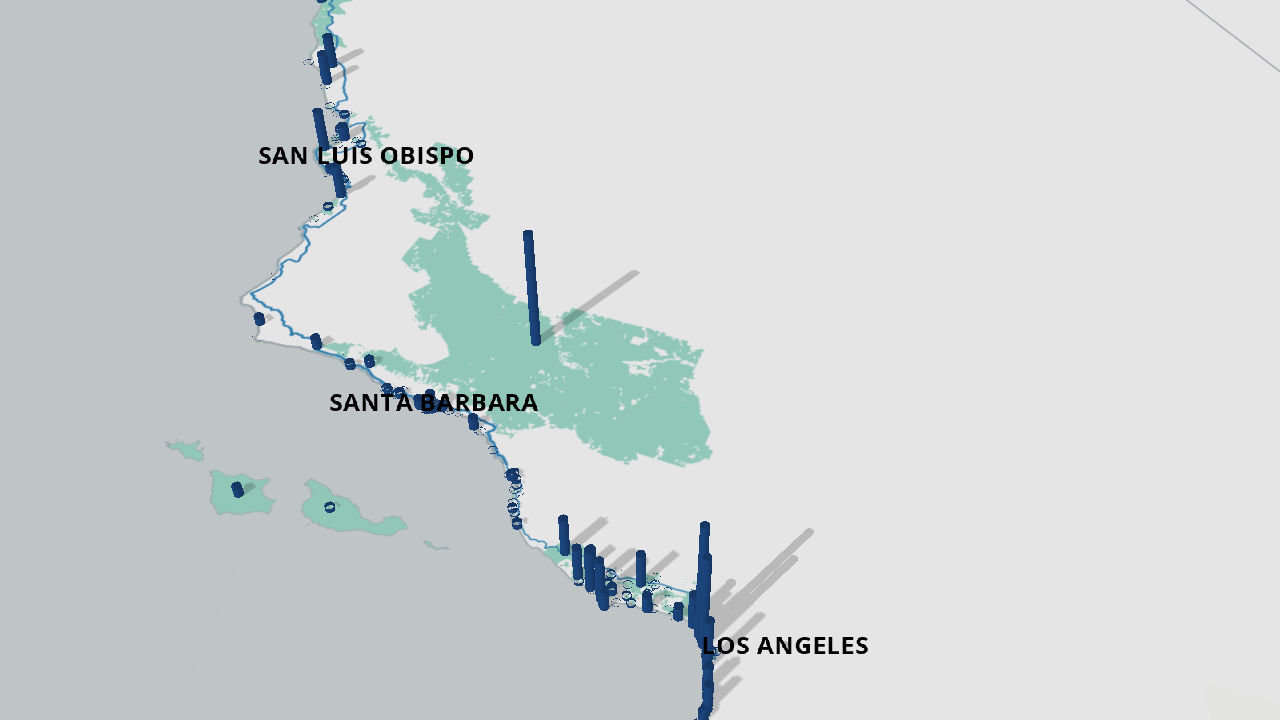

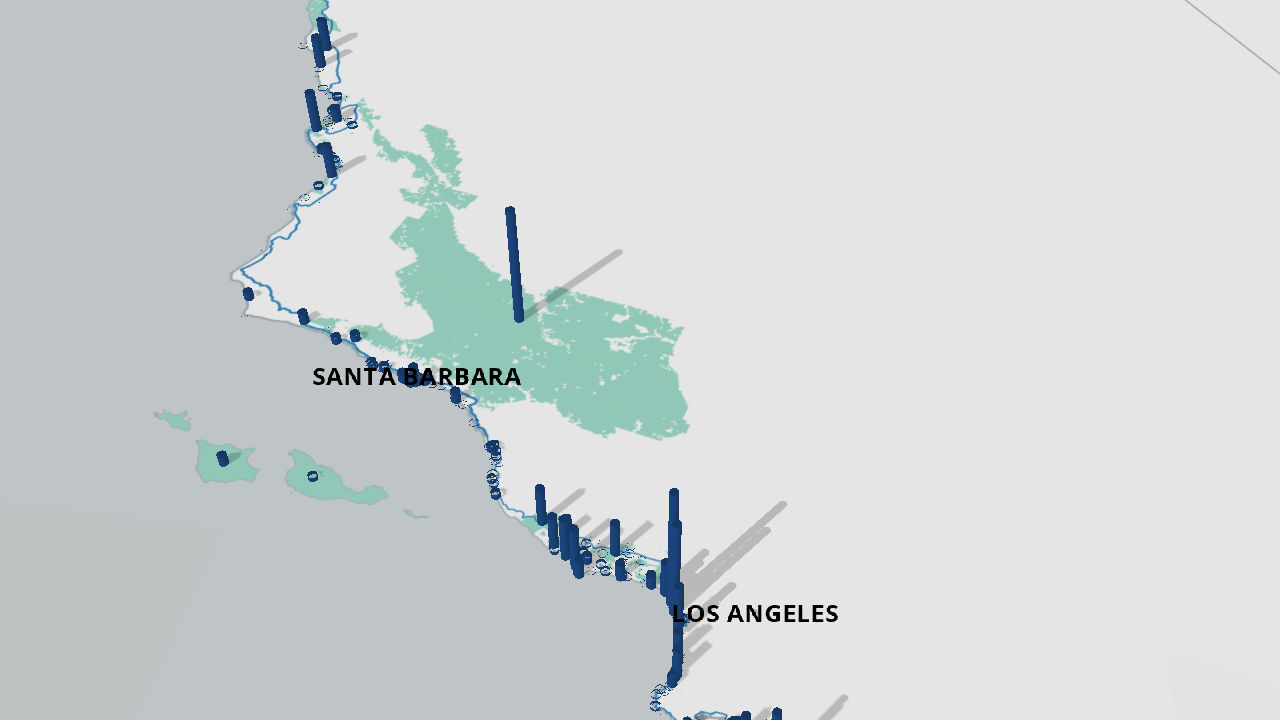

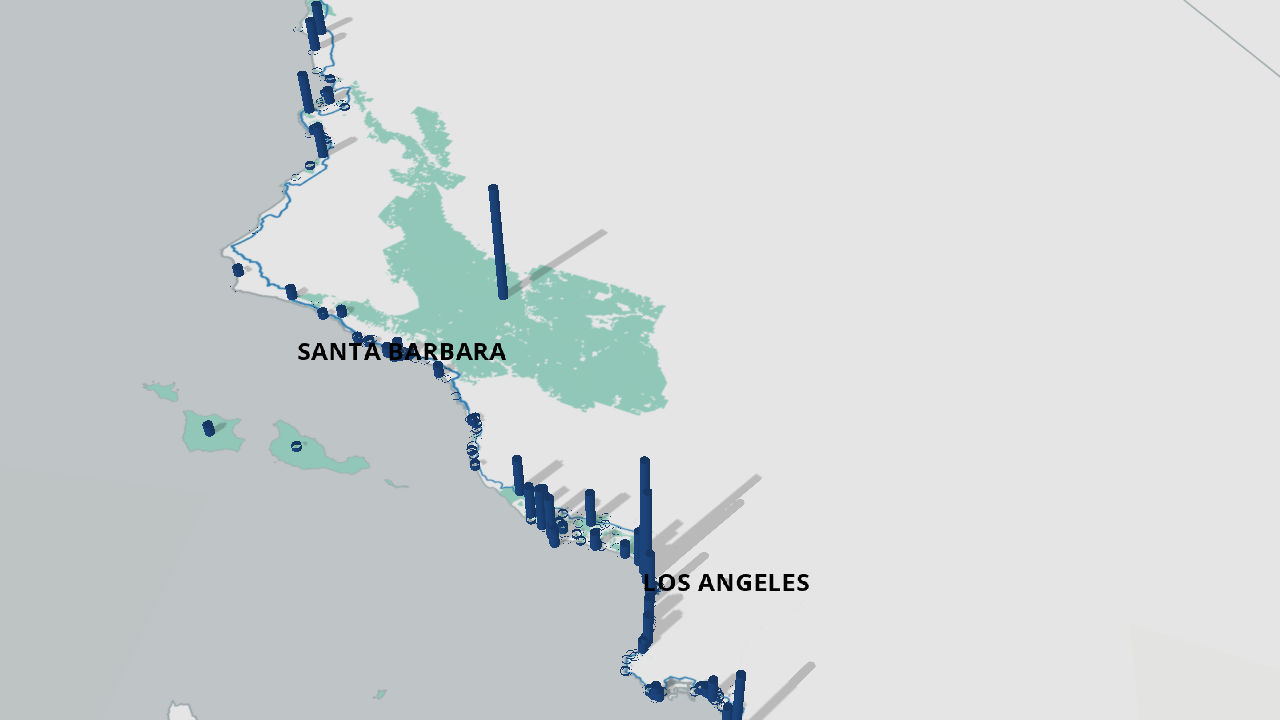

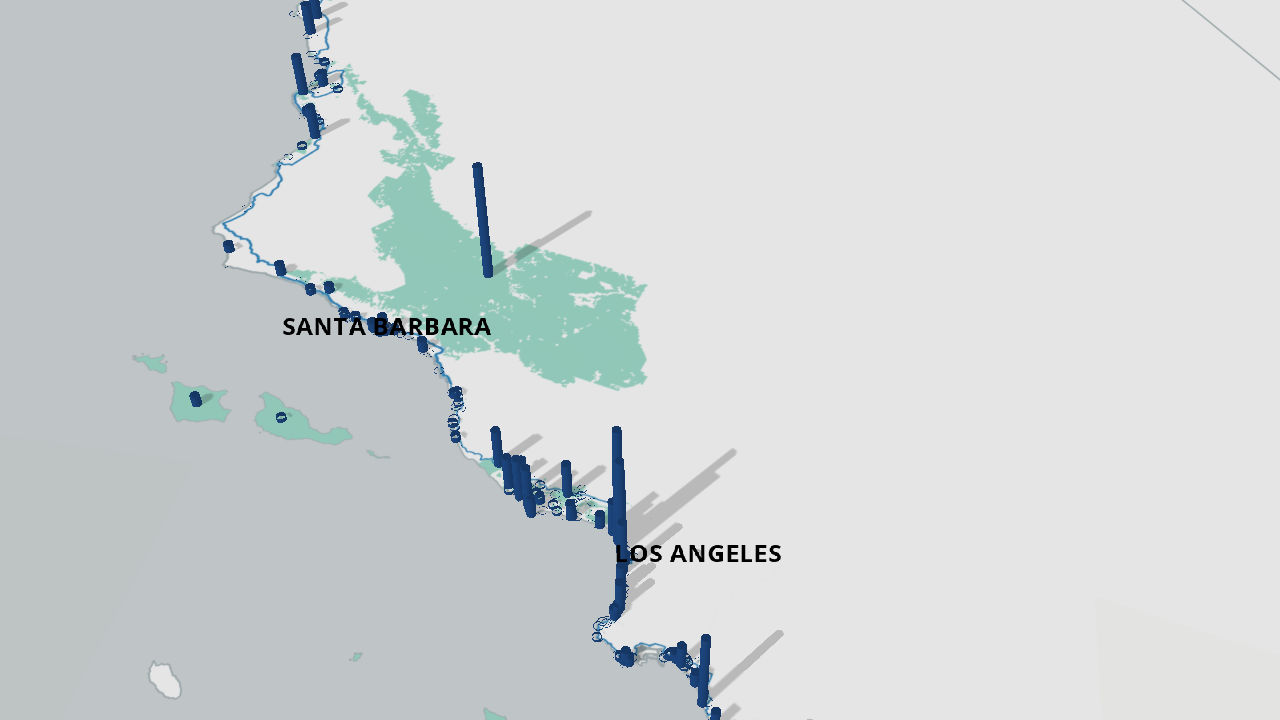

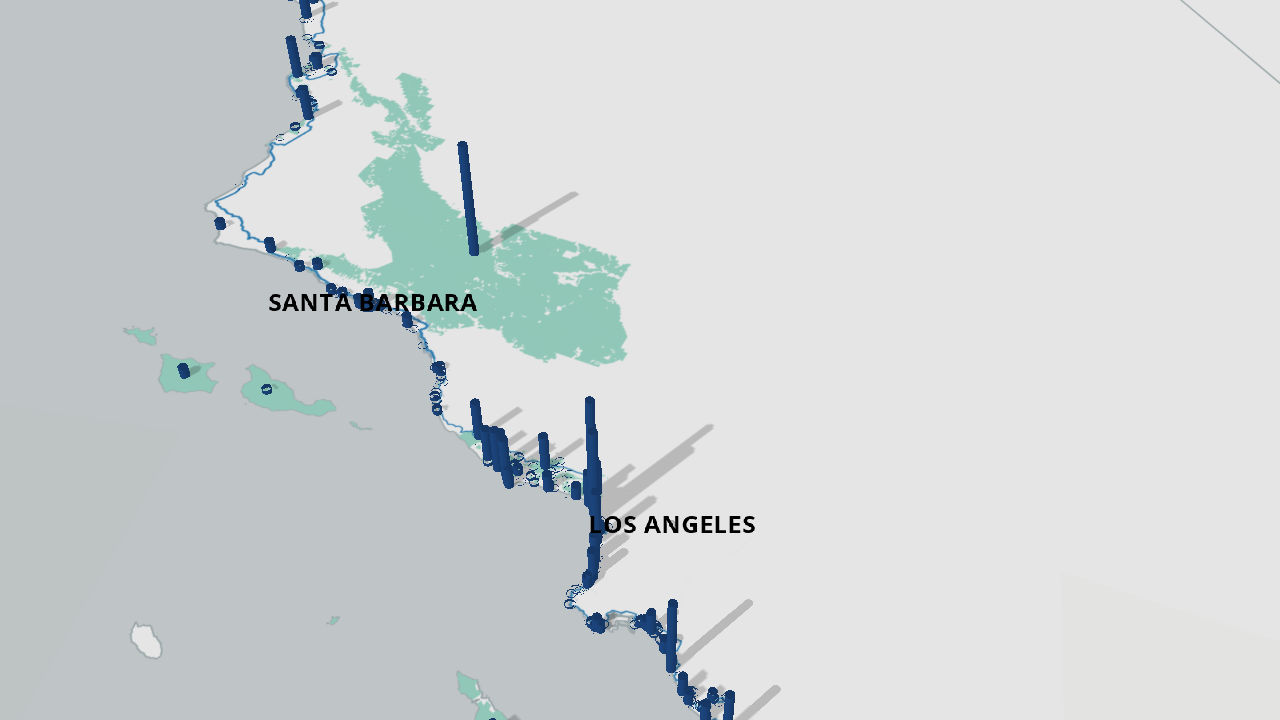

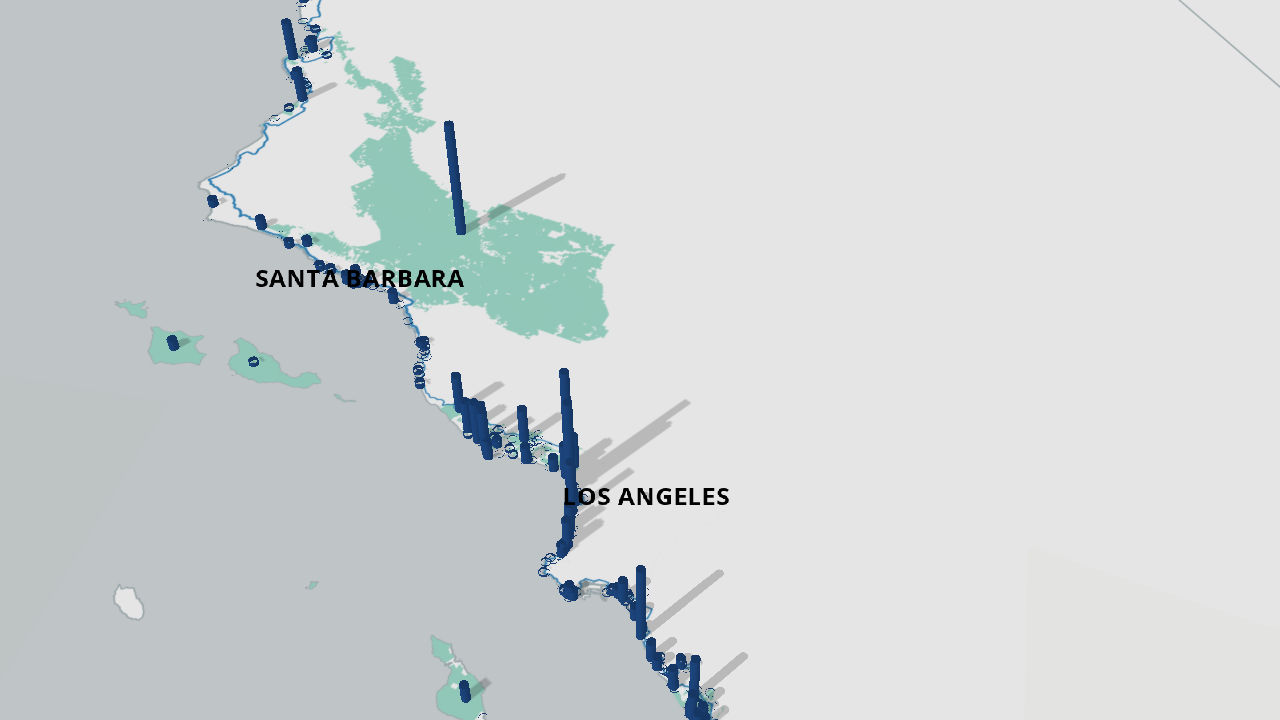

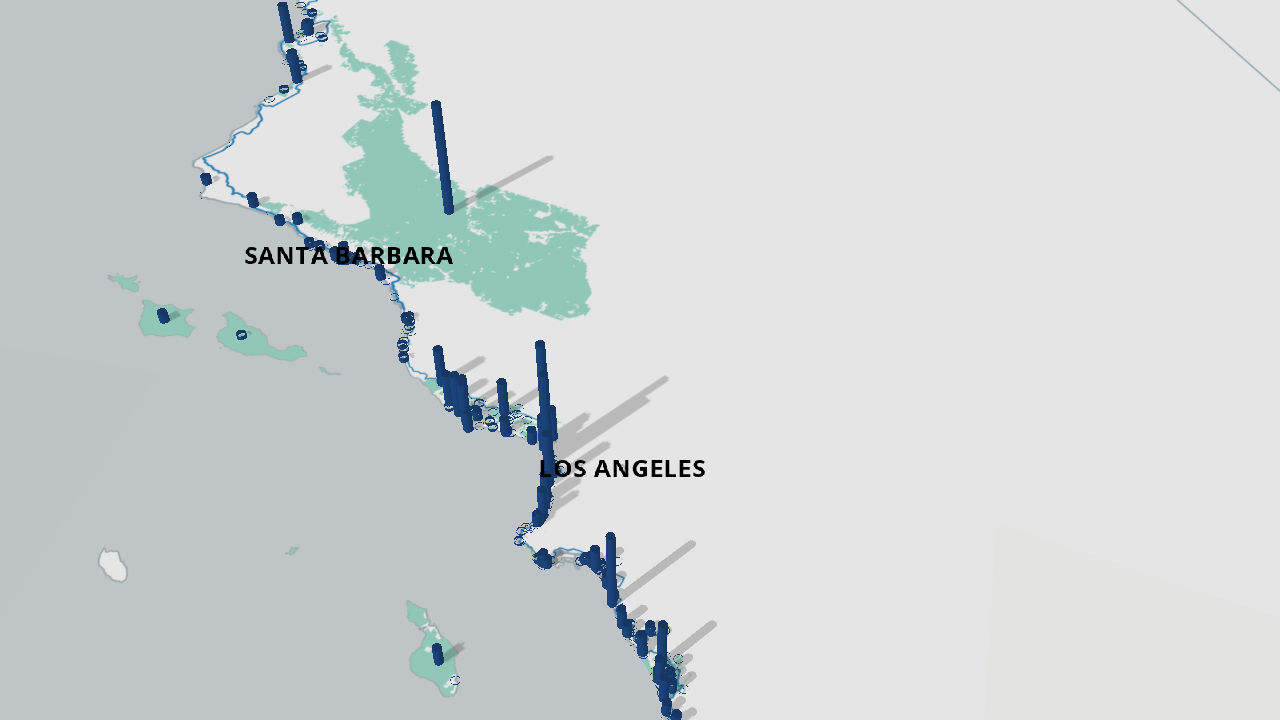

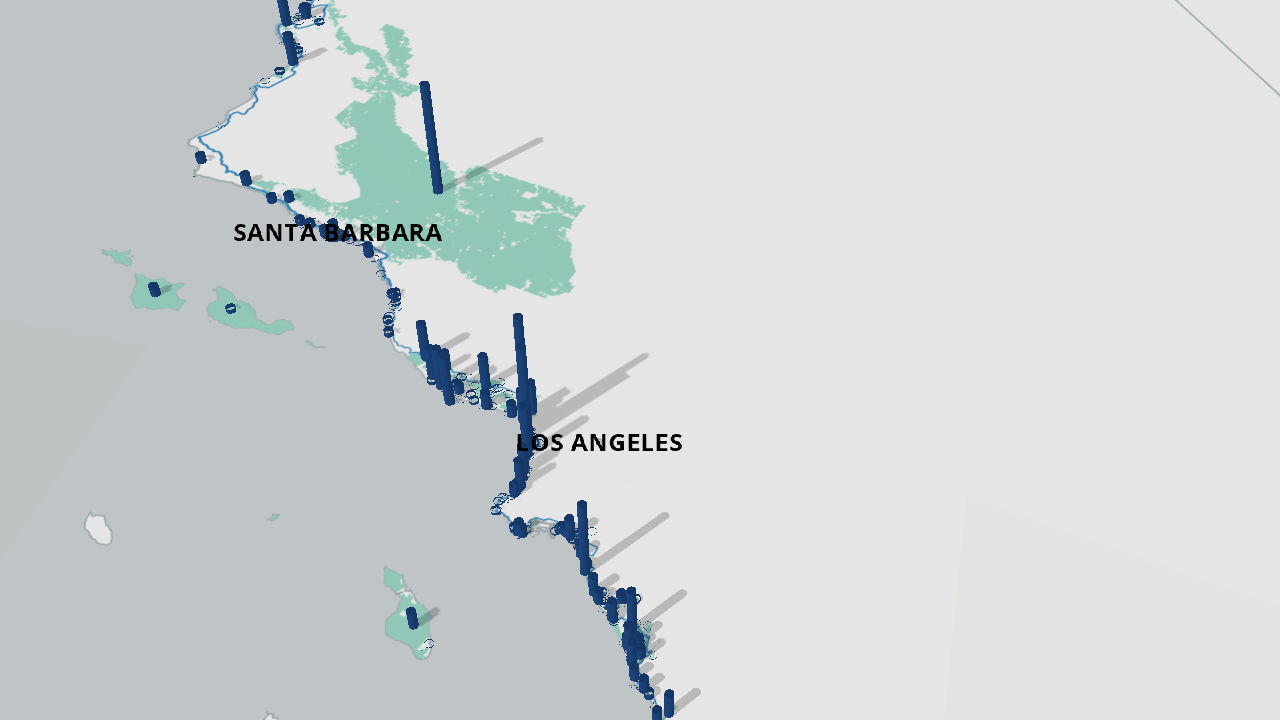

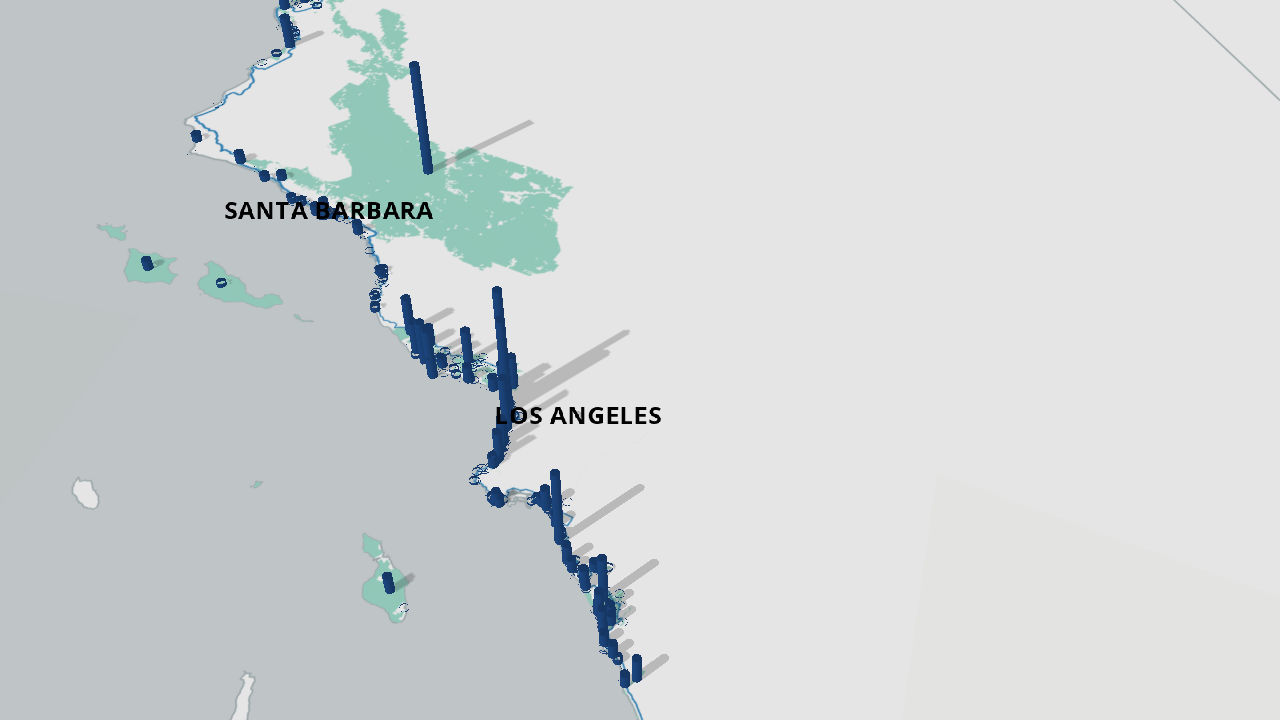

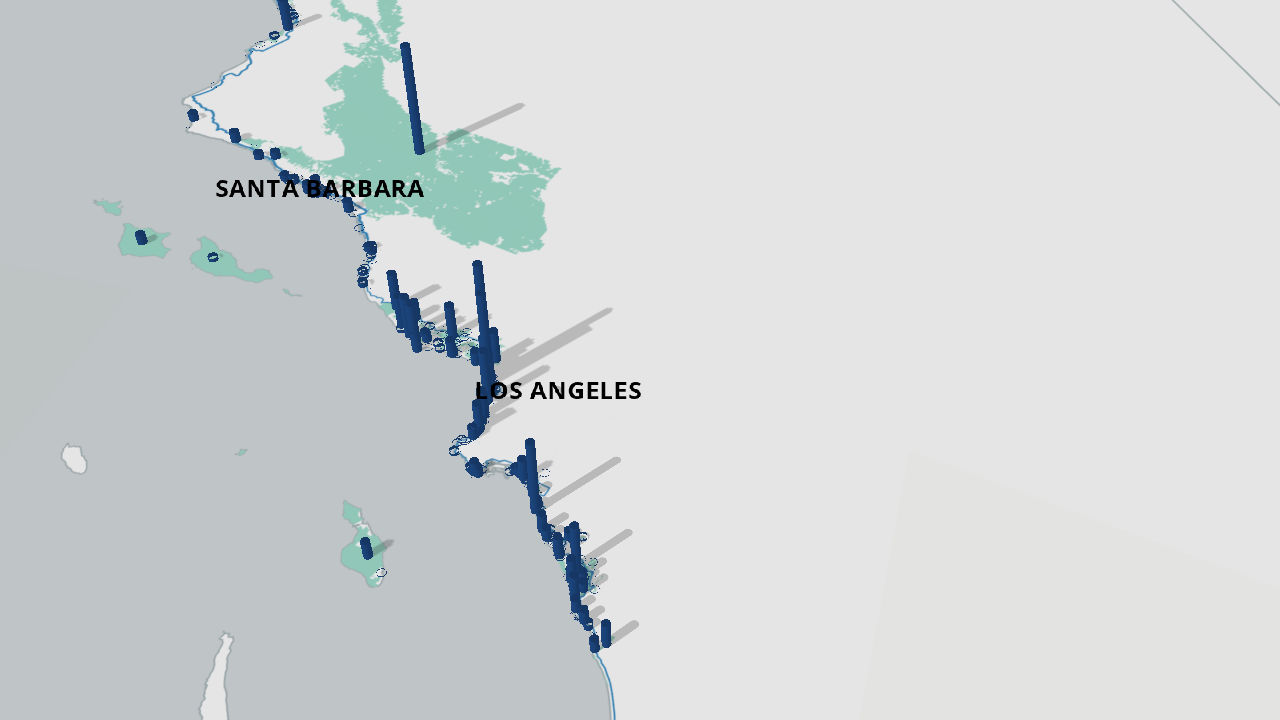

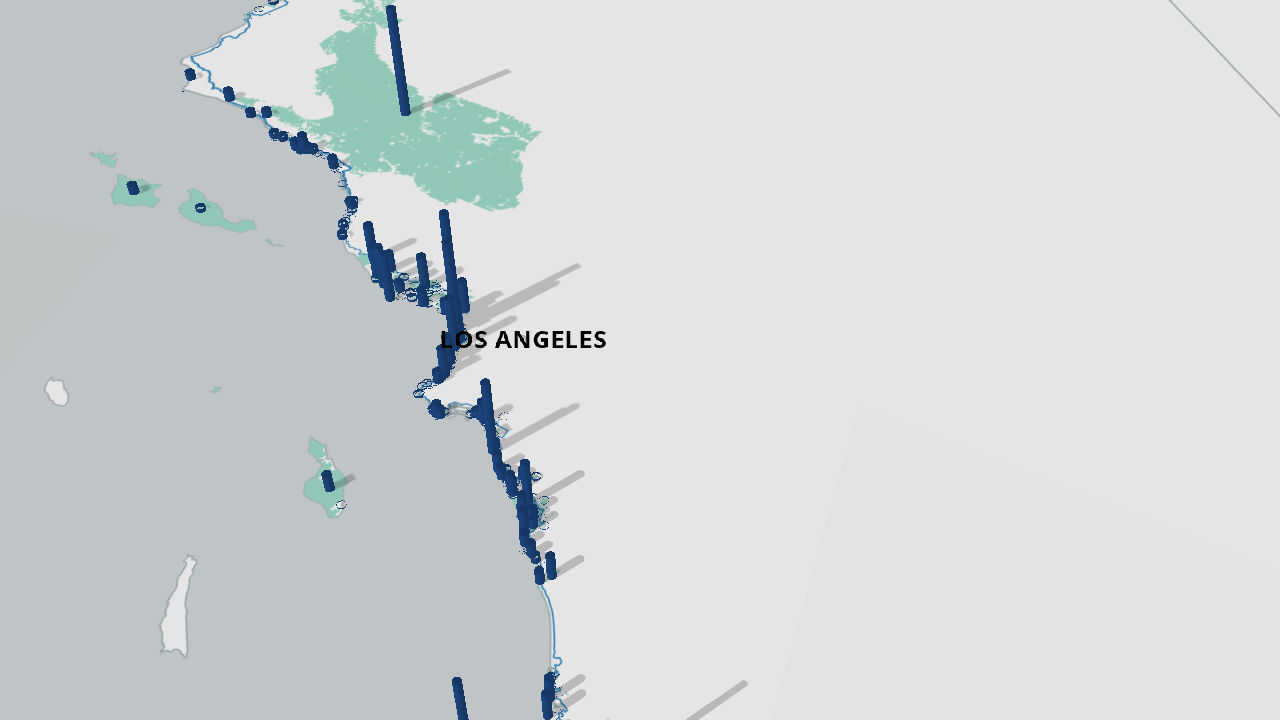

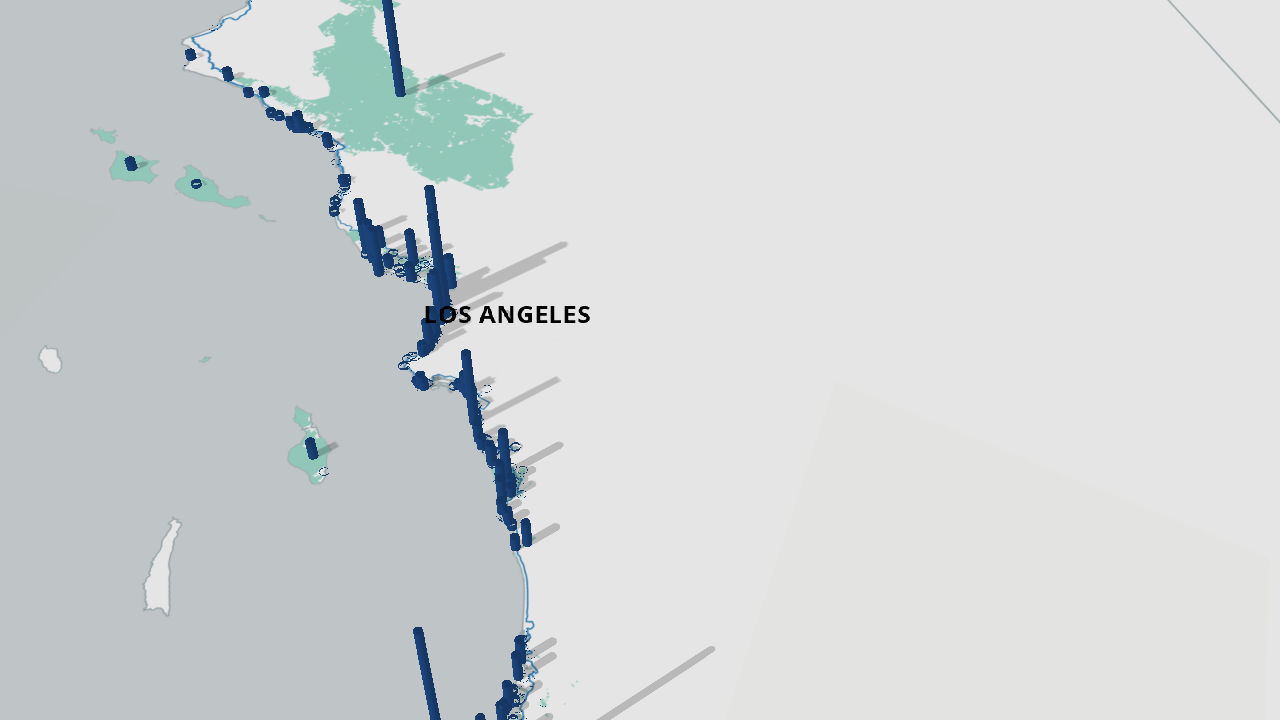

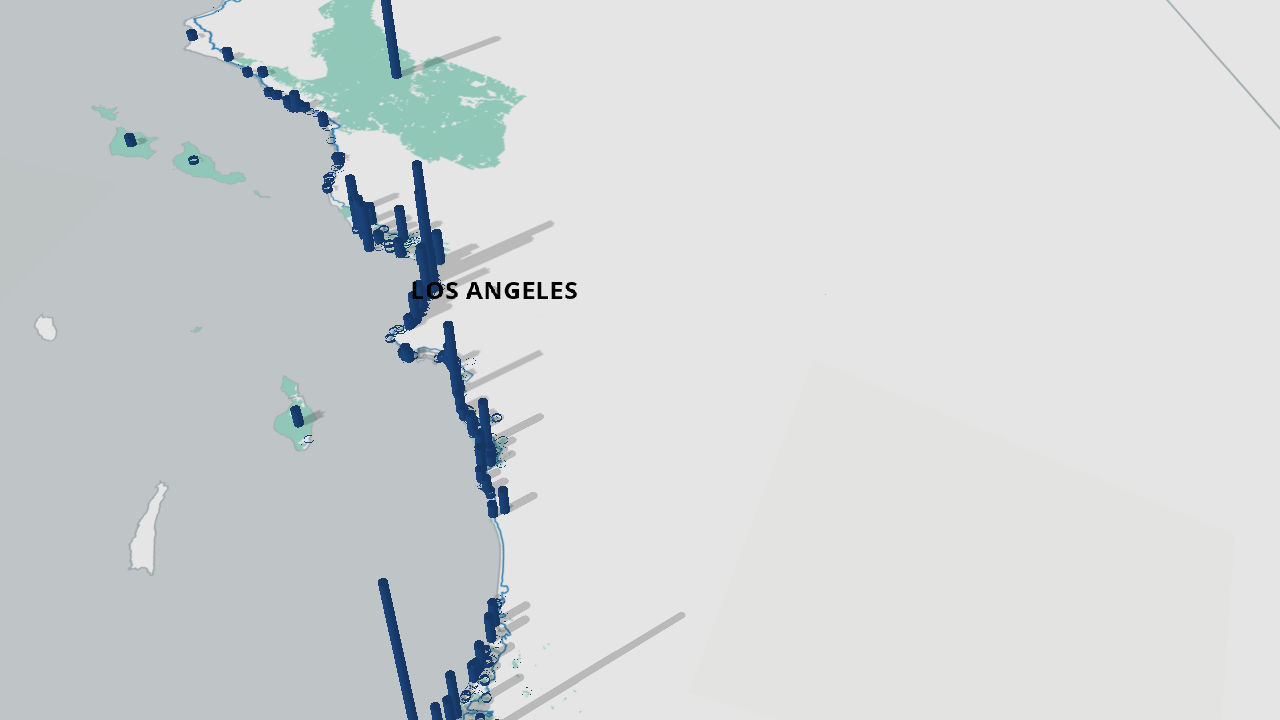

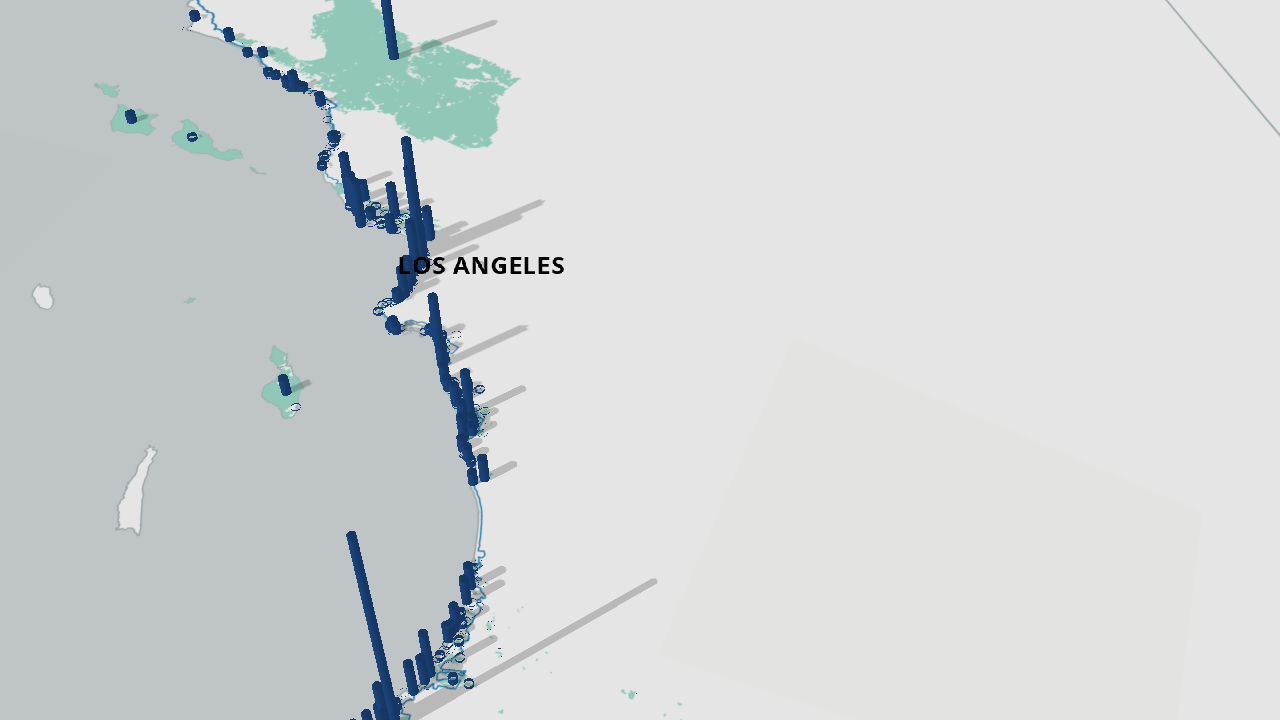

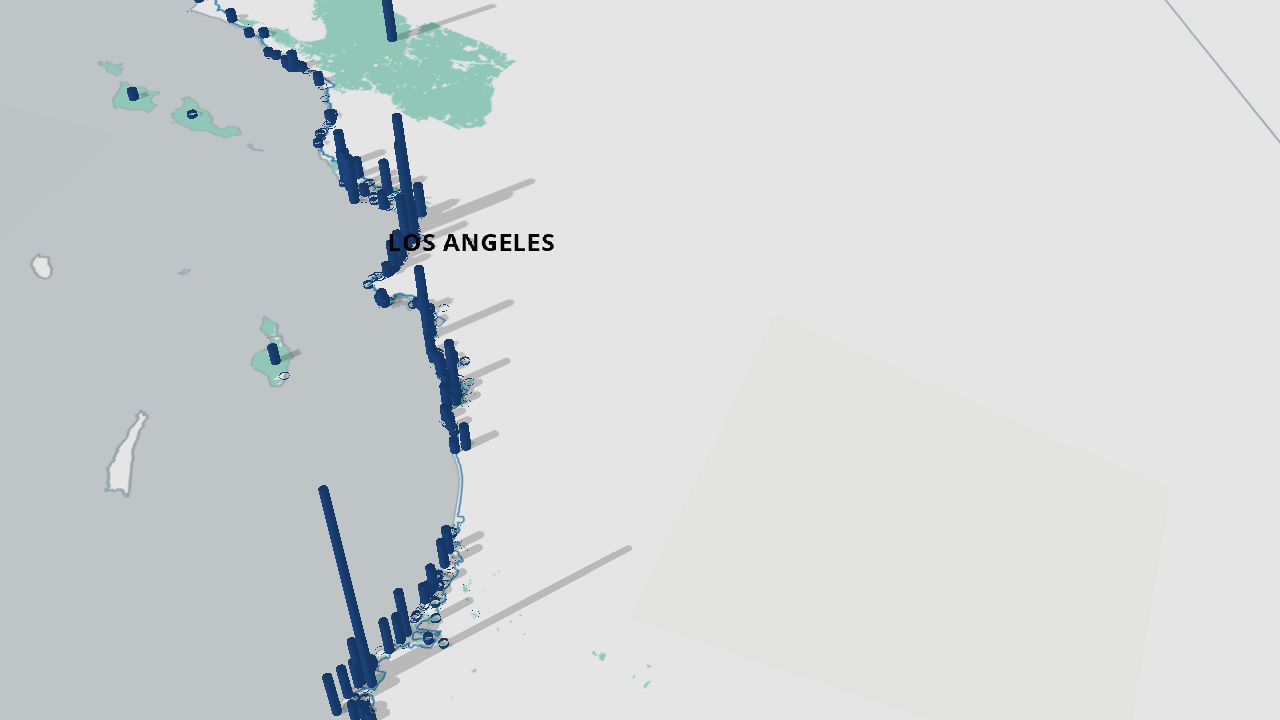

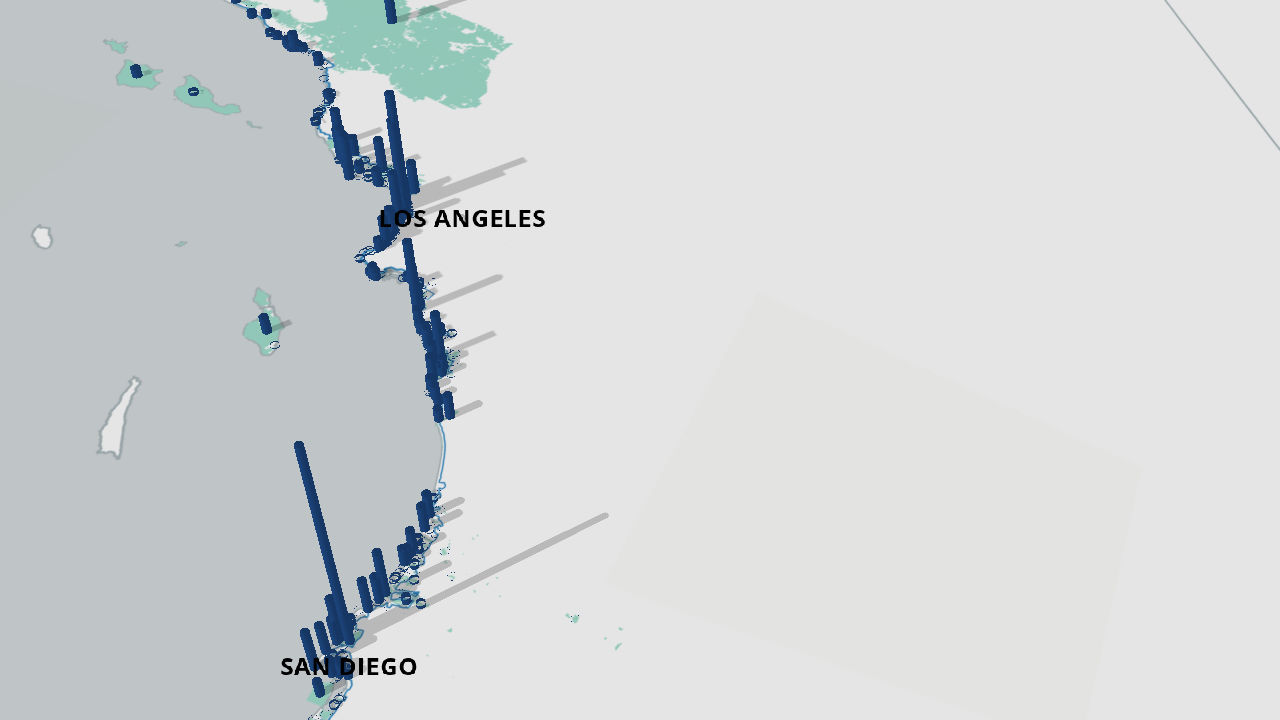

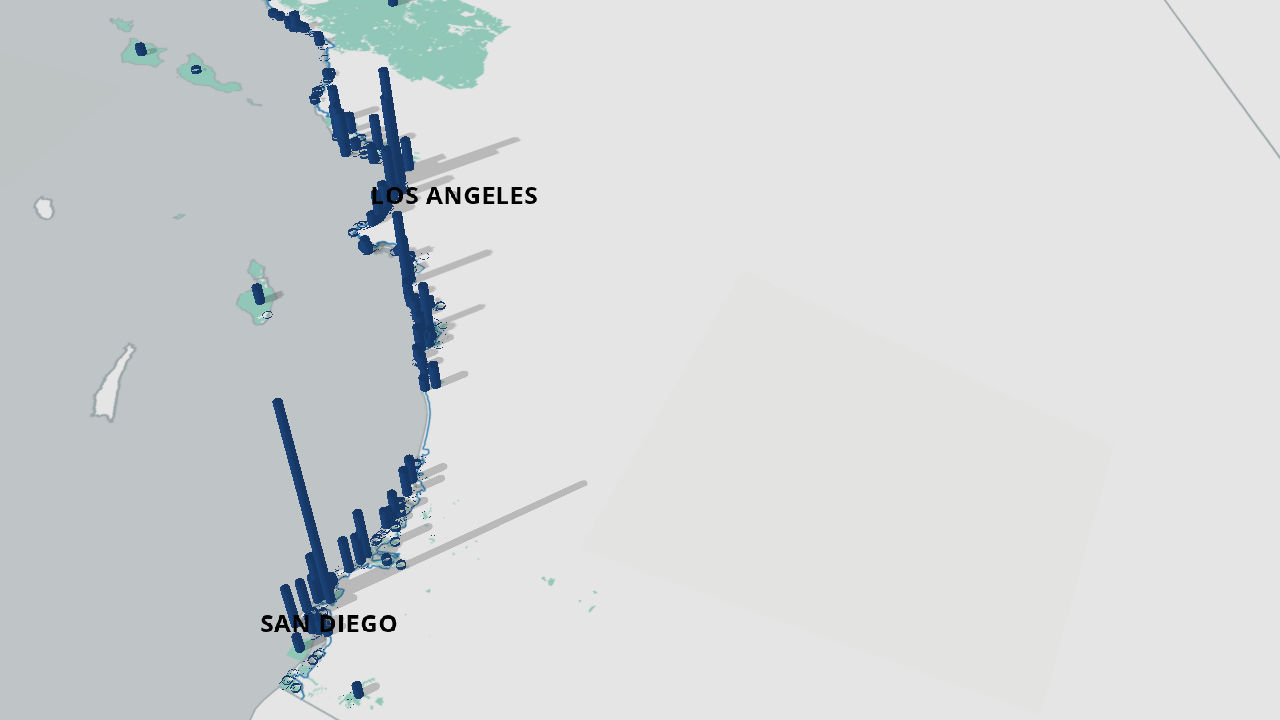

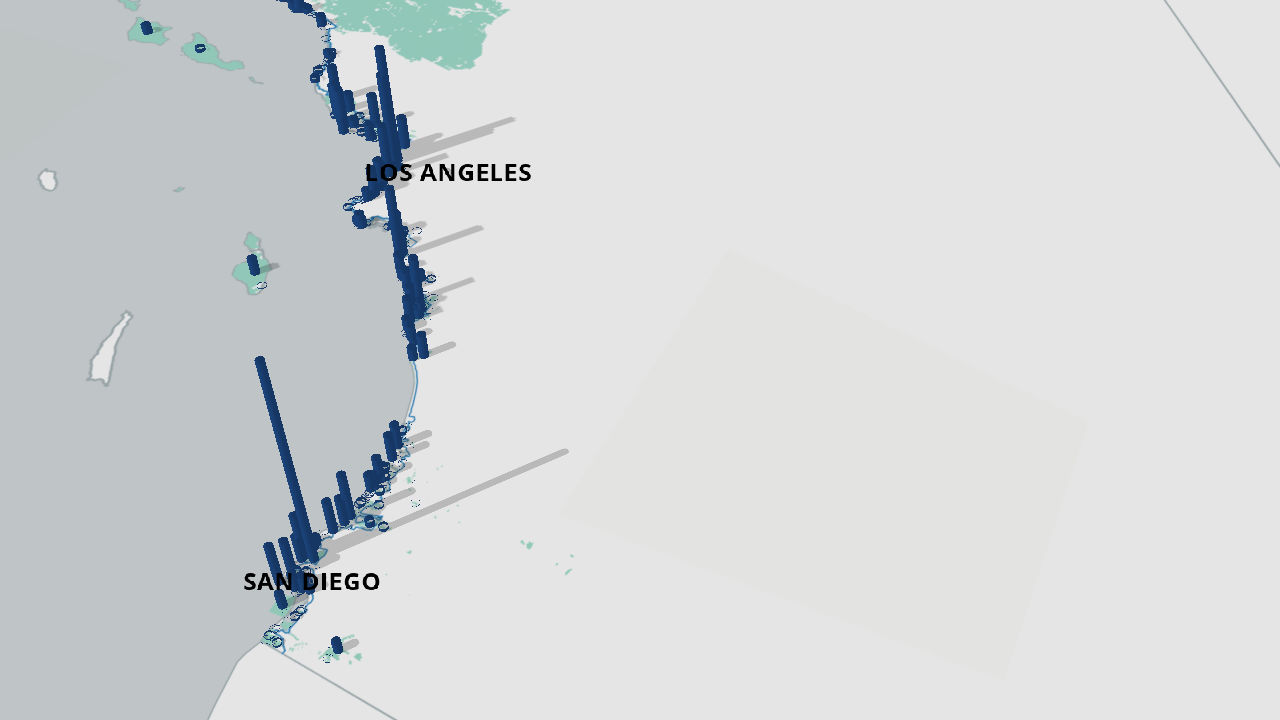

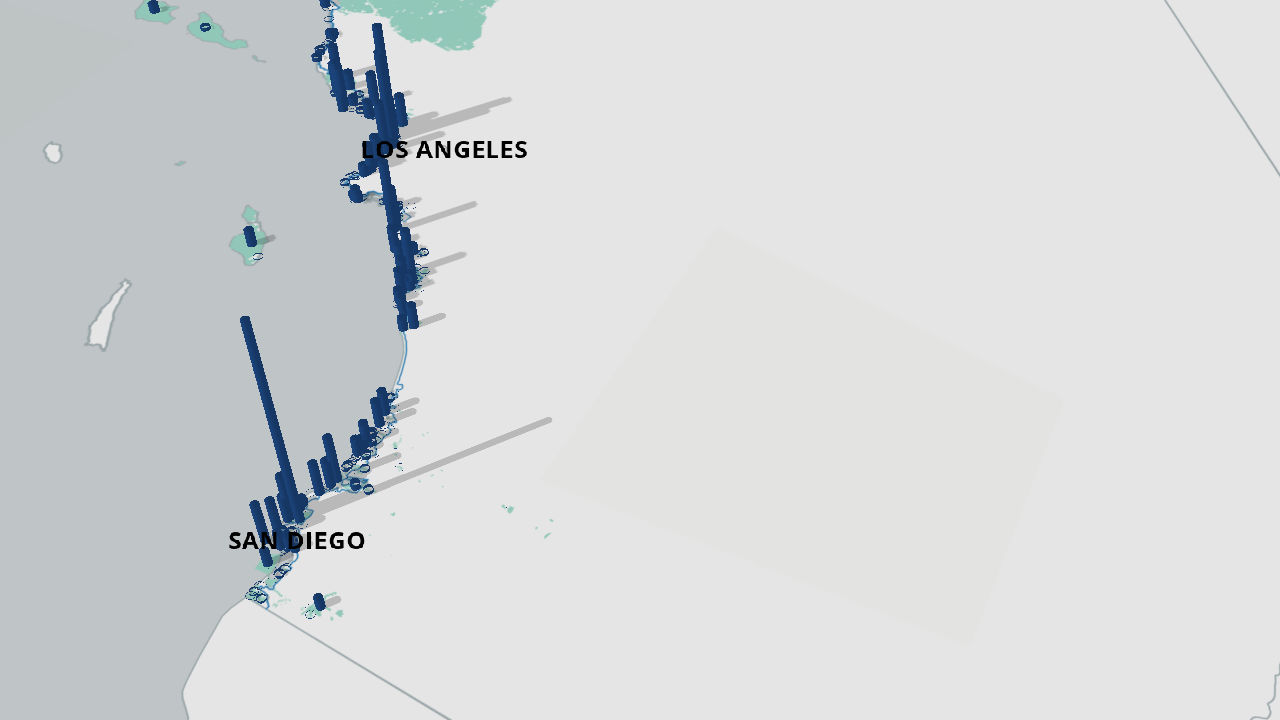

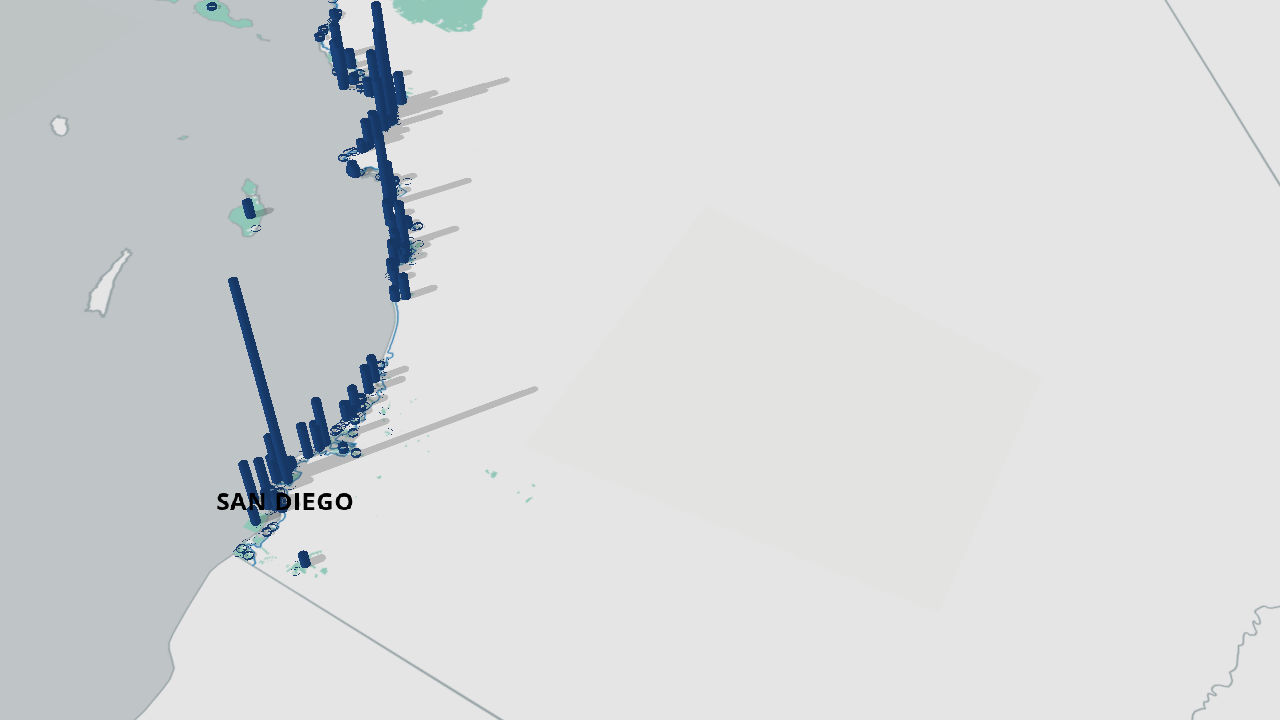

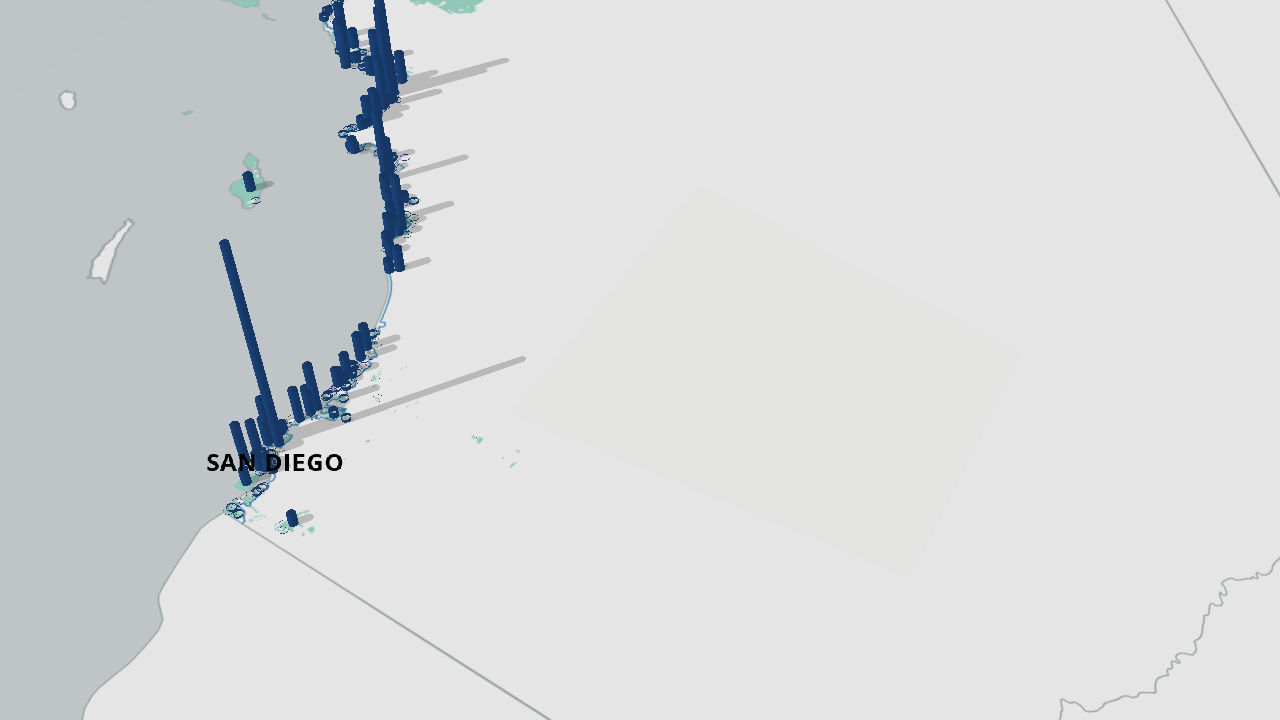

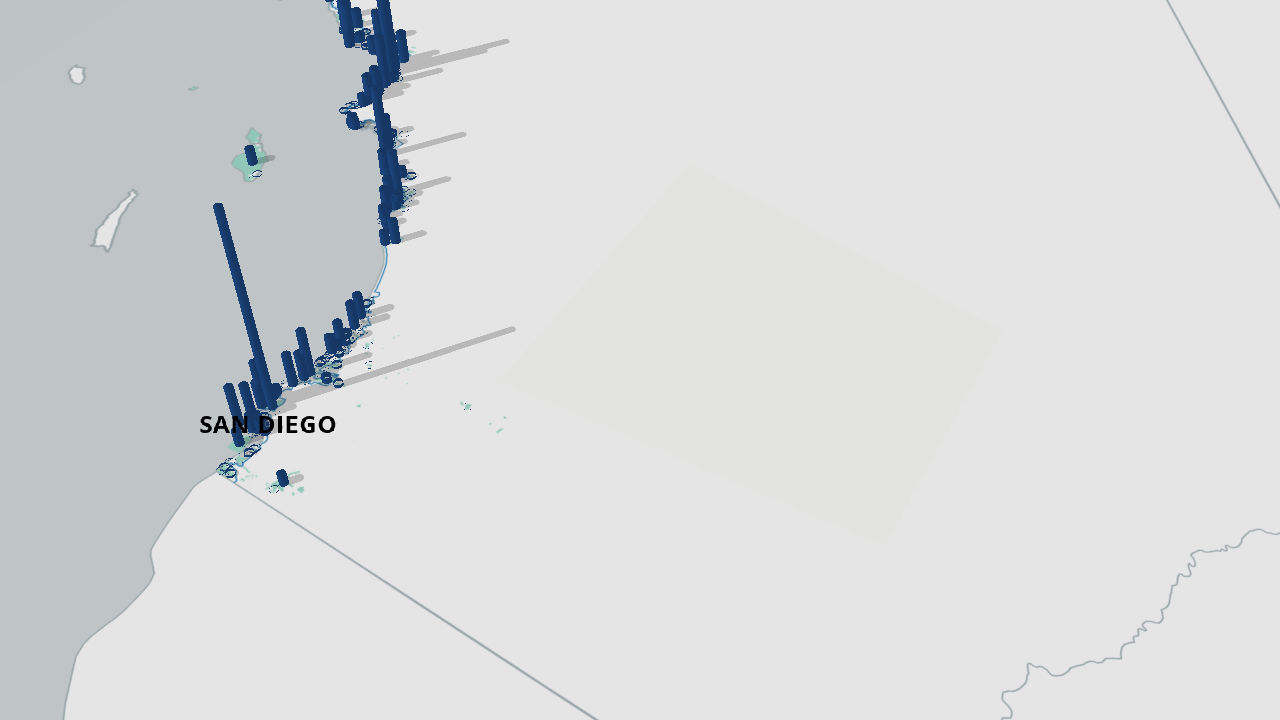

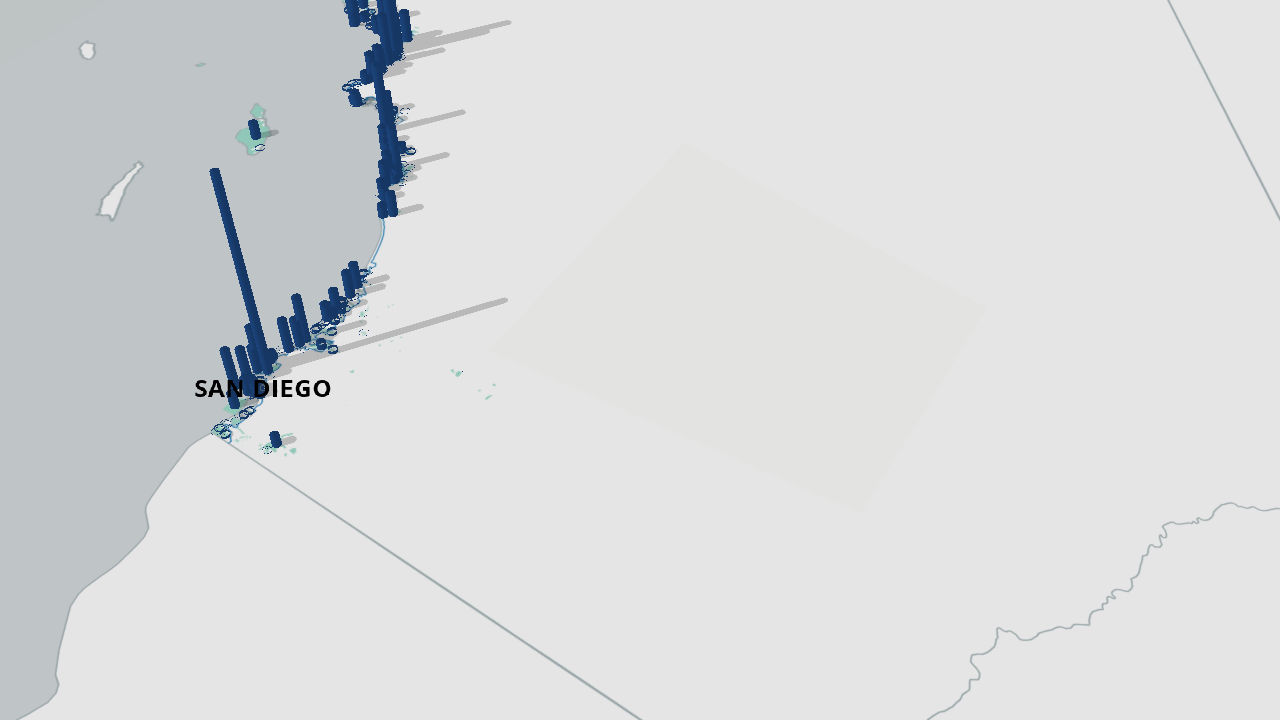

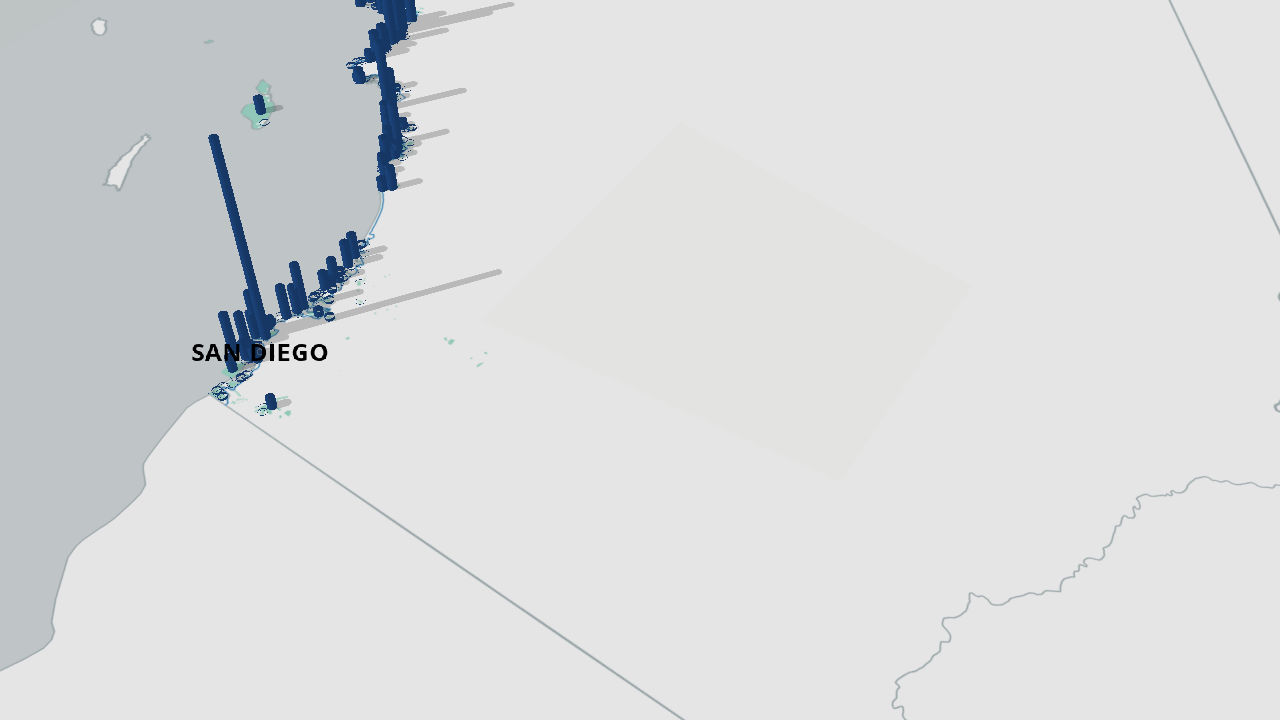

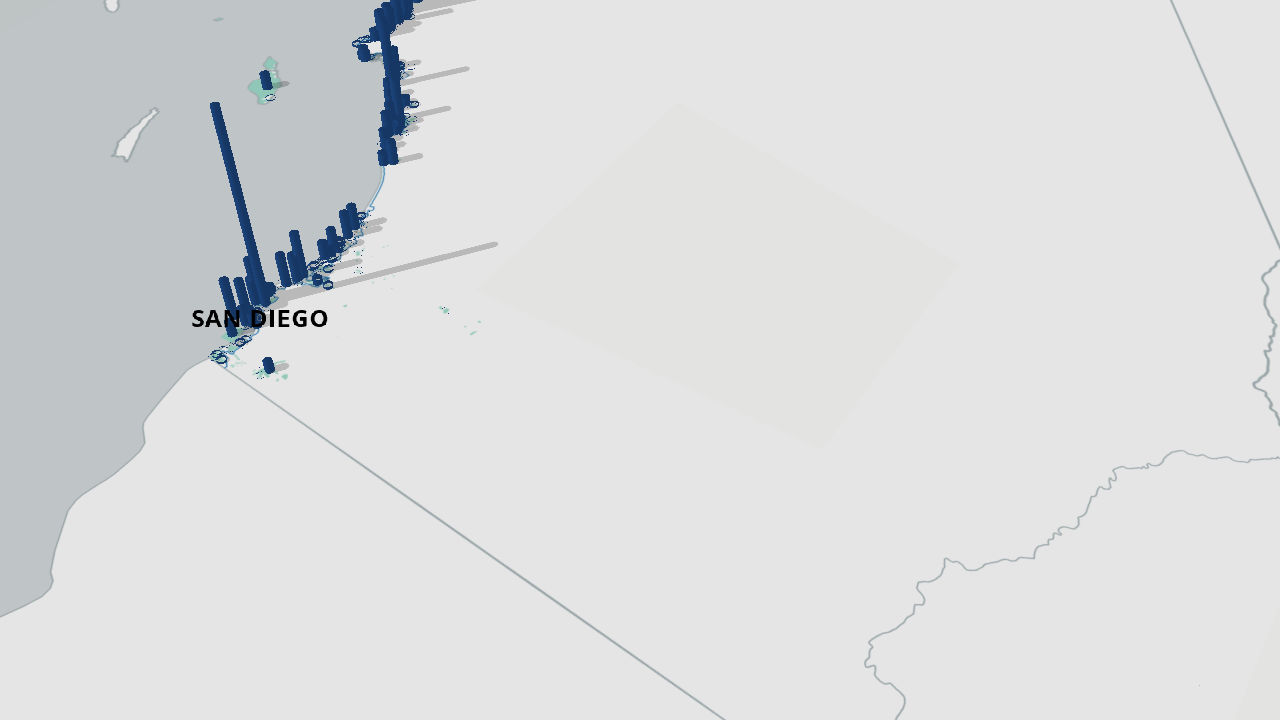

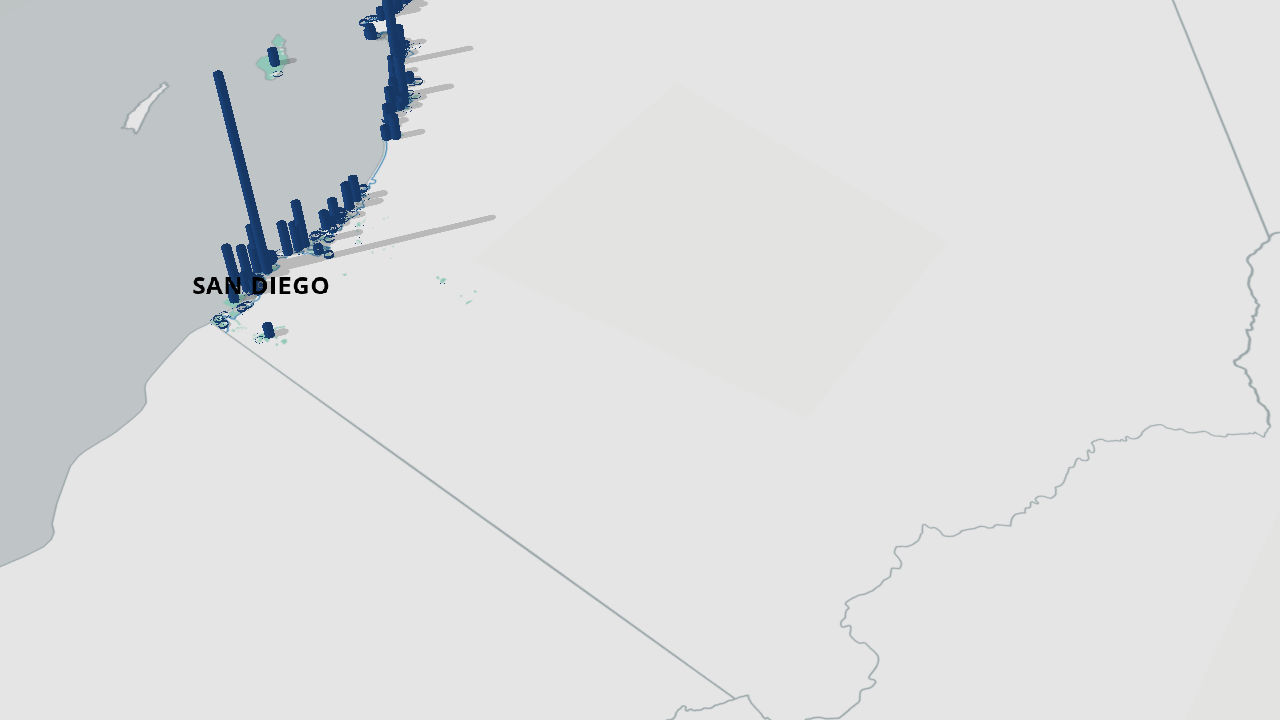

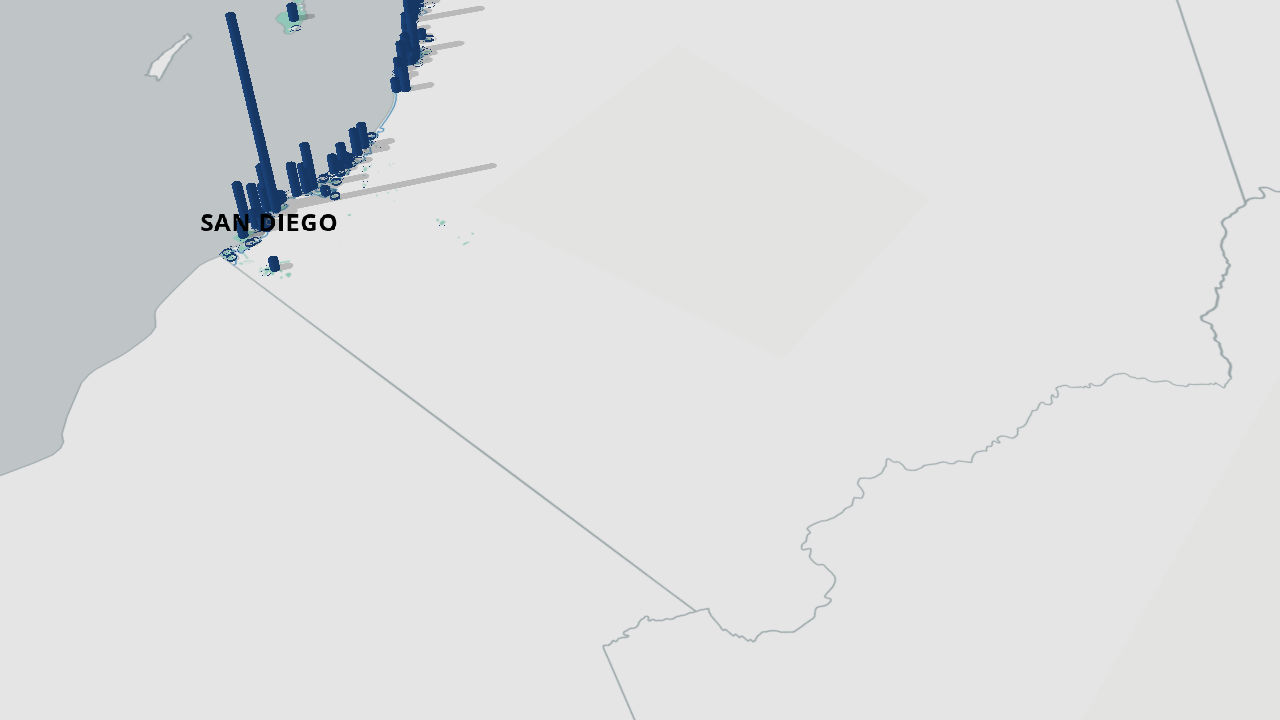

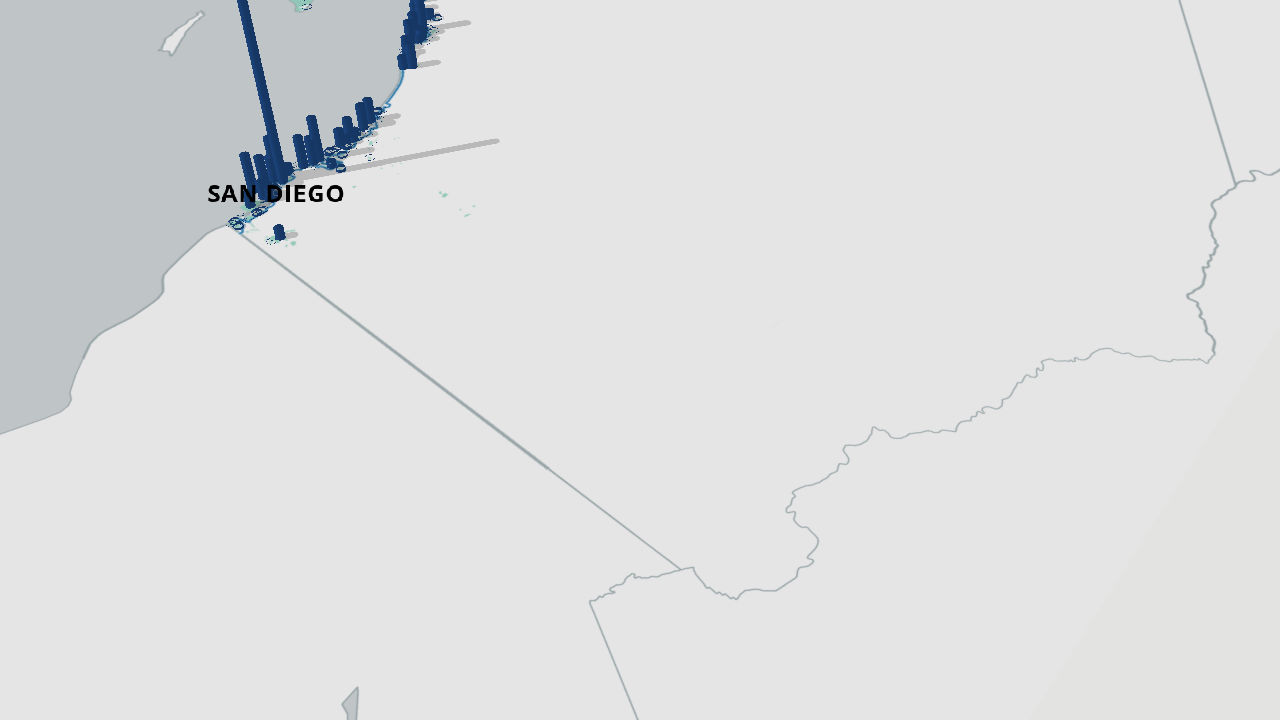

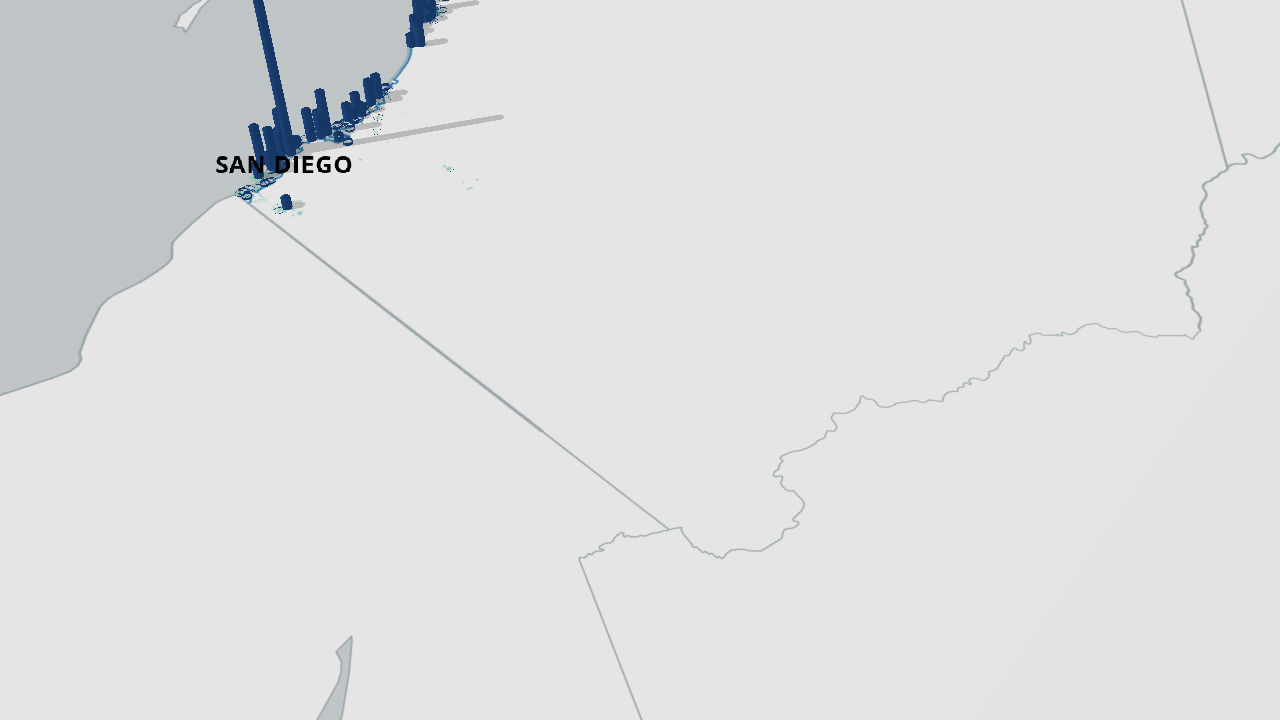

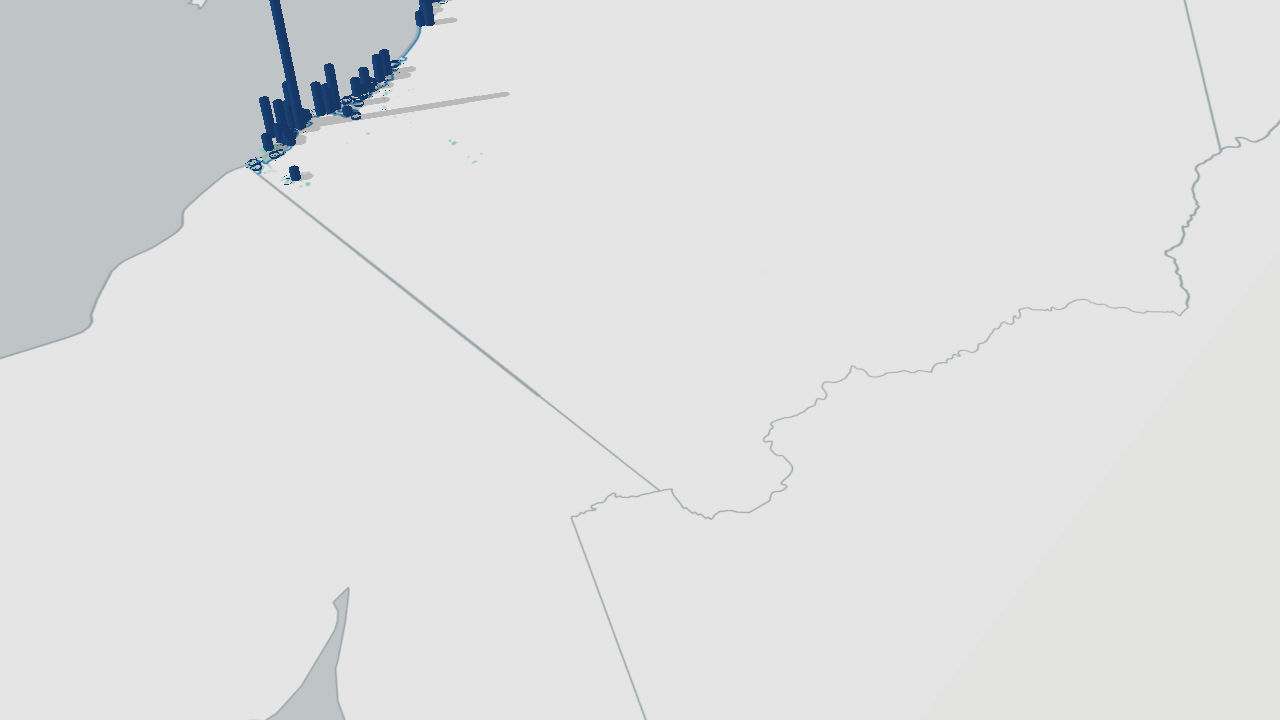

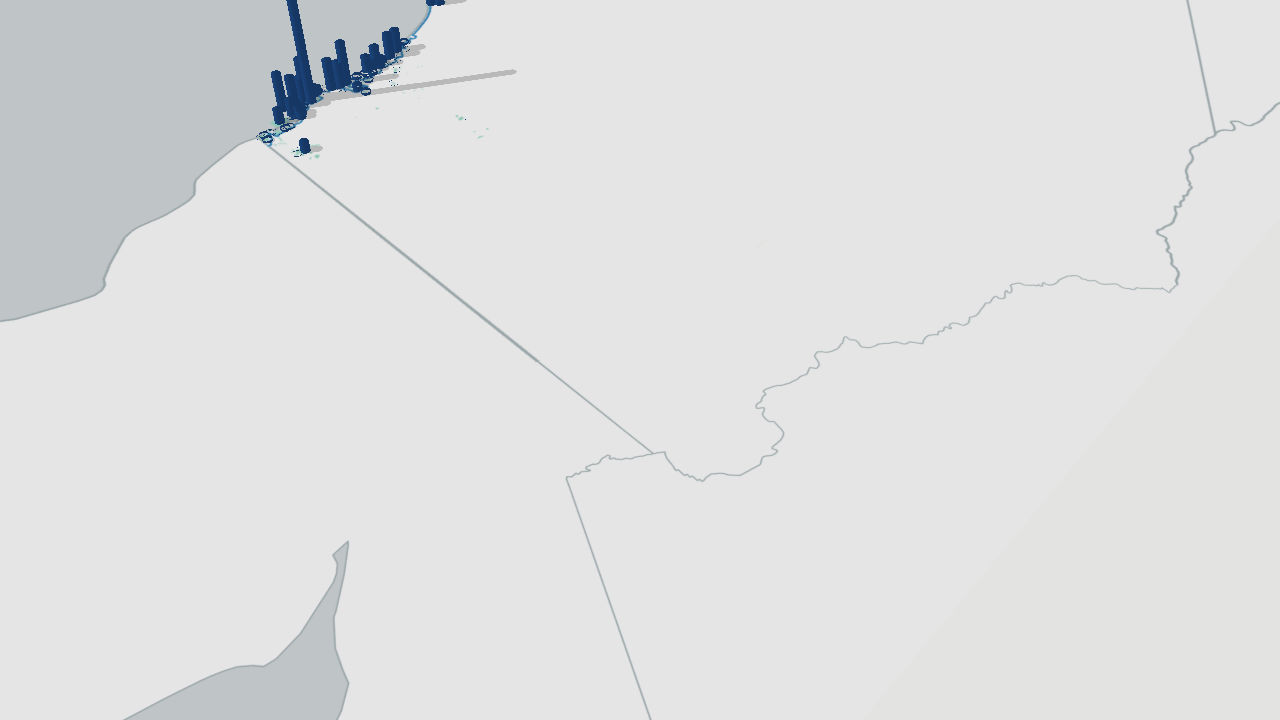

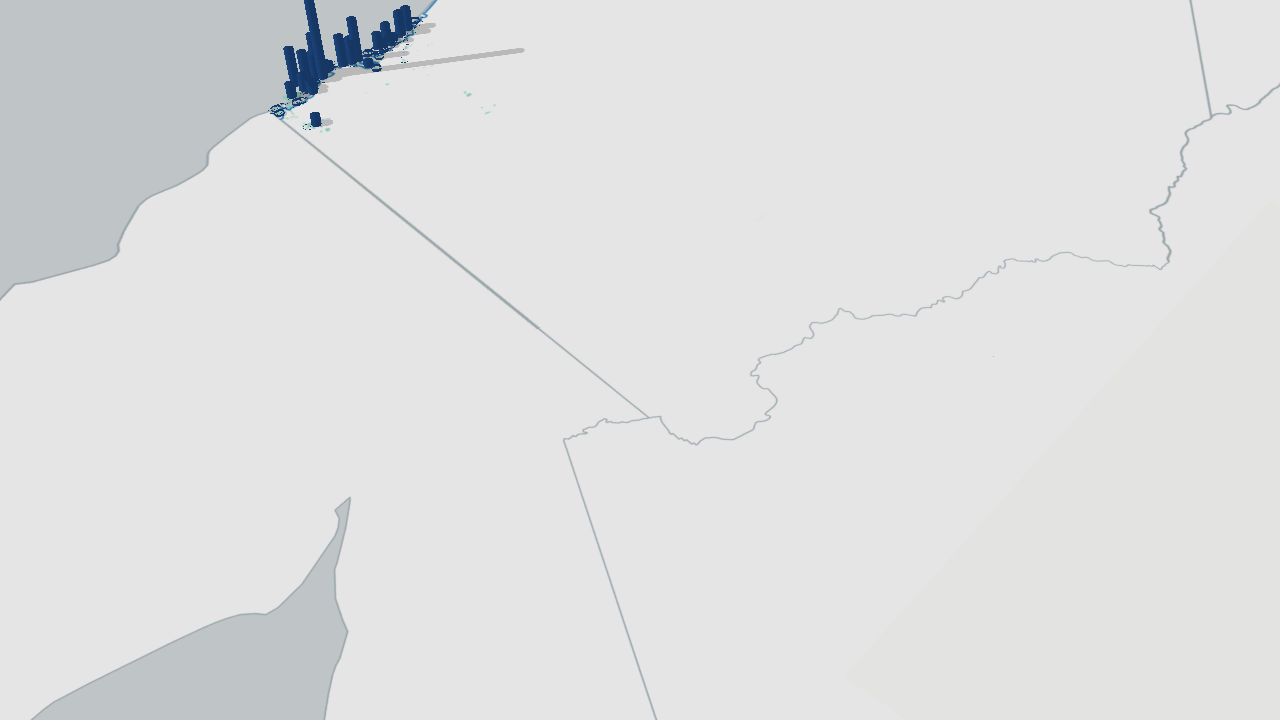

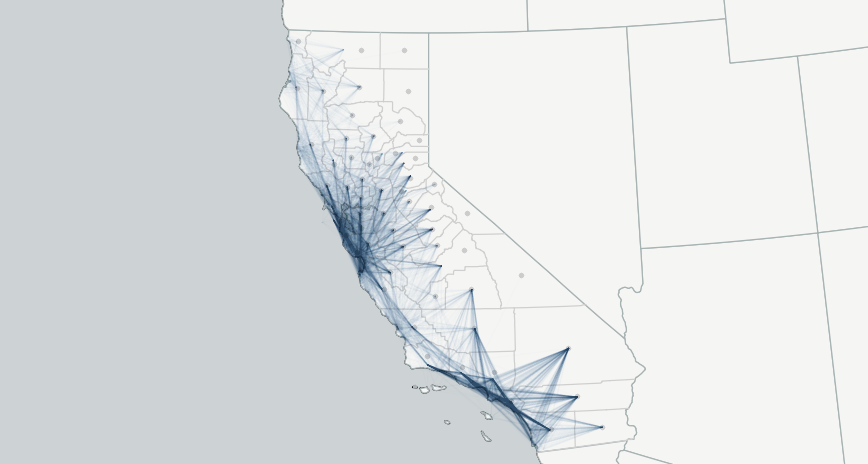

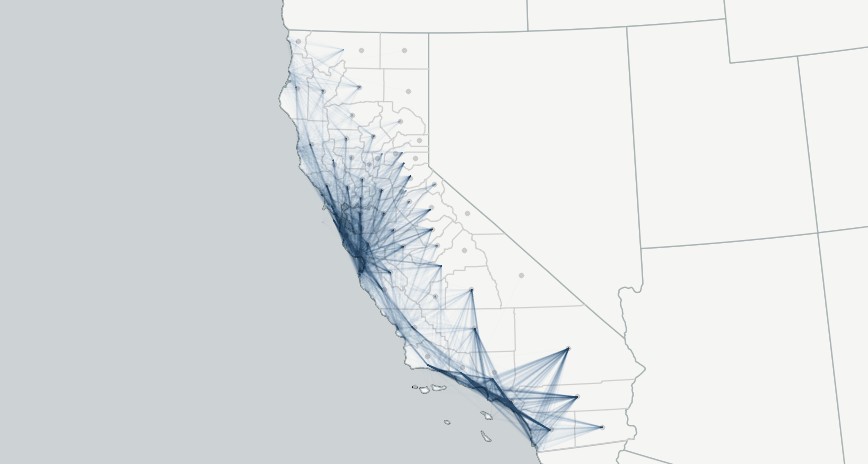

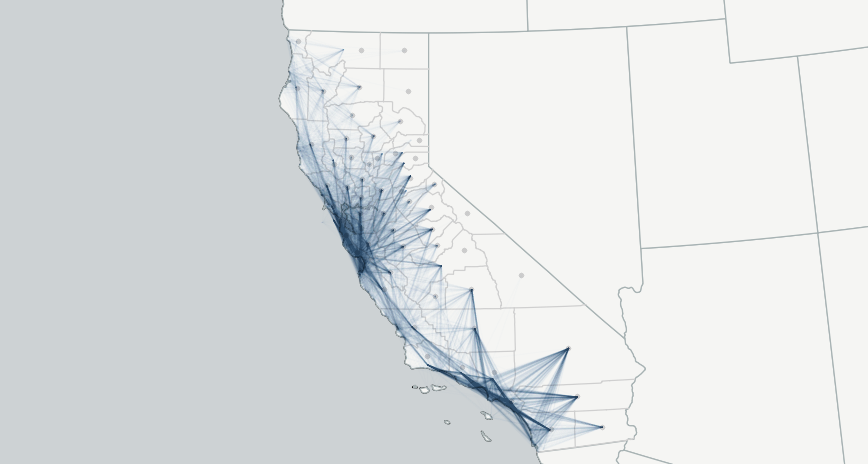

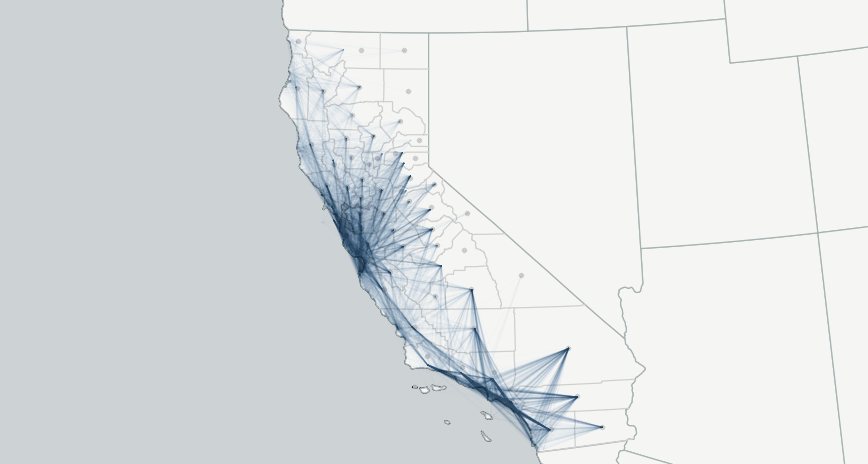

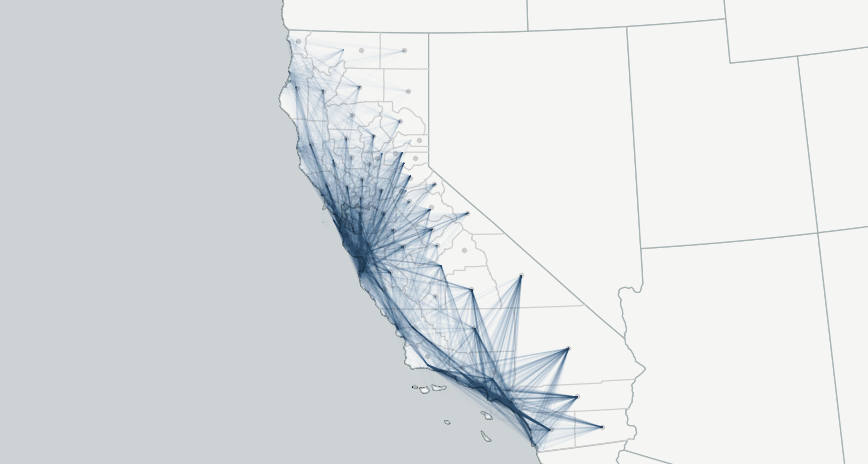

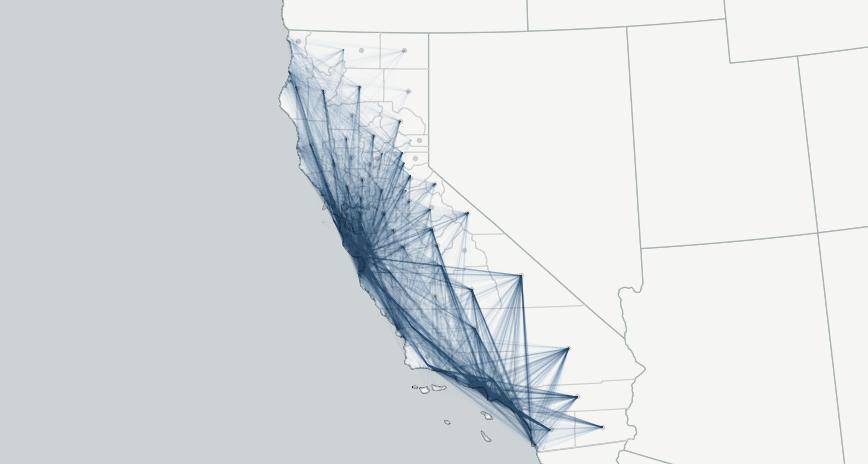

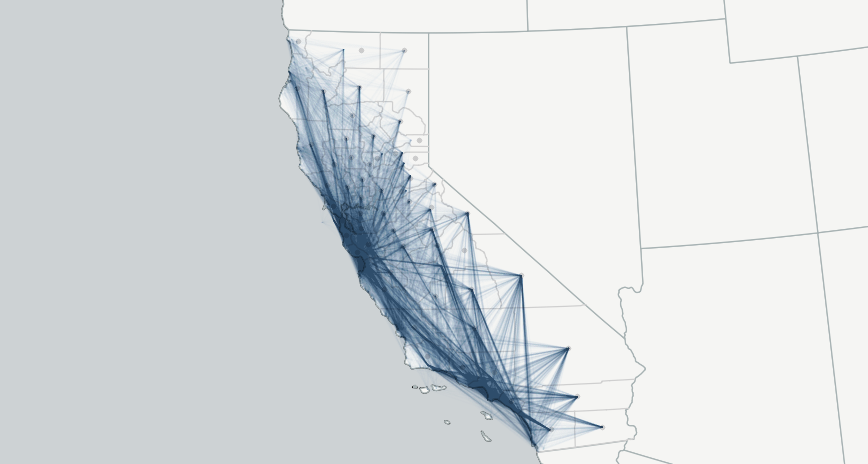

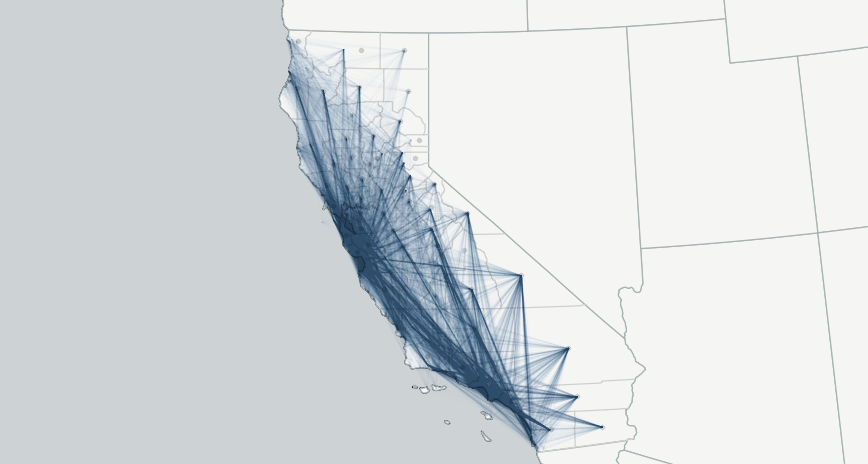

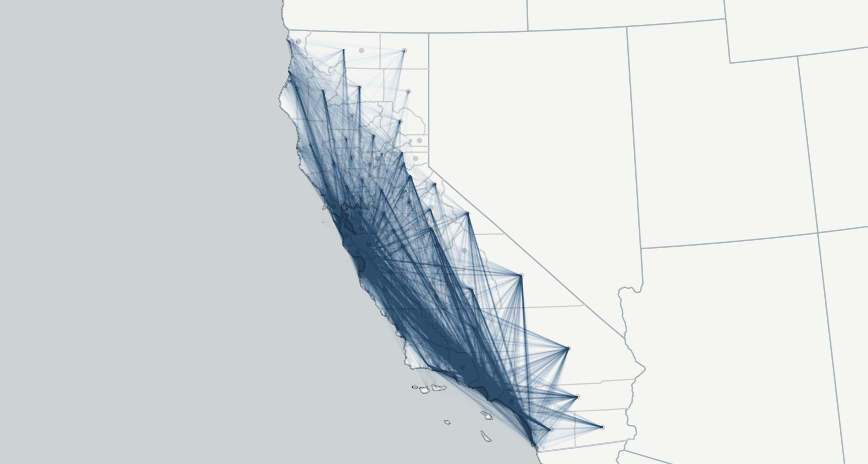

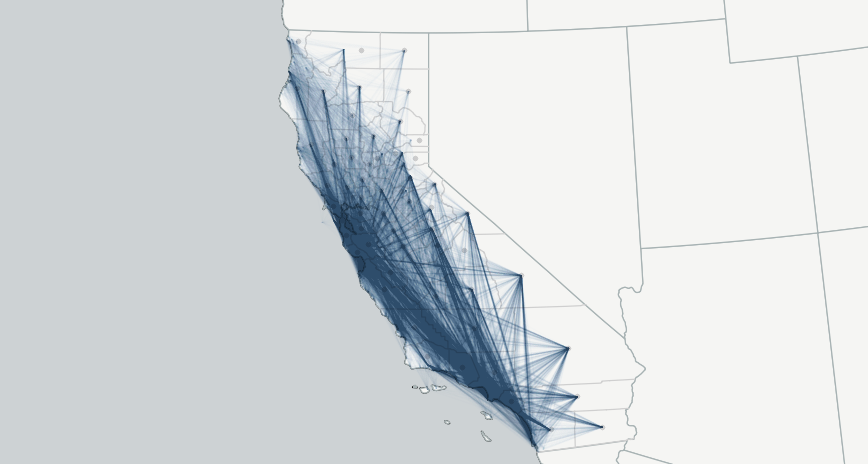

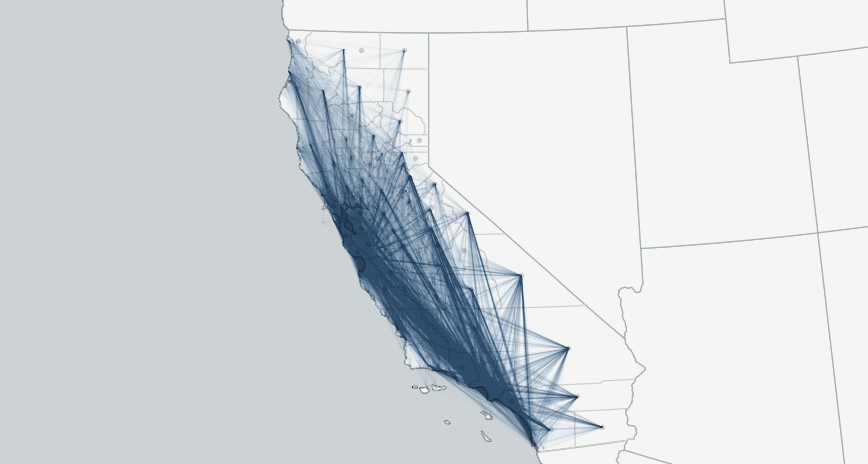

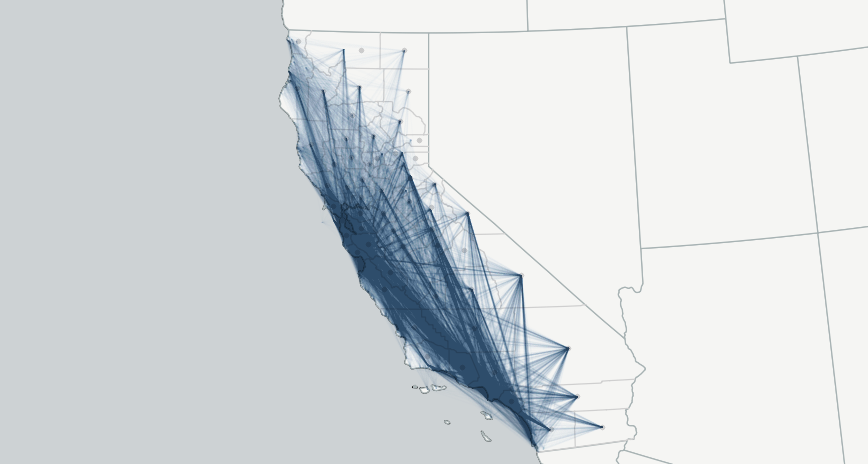

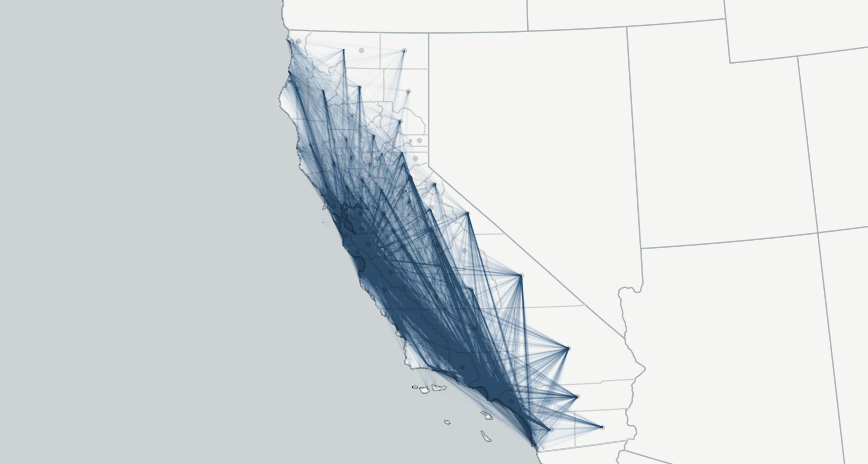

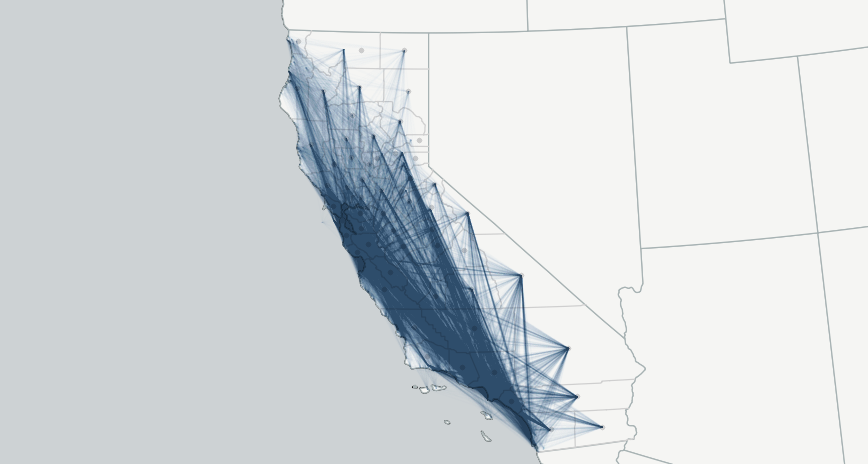

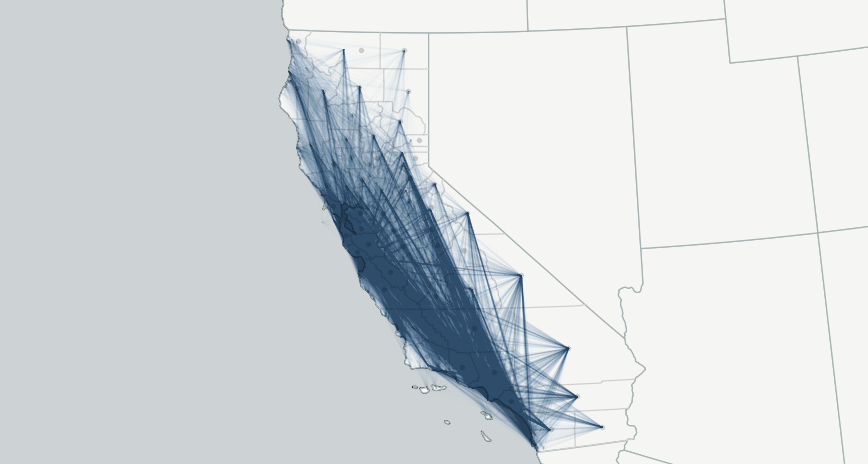

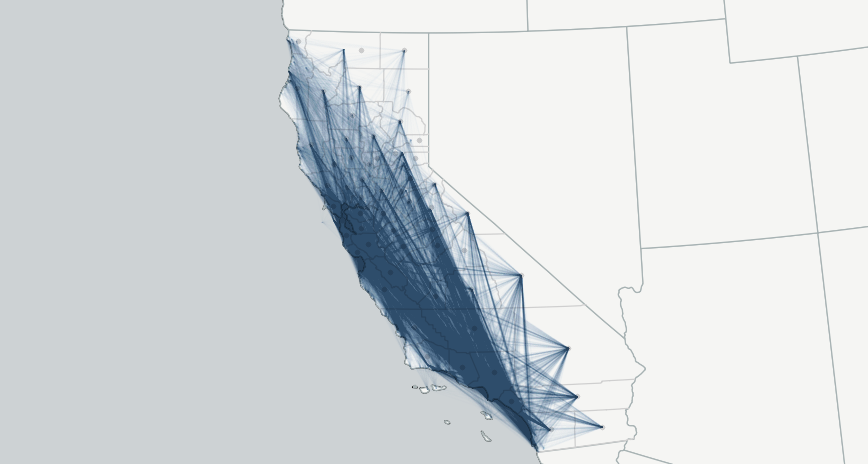

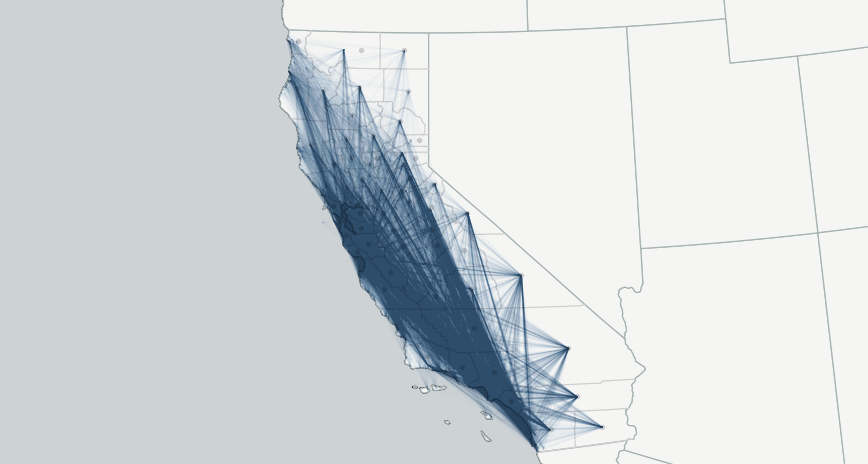

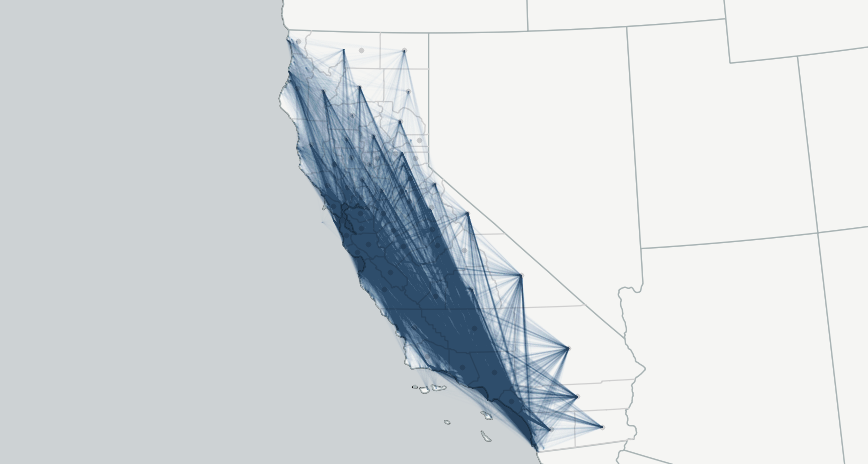

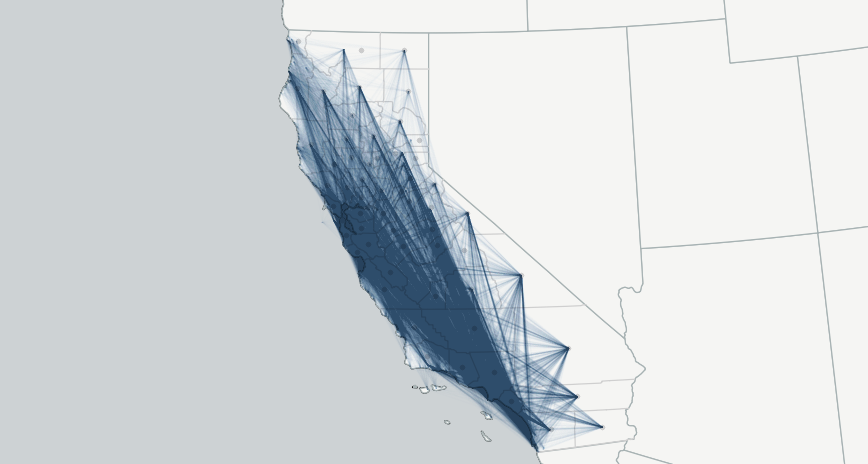

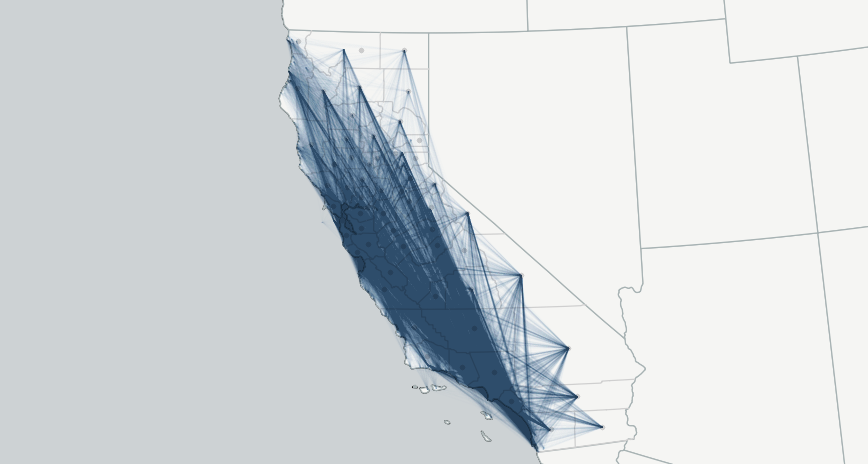

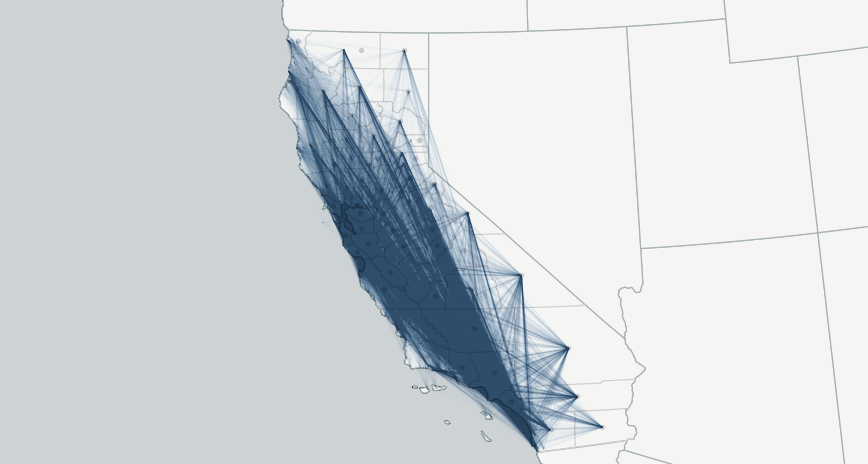

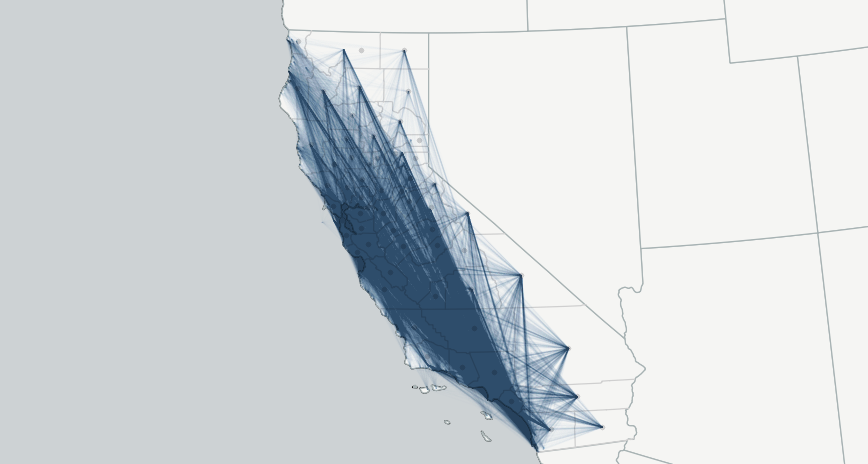

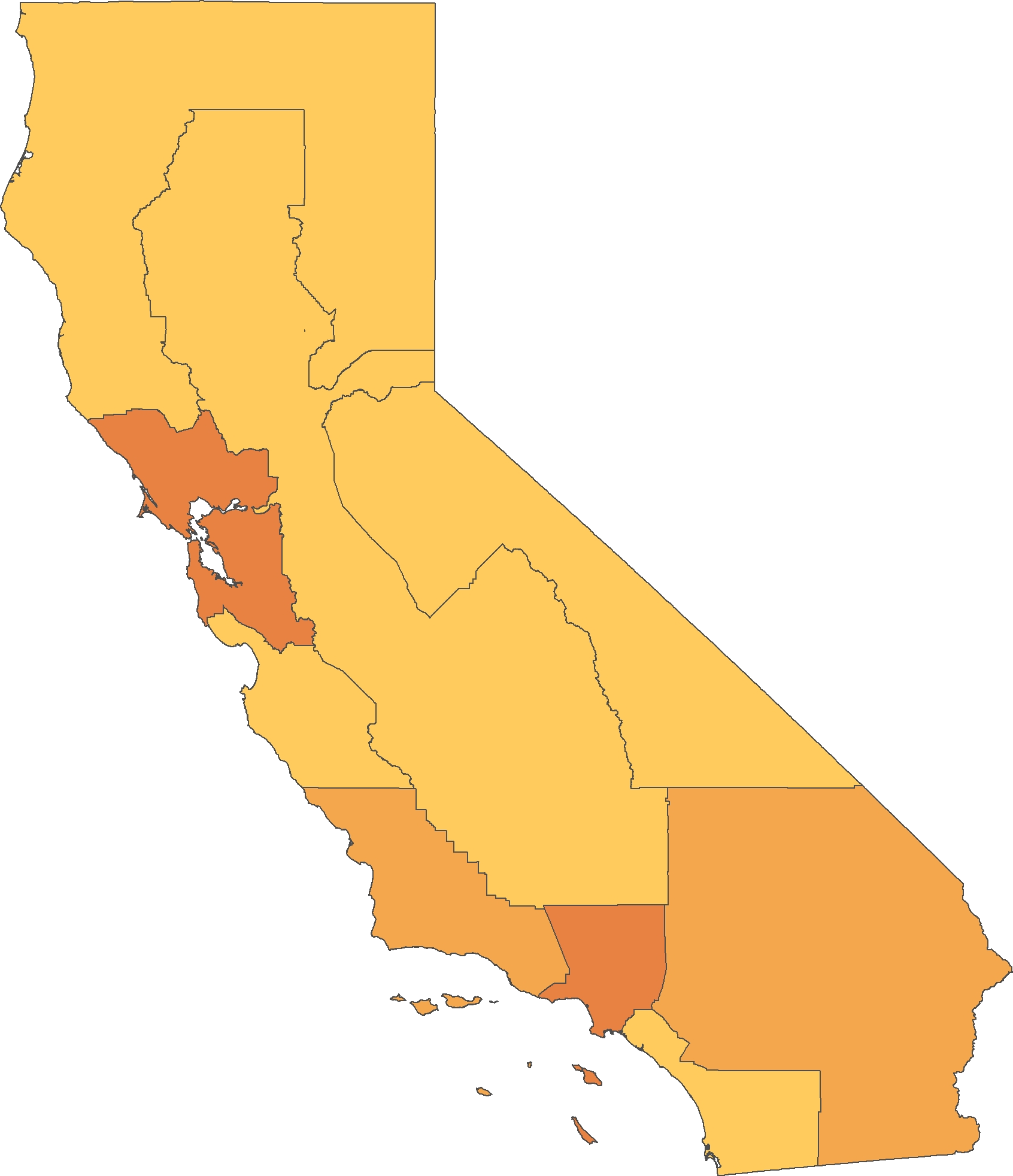

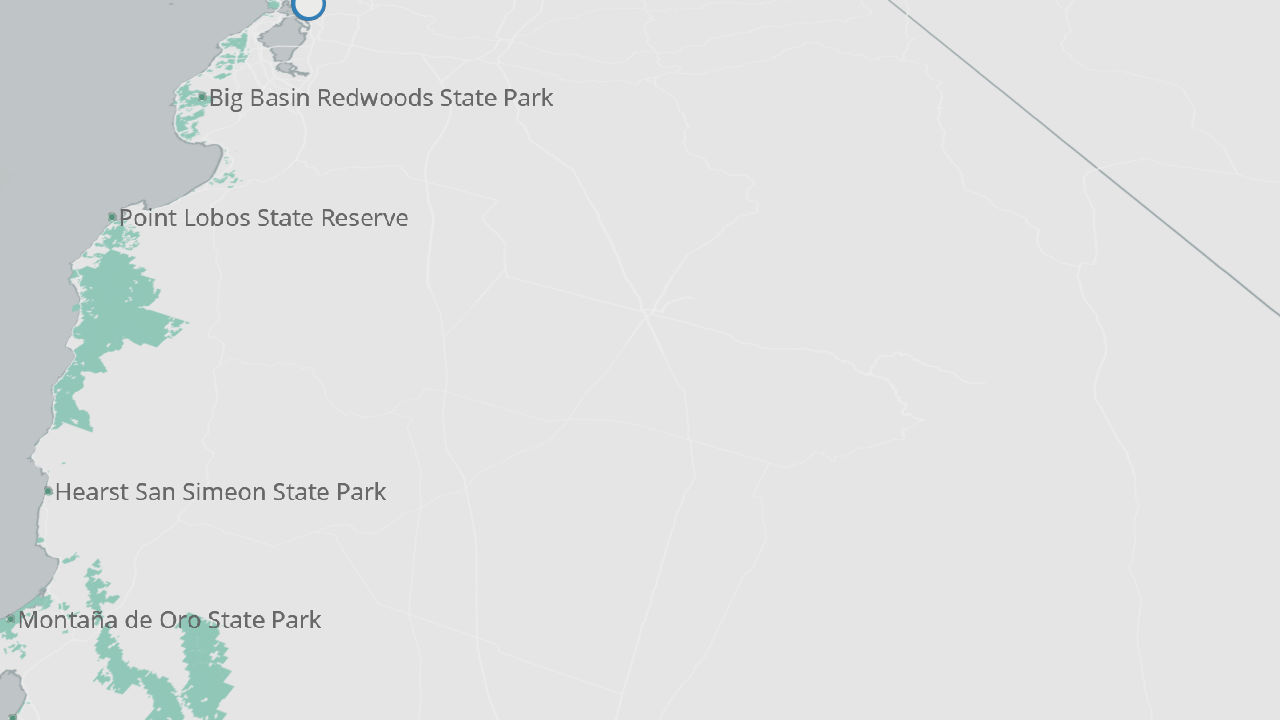

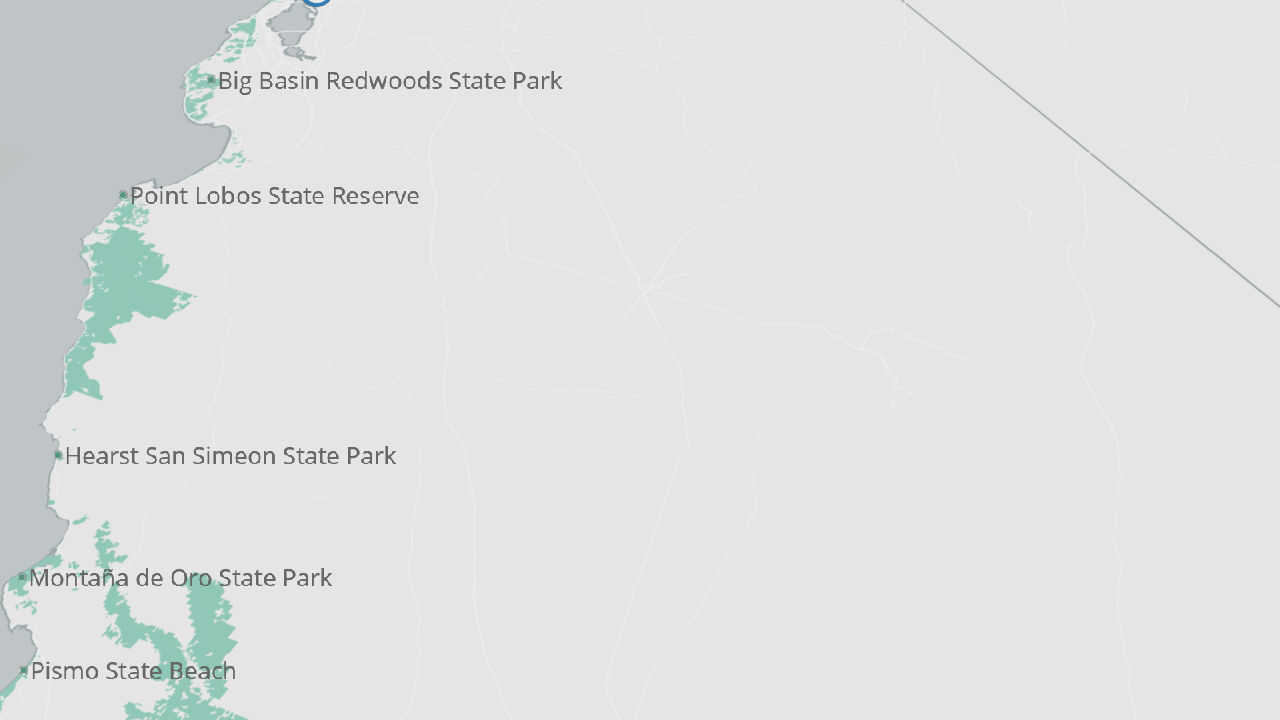

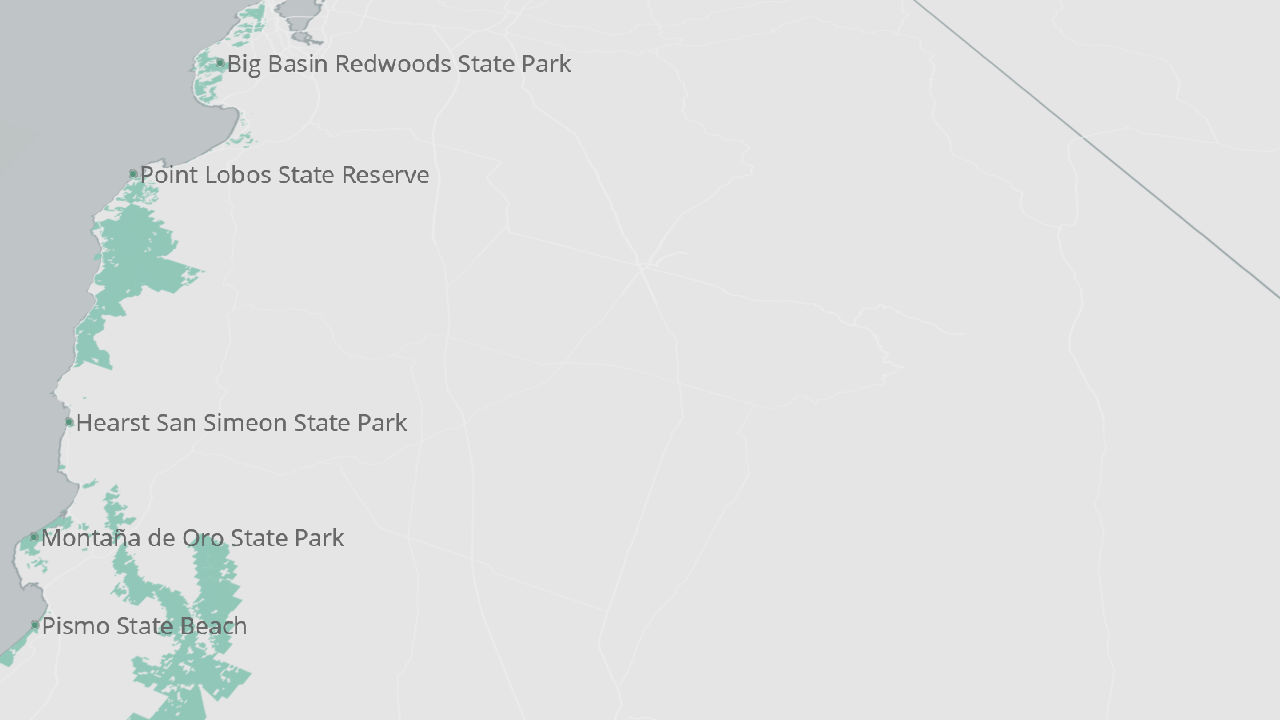

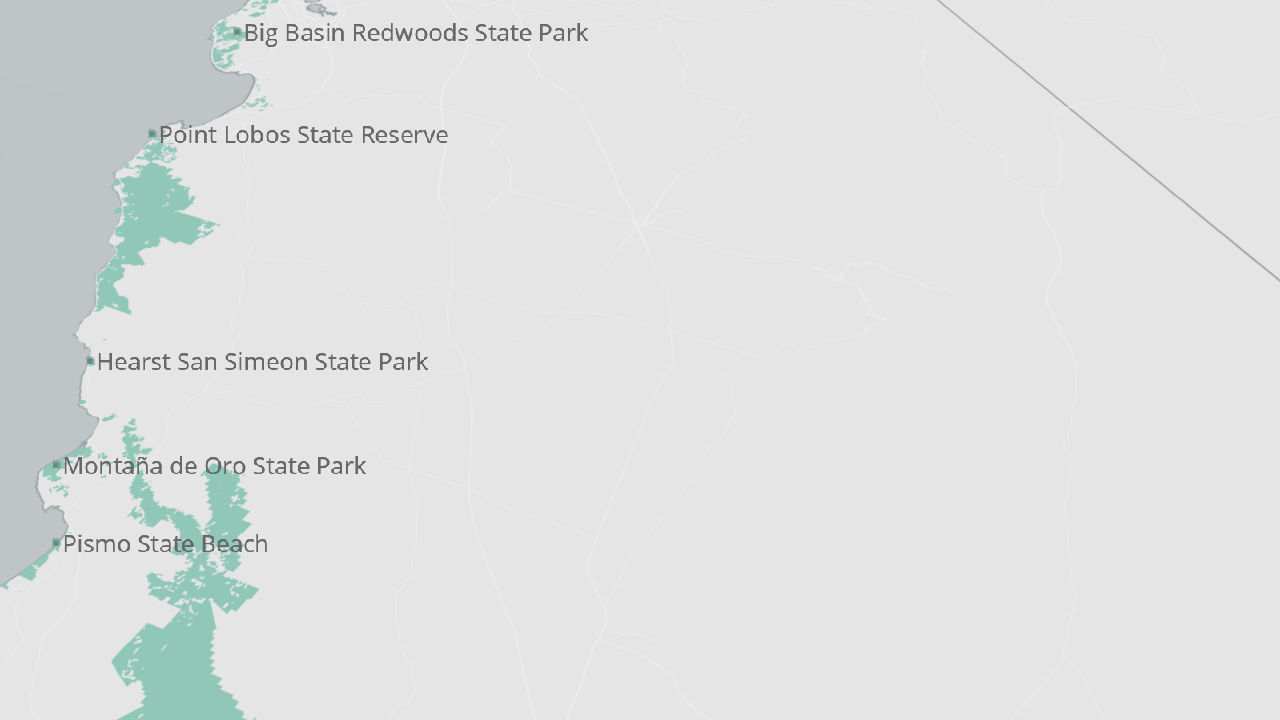

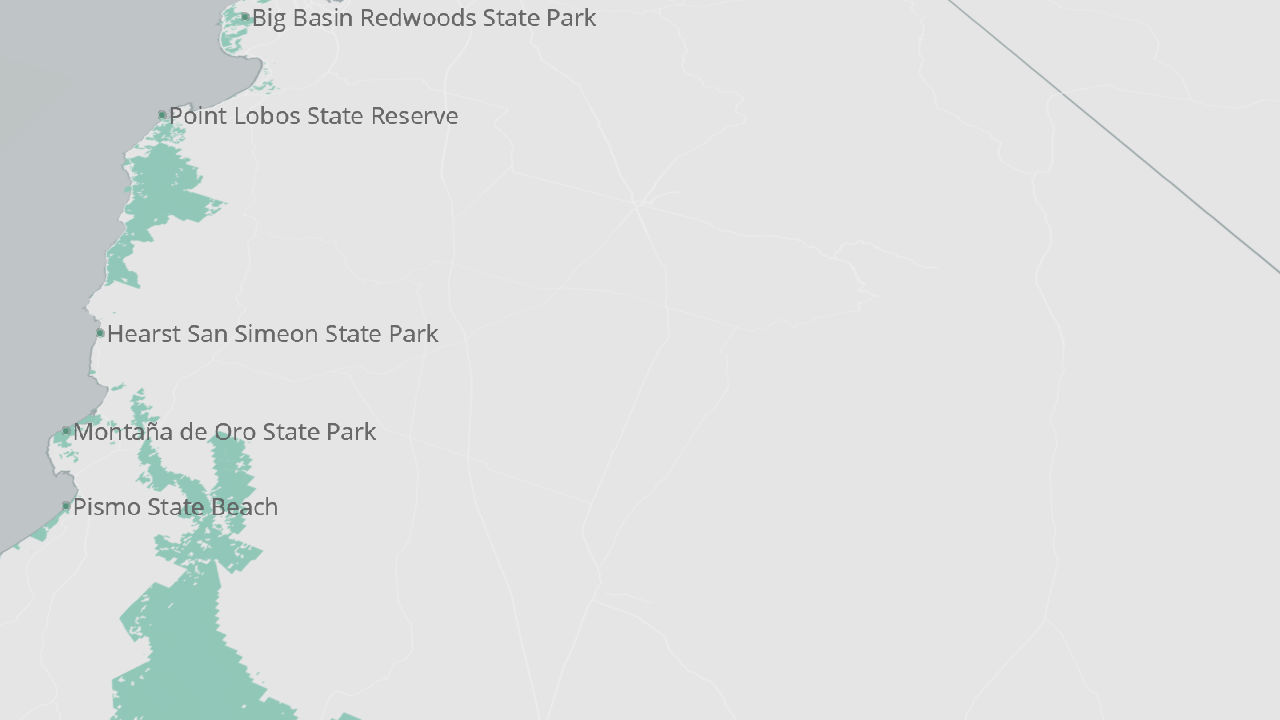

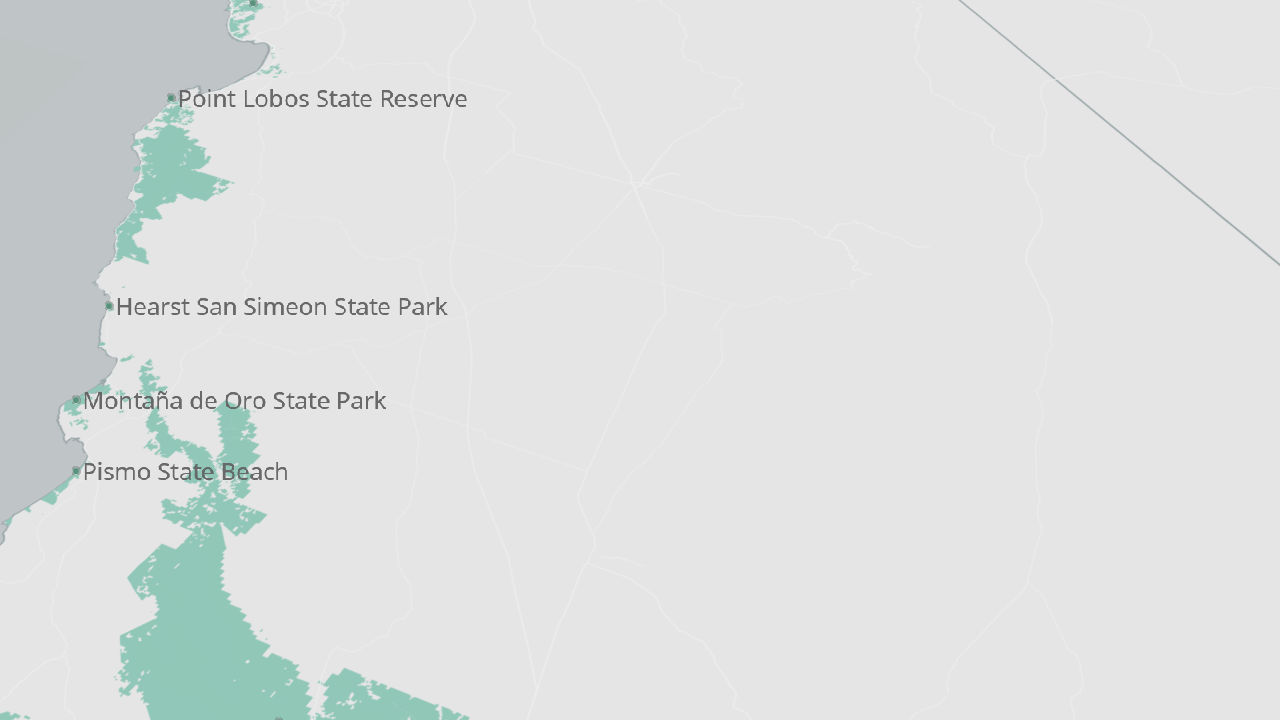

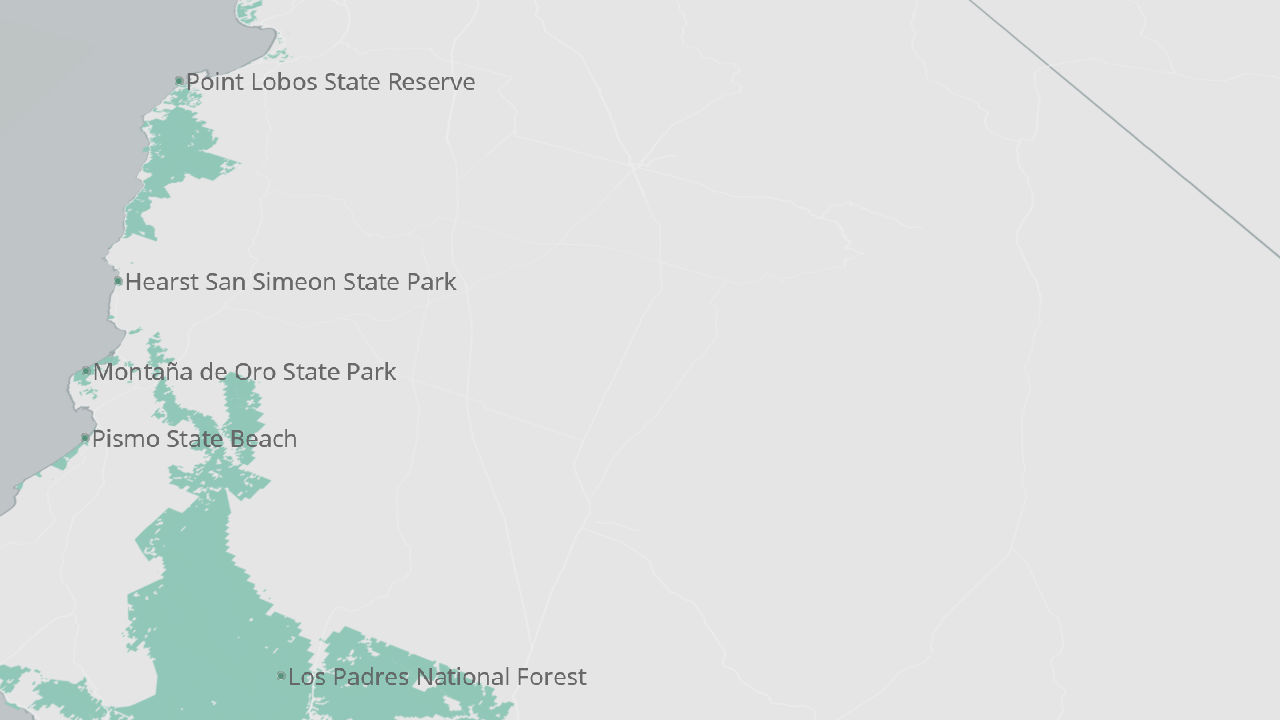

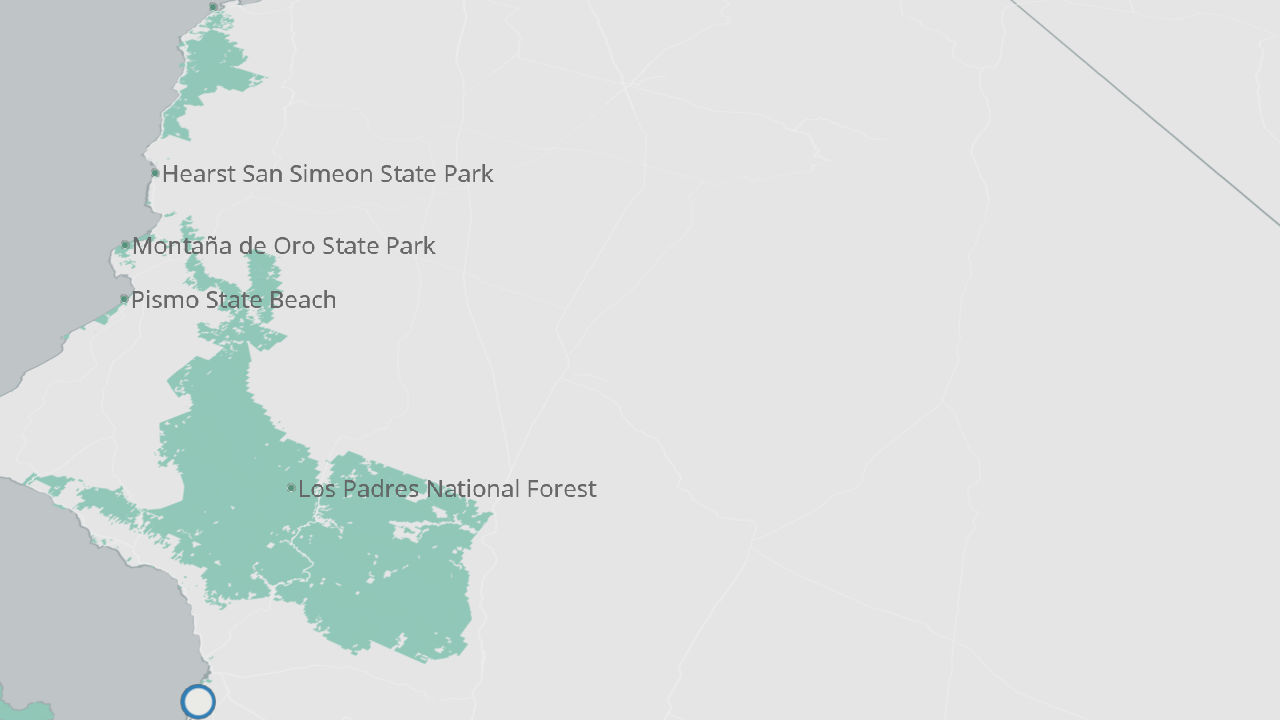

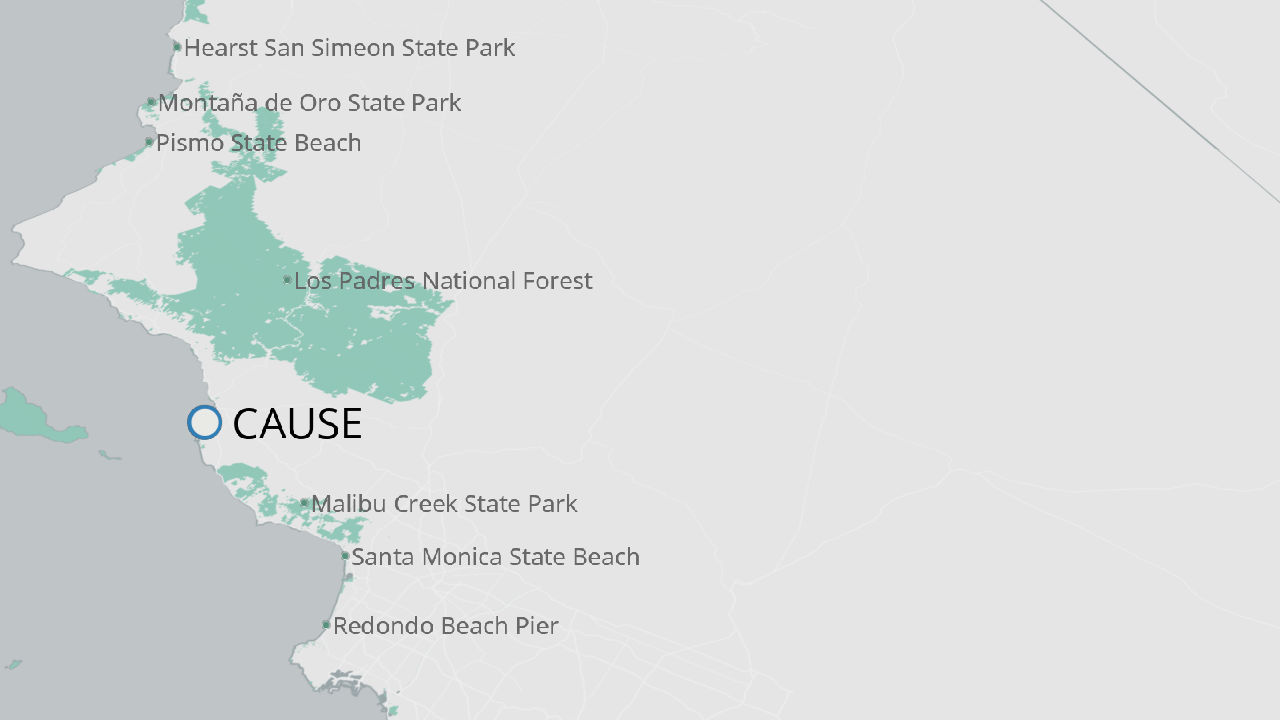

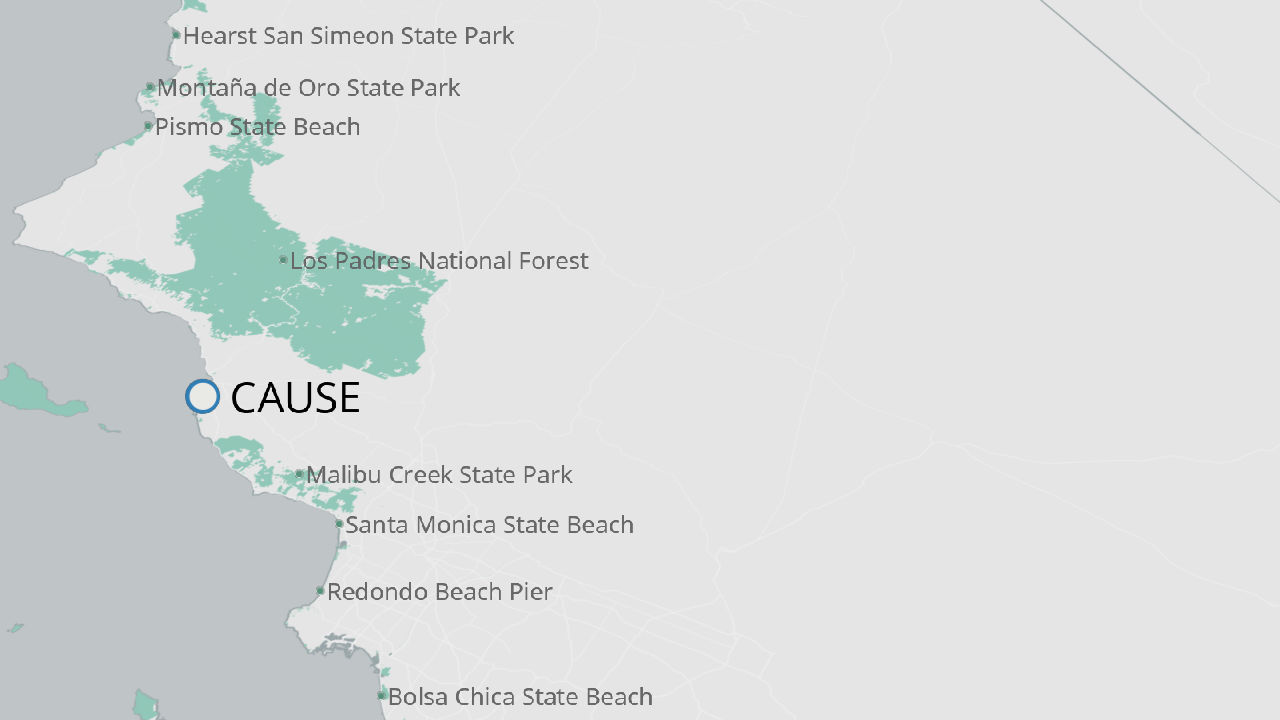

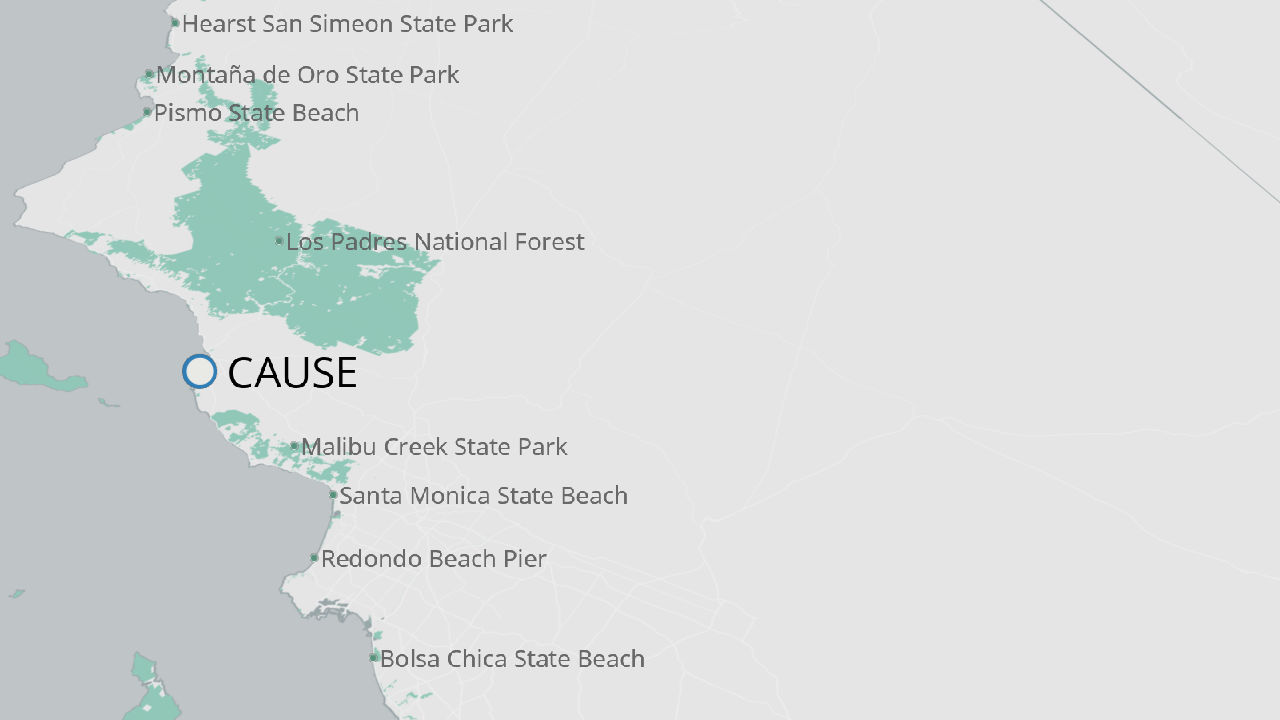

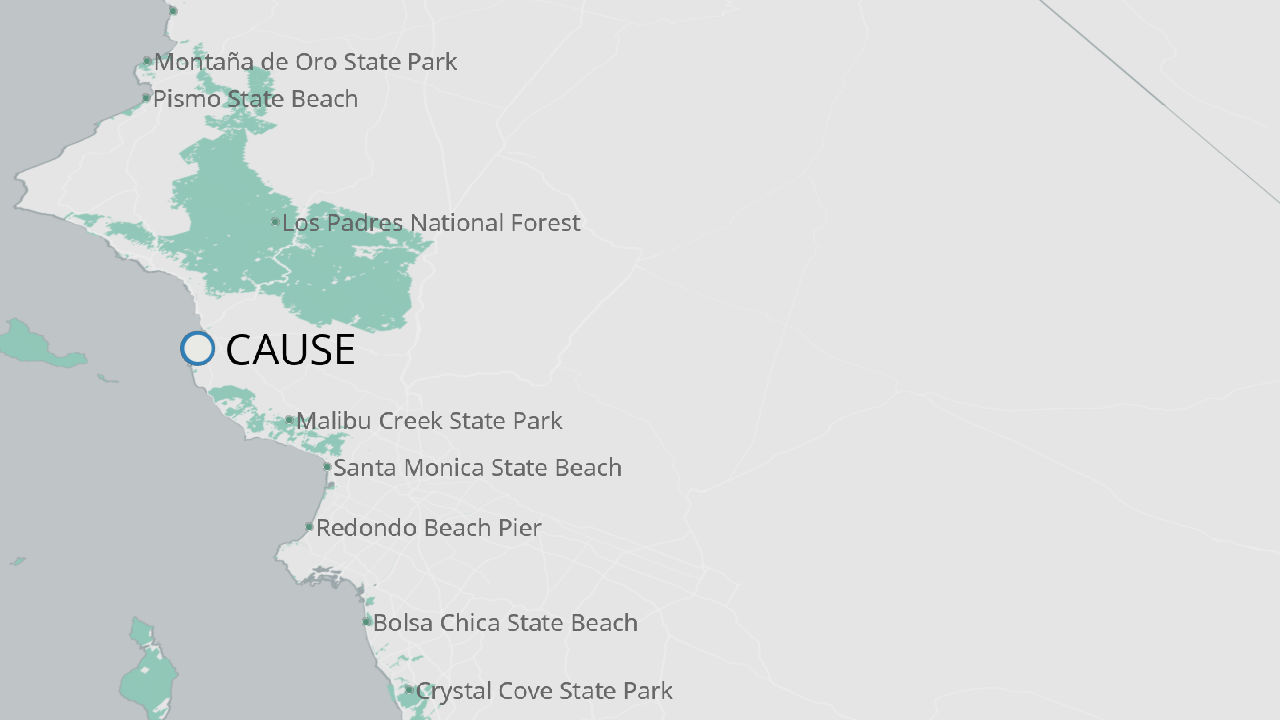

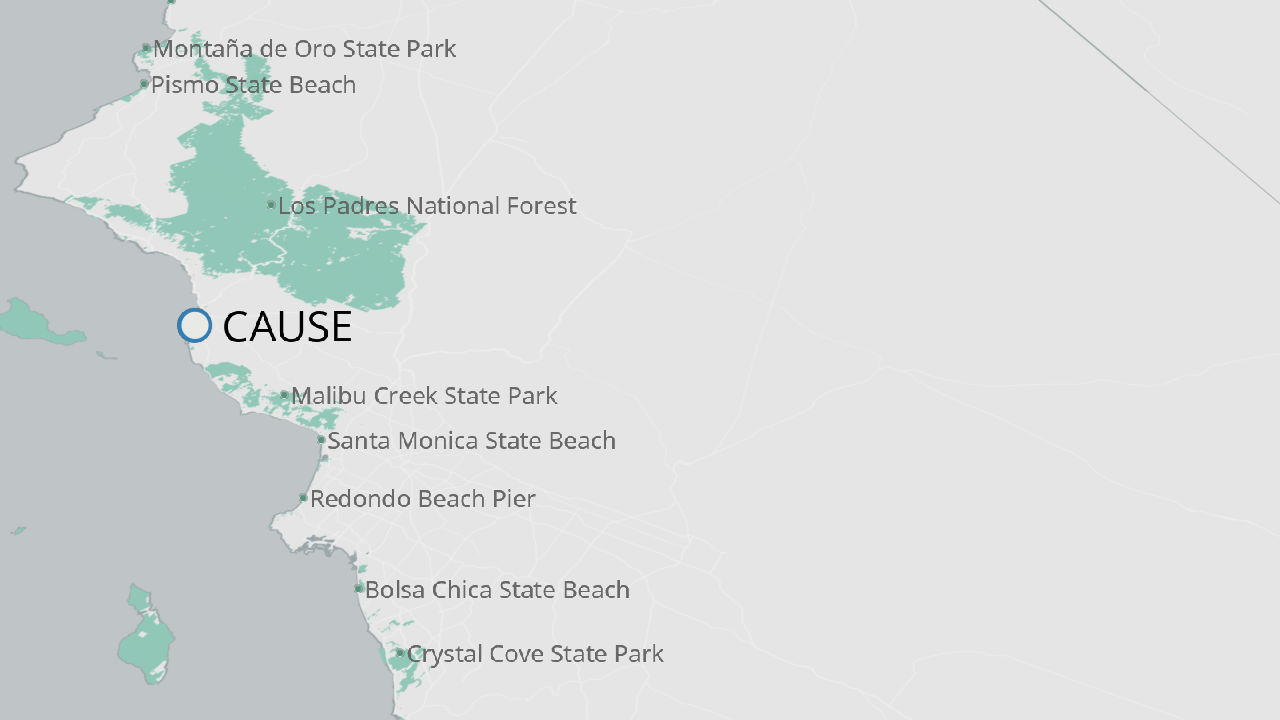

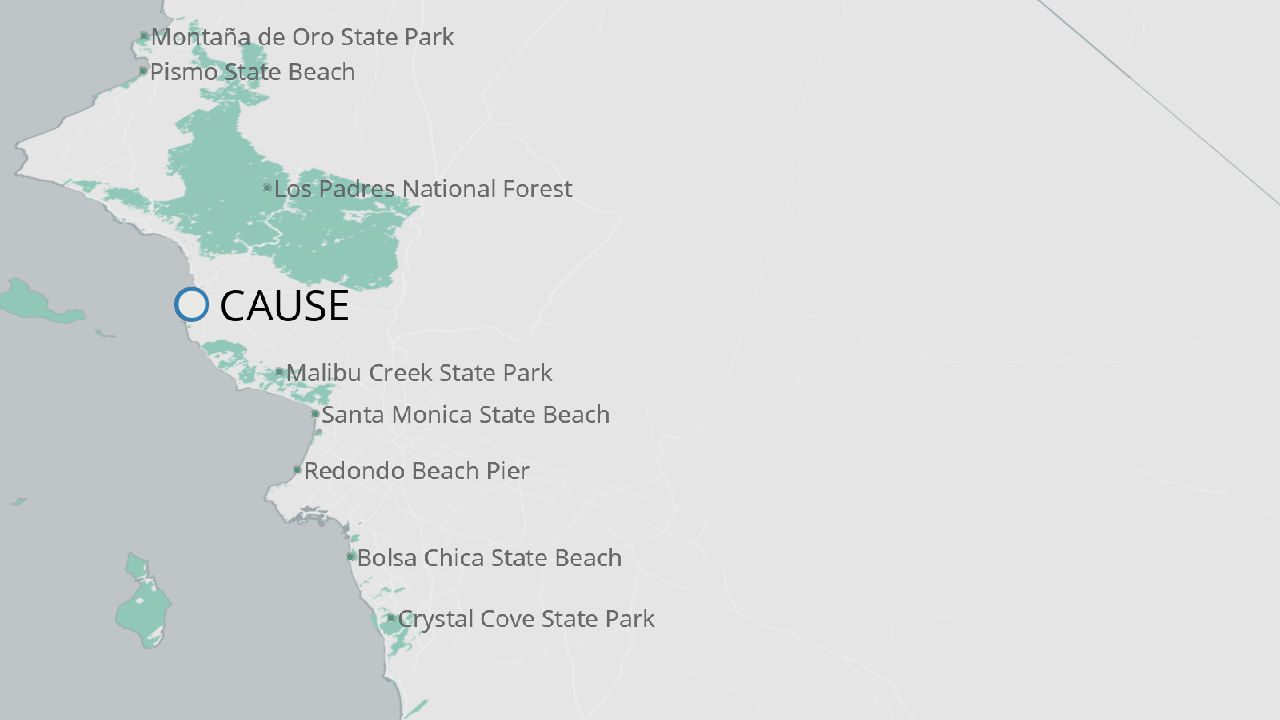

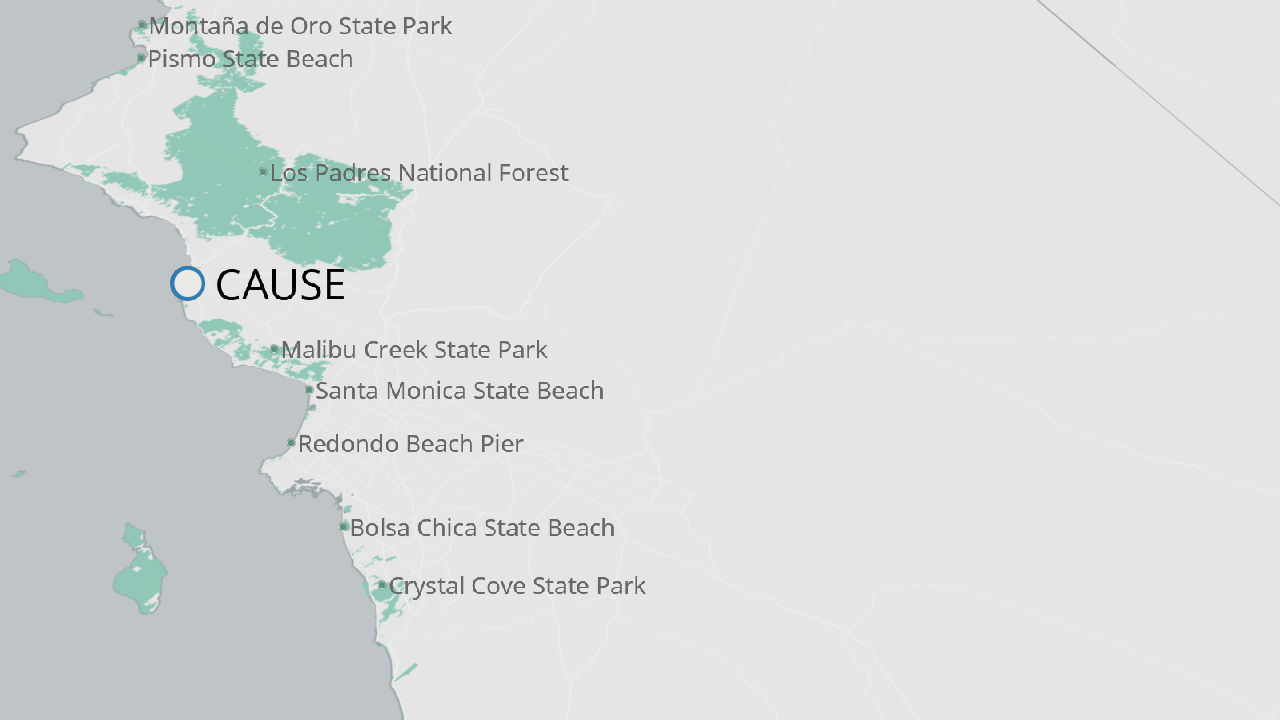

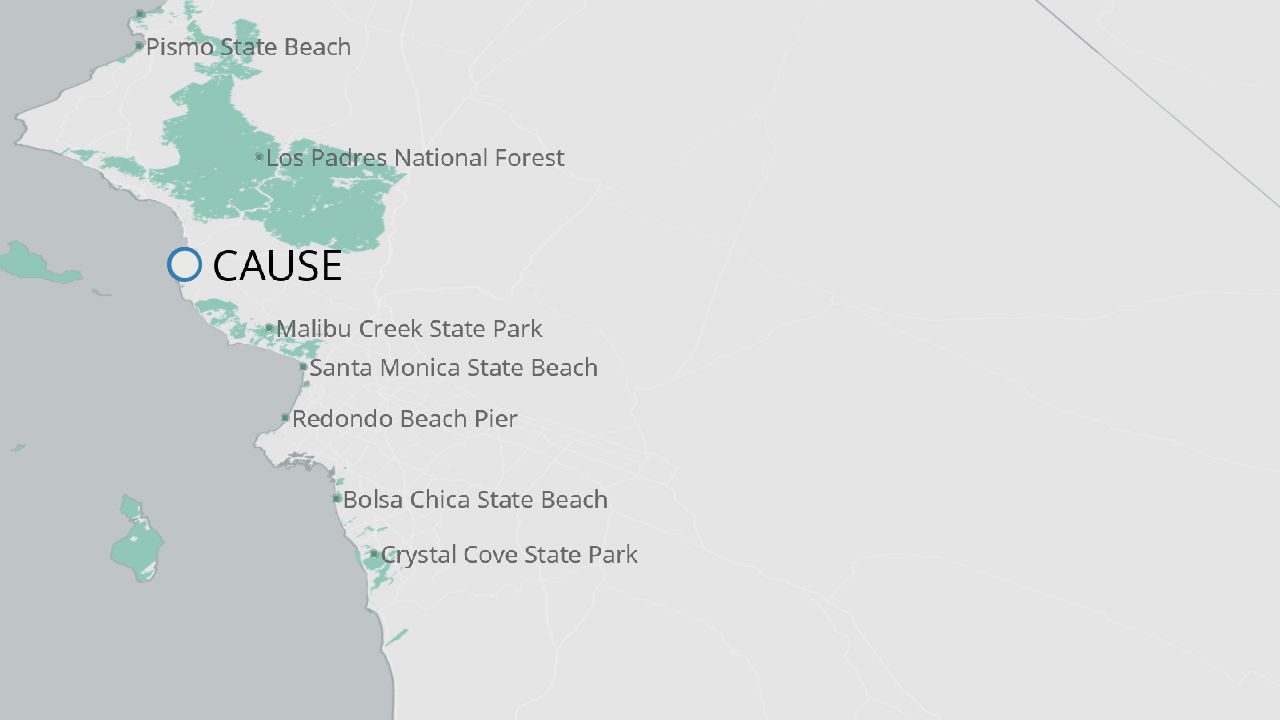

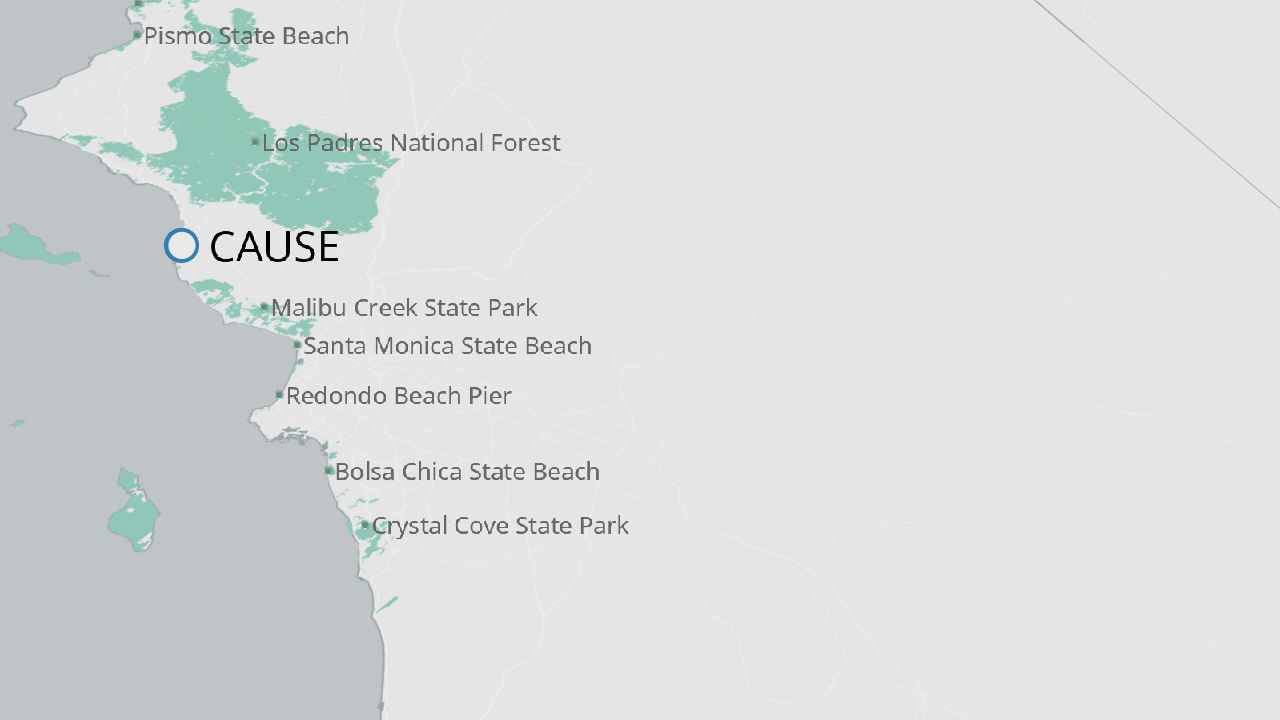

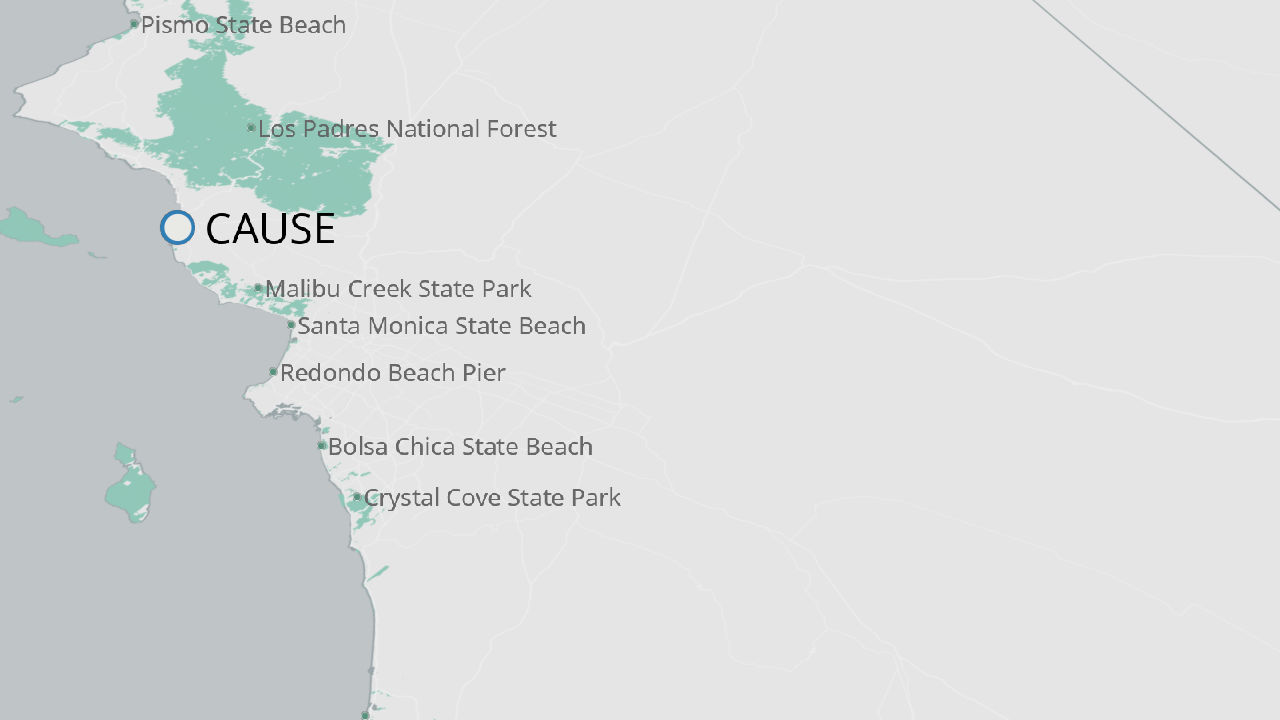

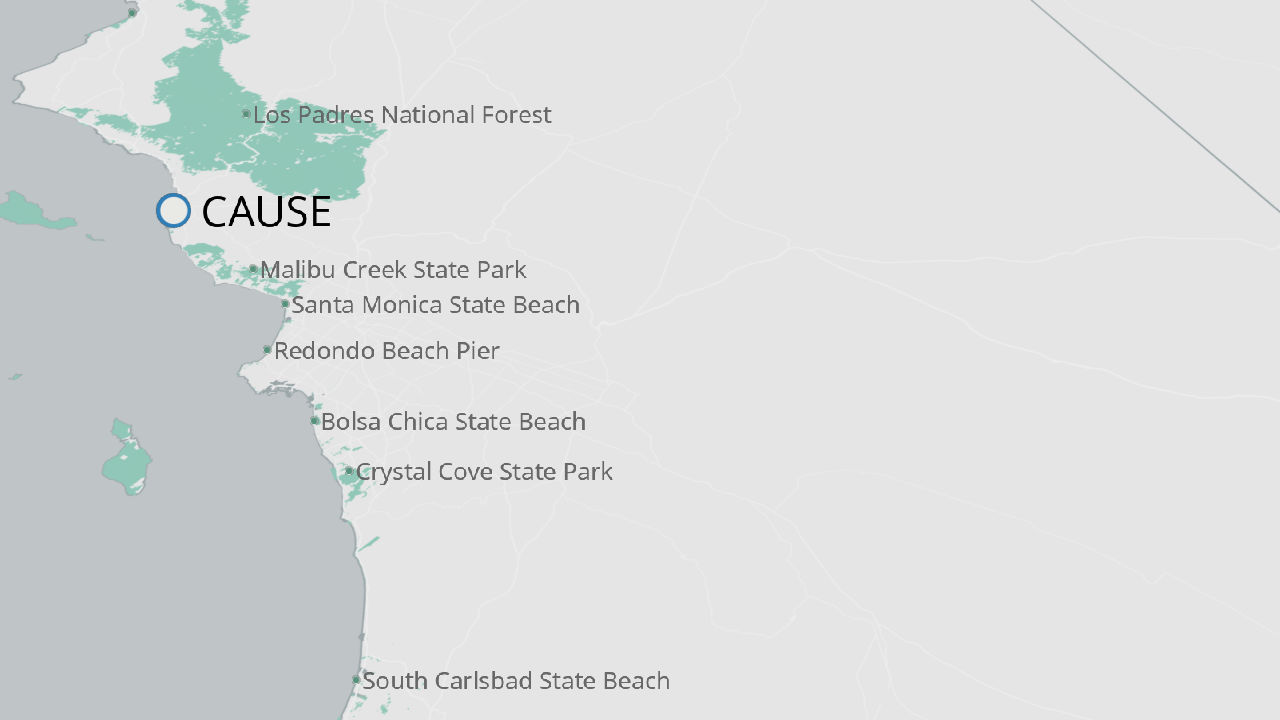

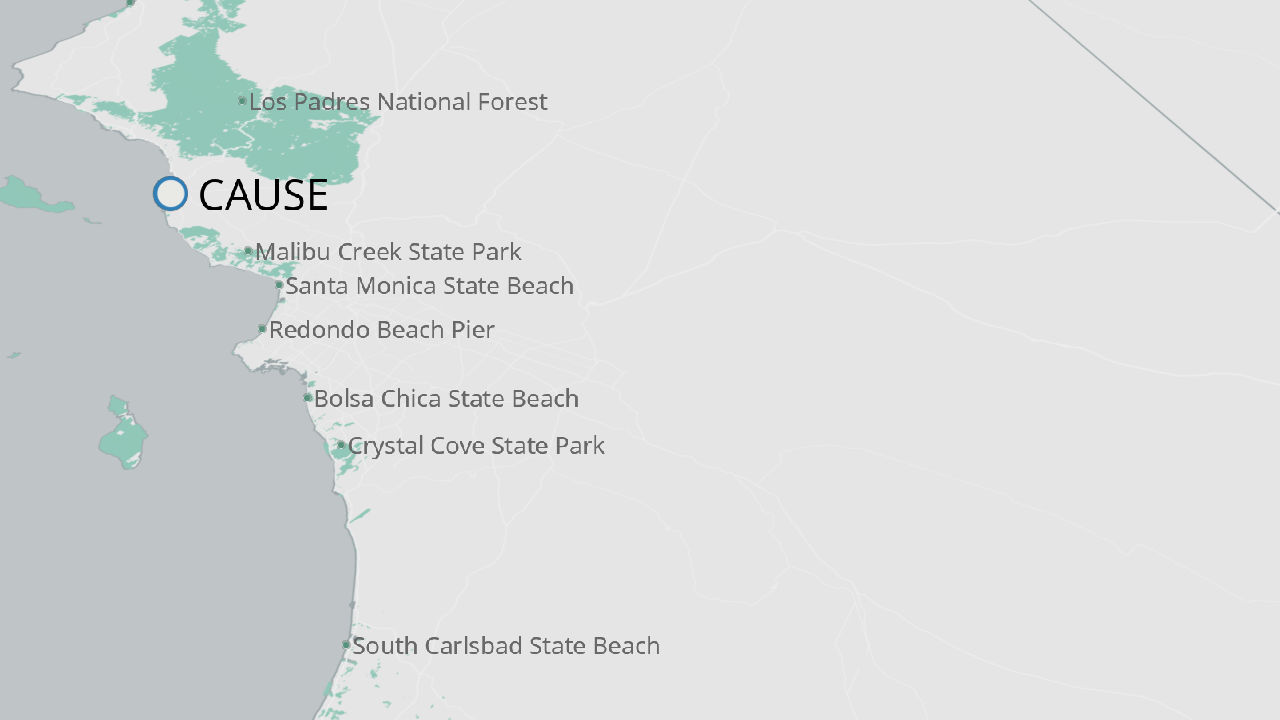

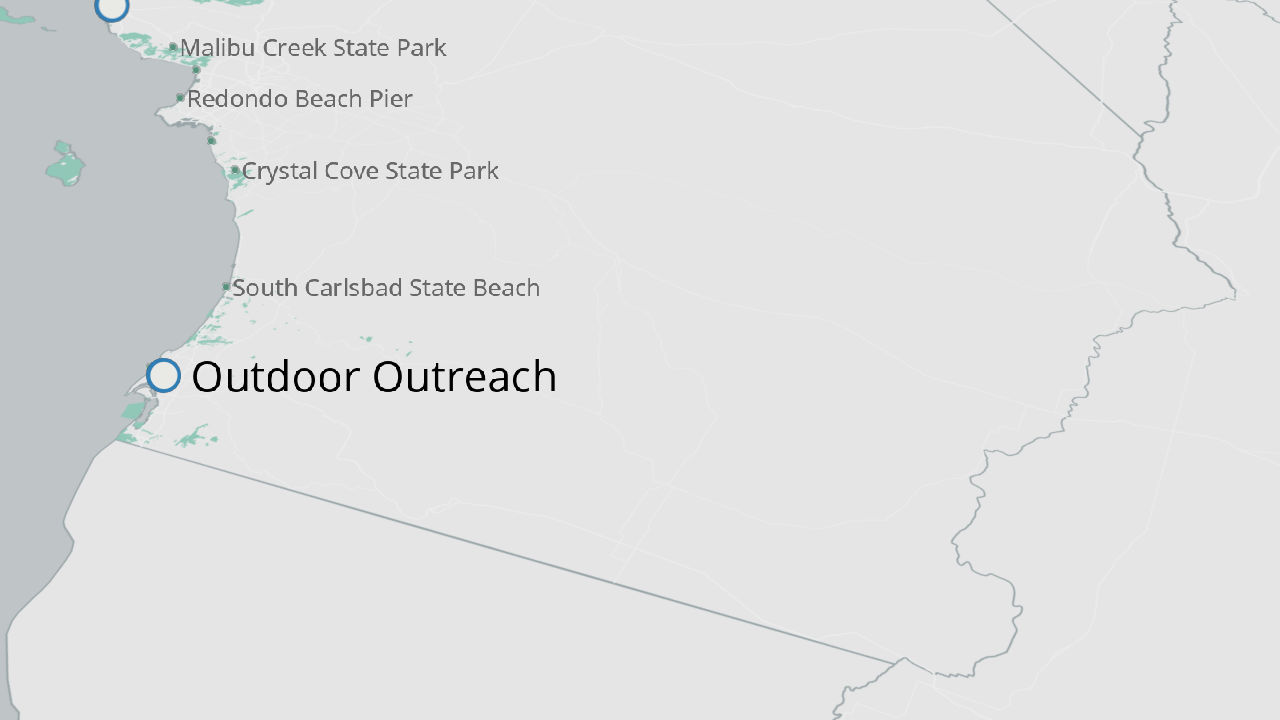

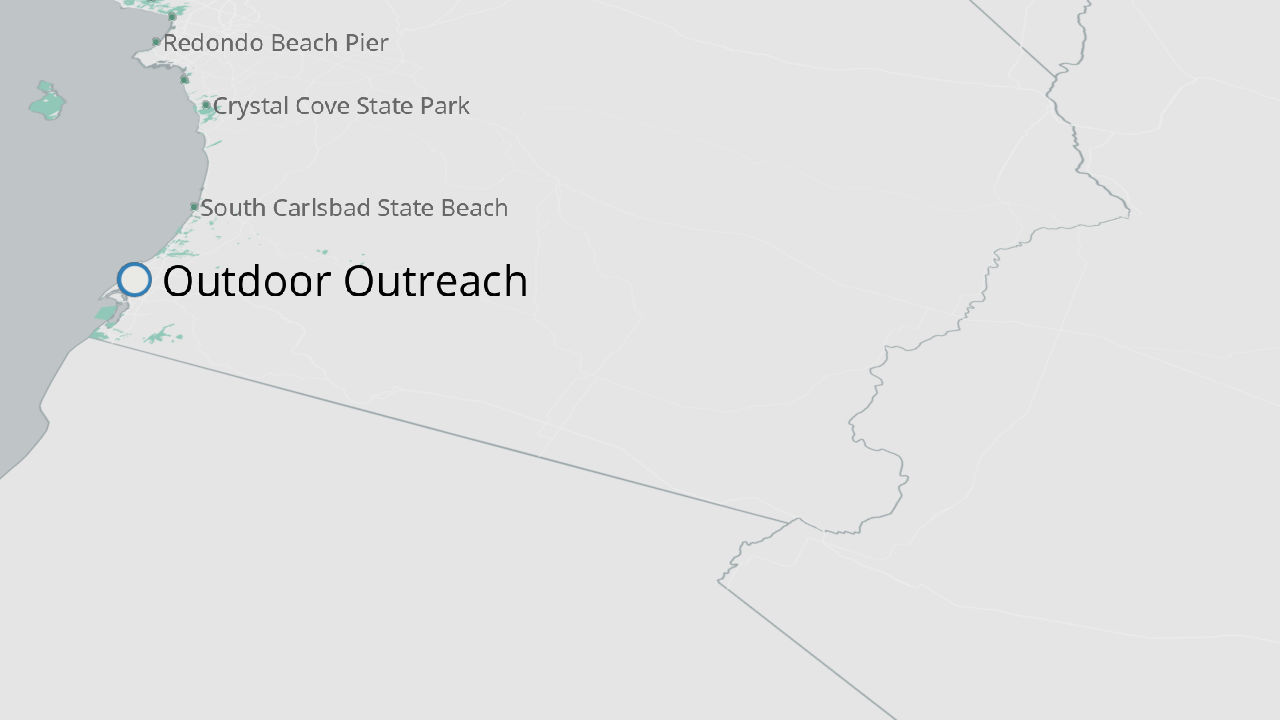

Beaches Are Among California's Most Popular Parks

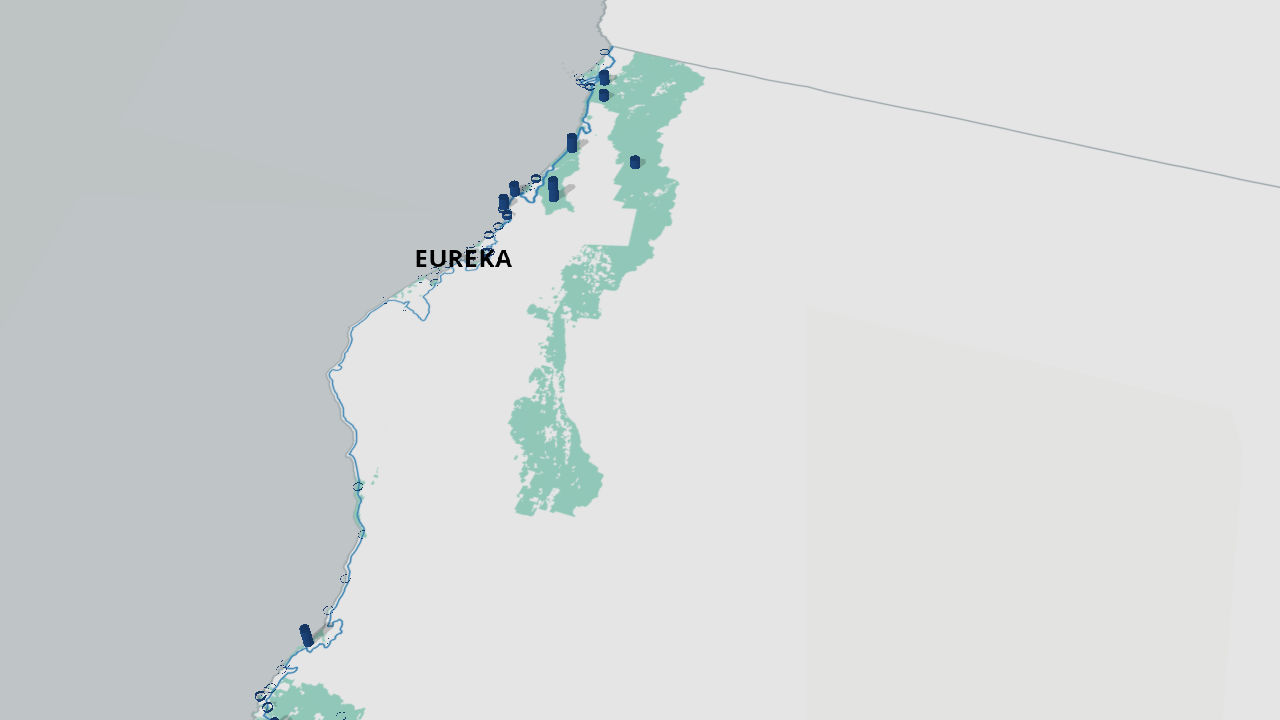

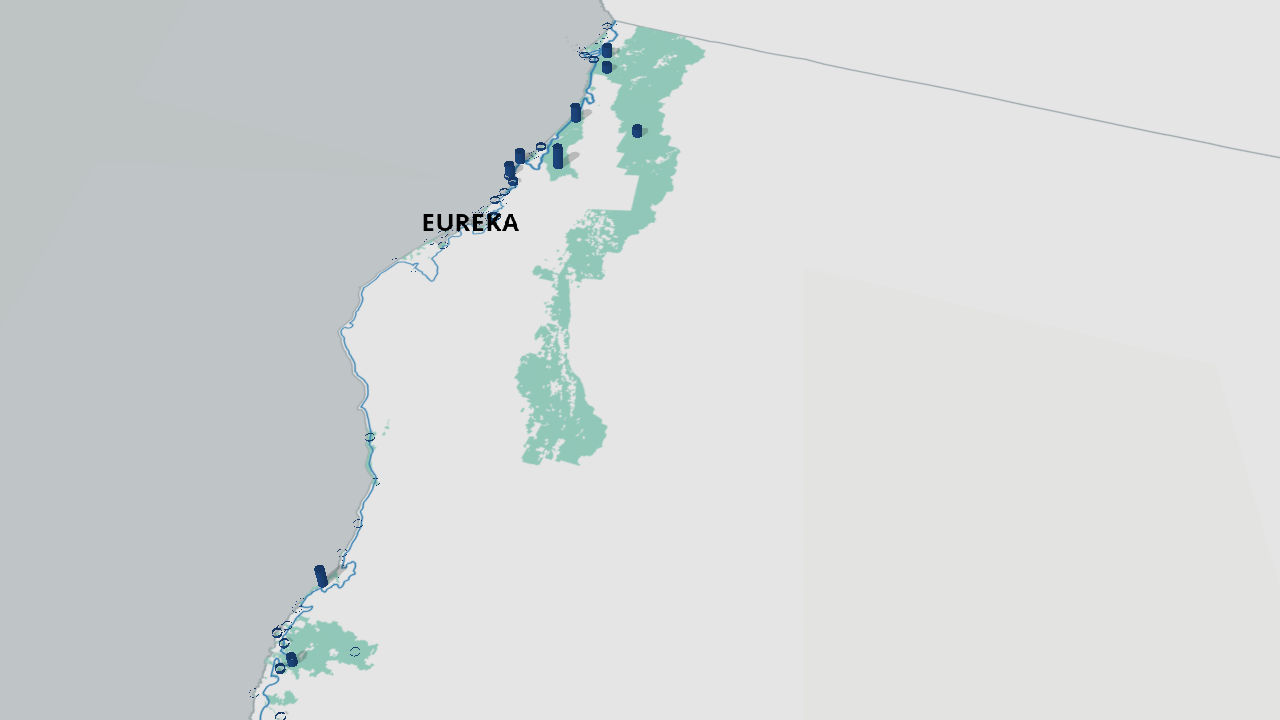

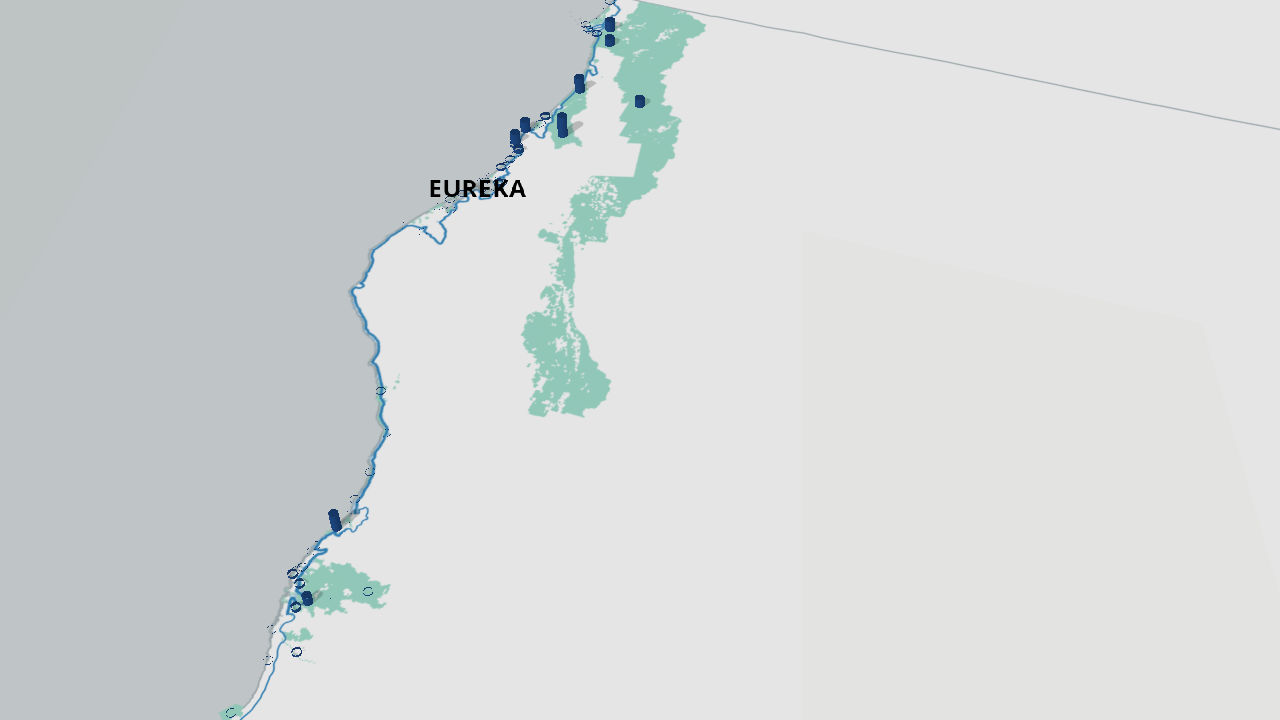

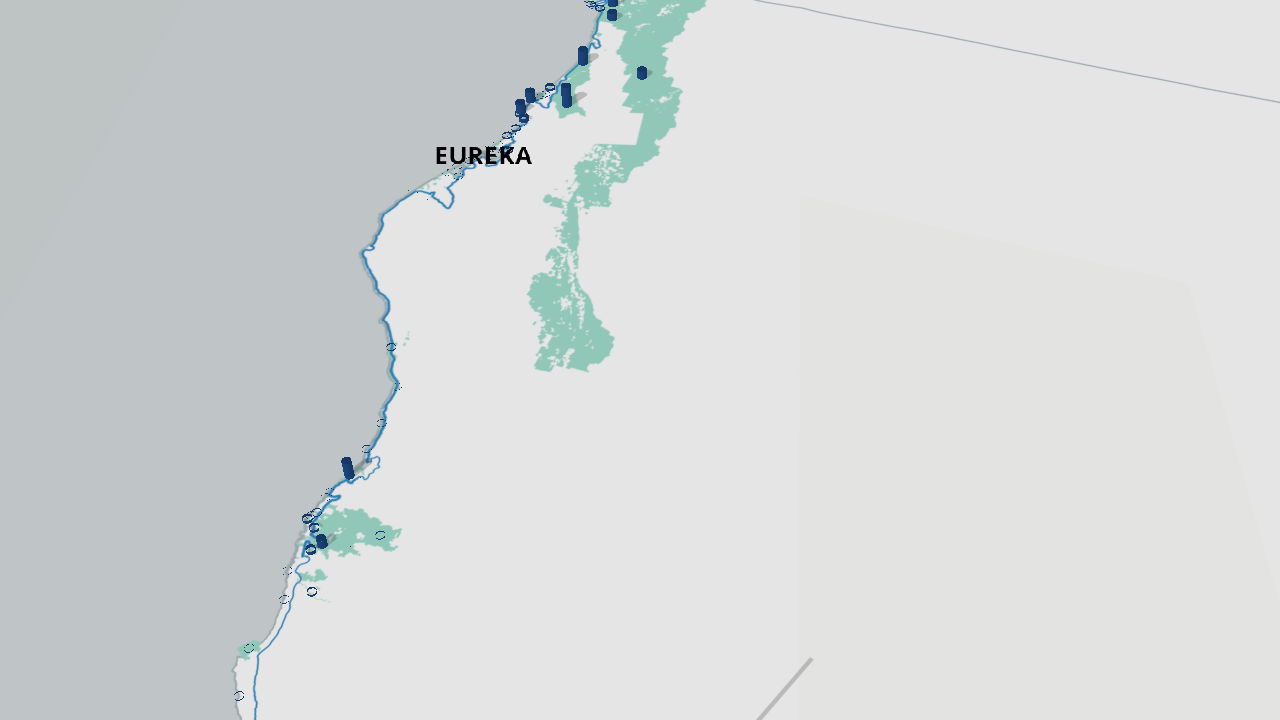

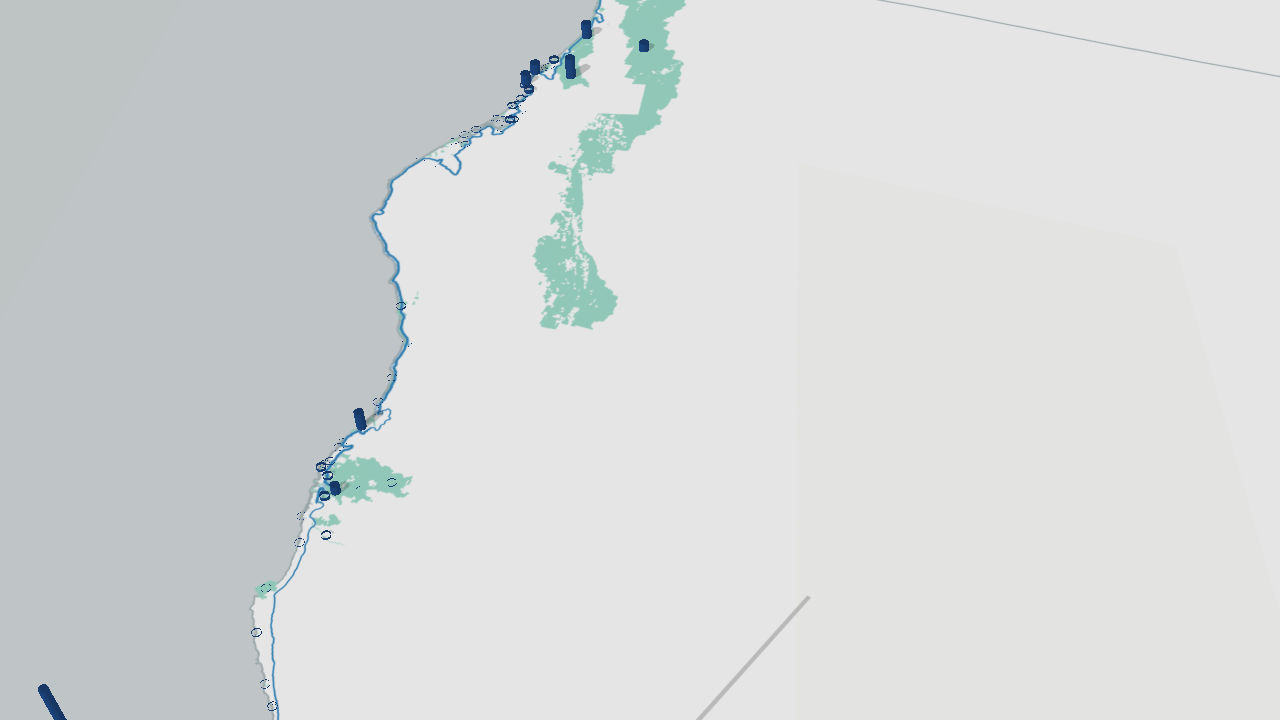

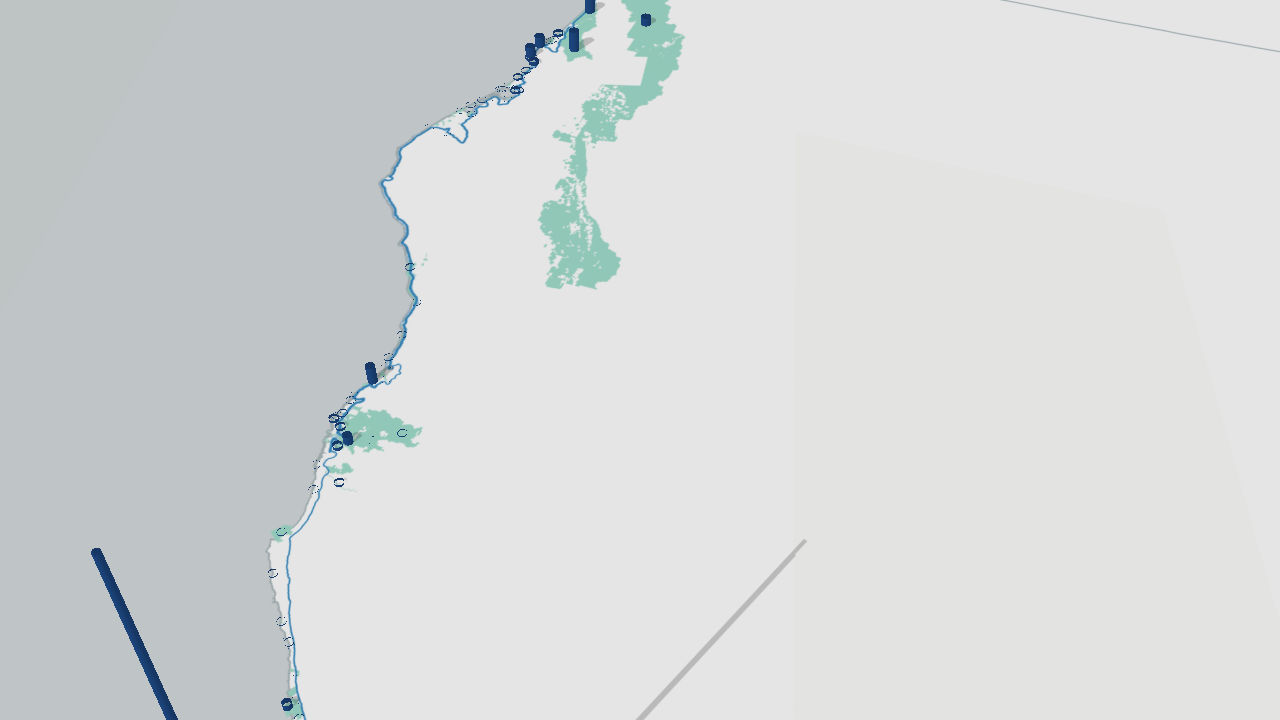

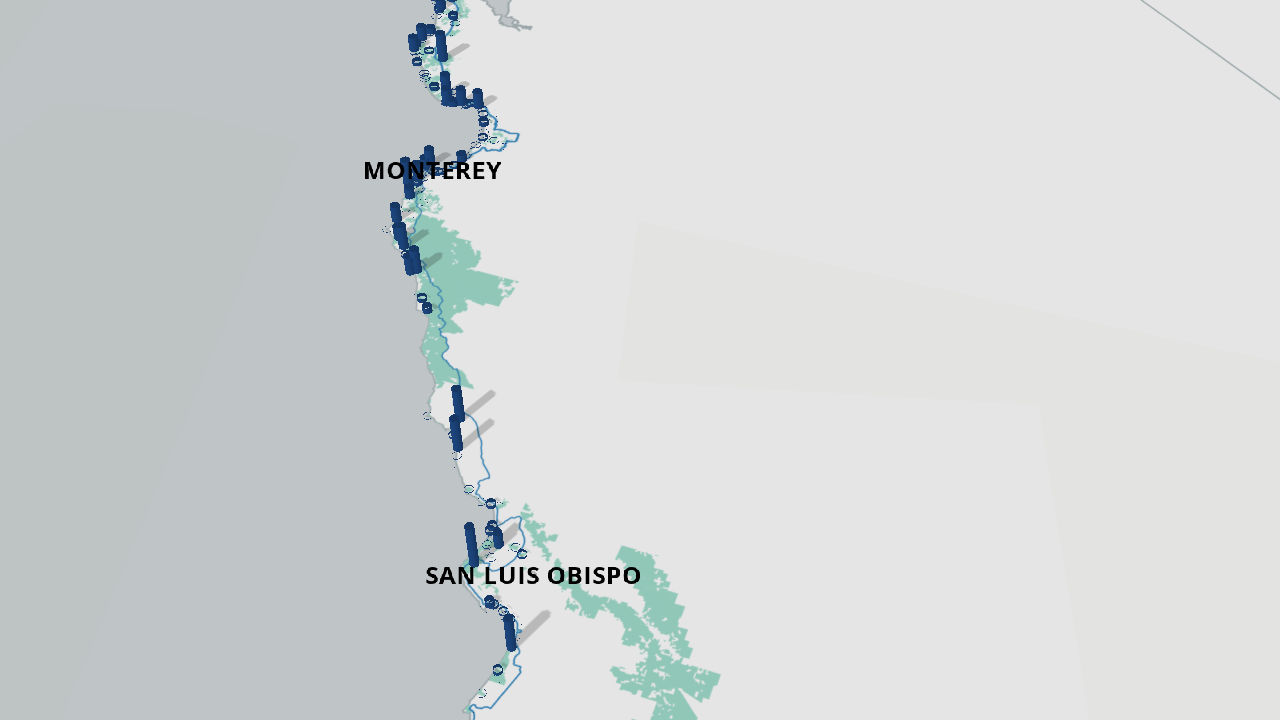

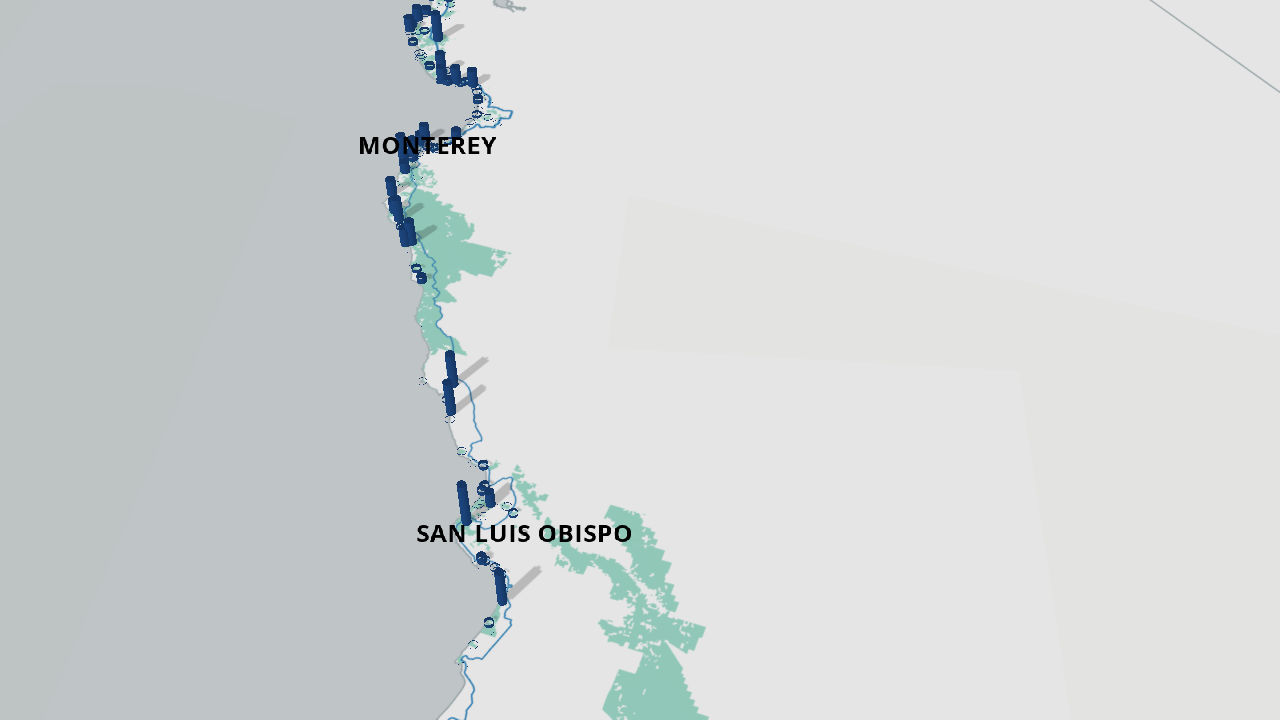

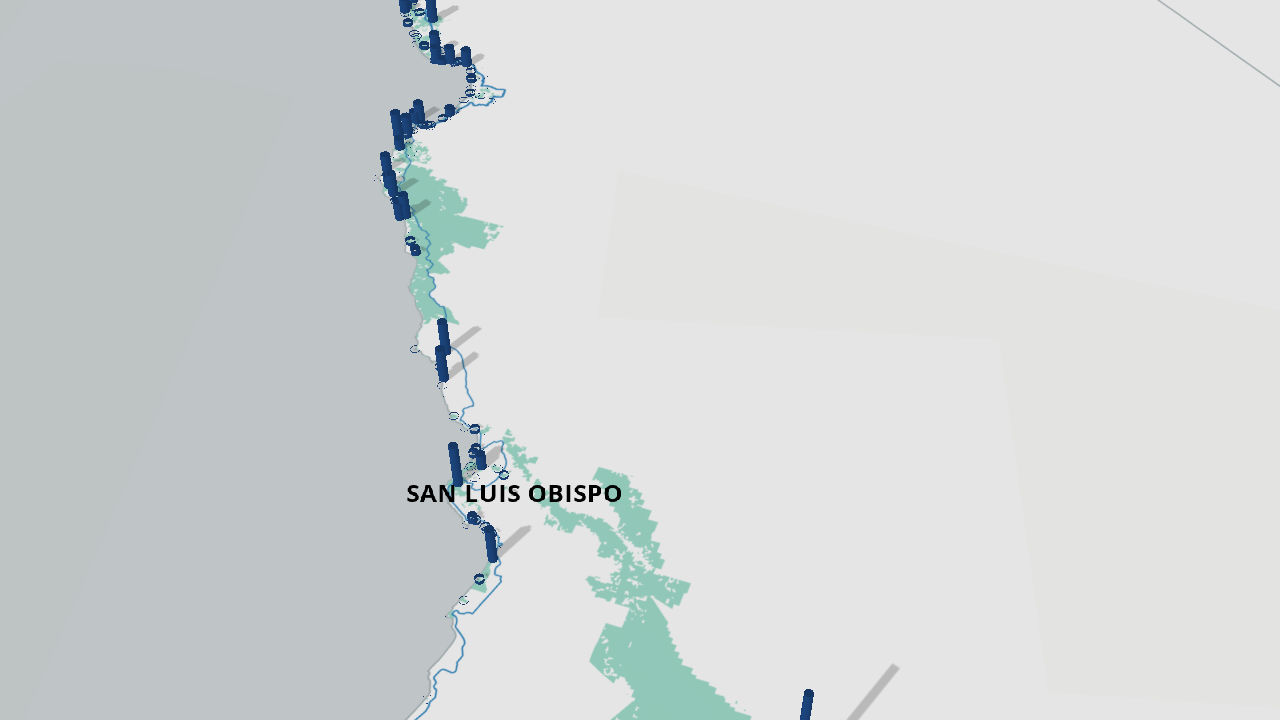

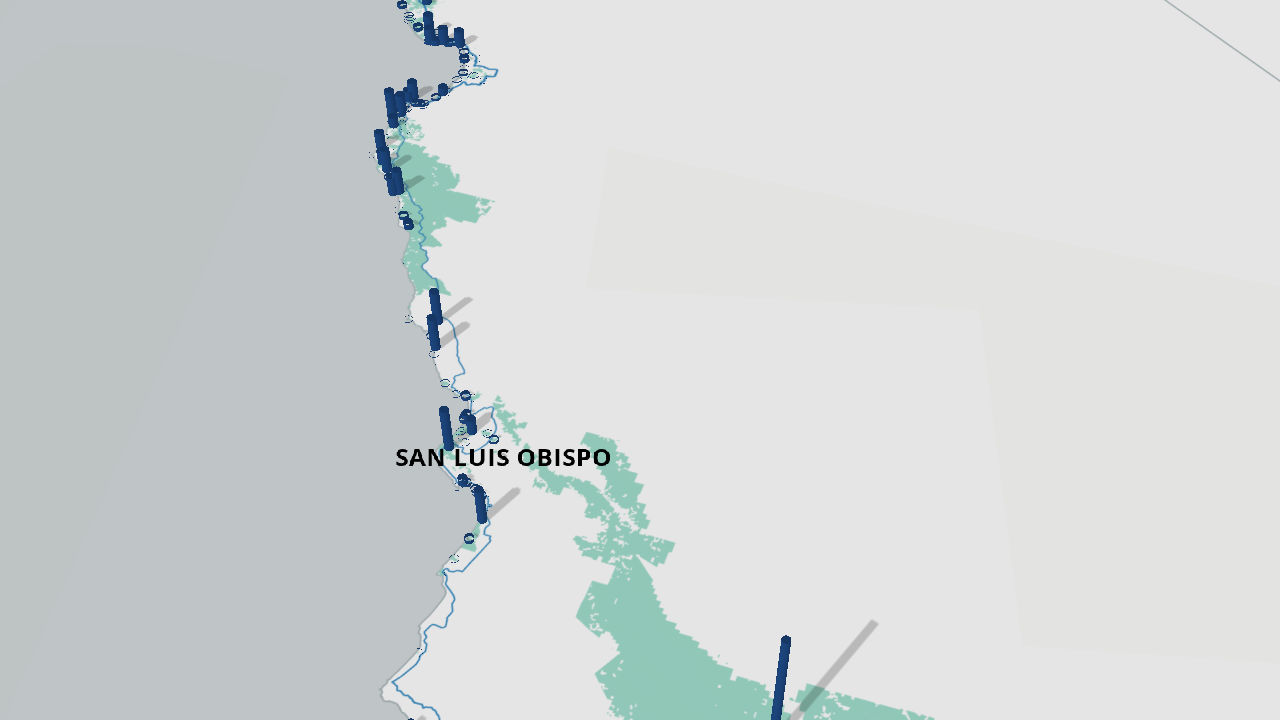

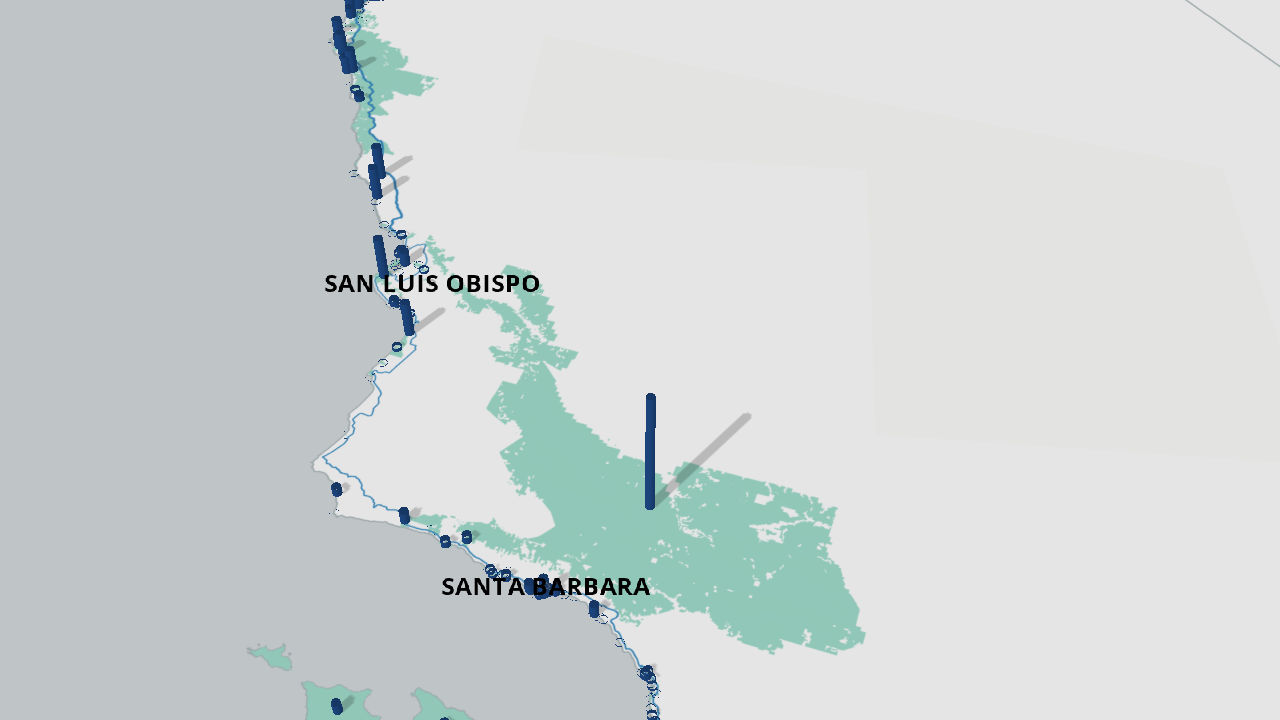

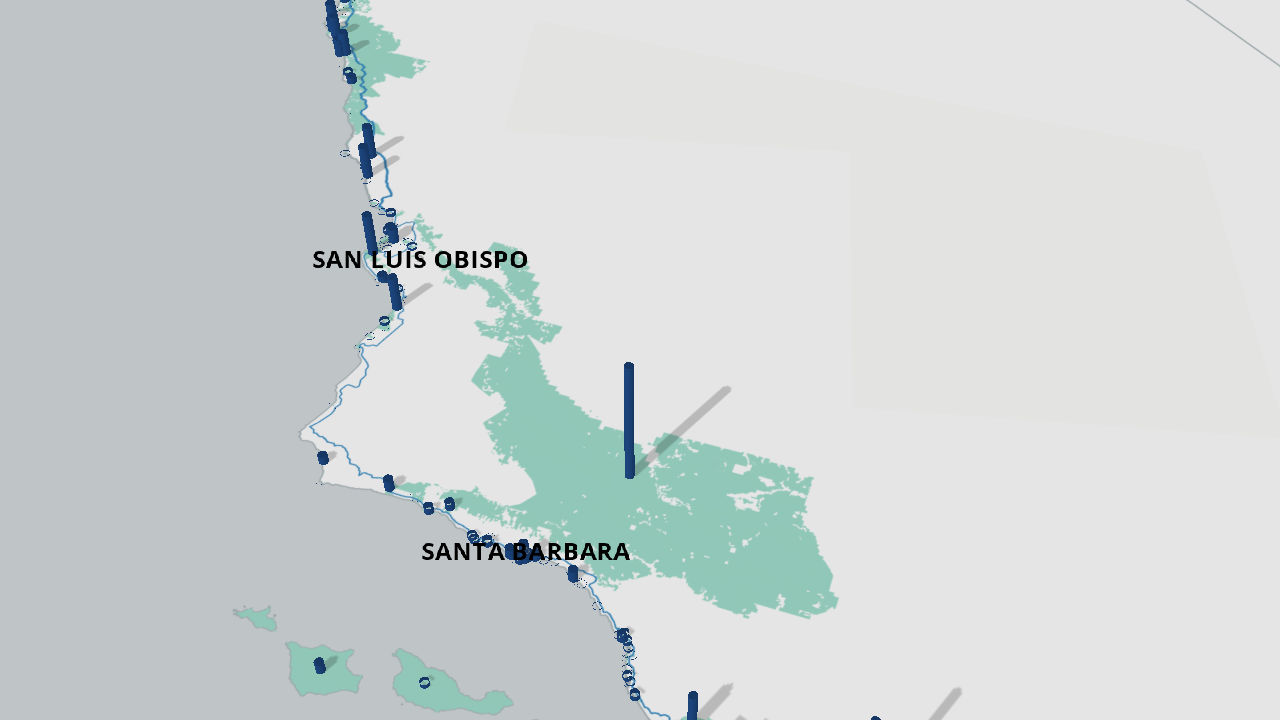

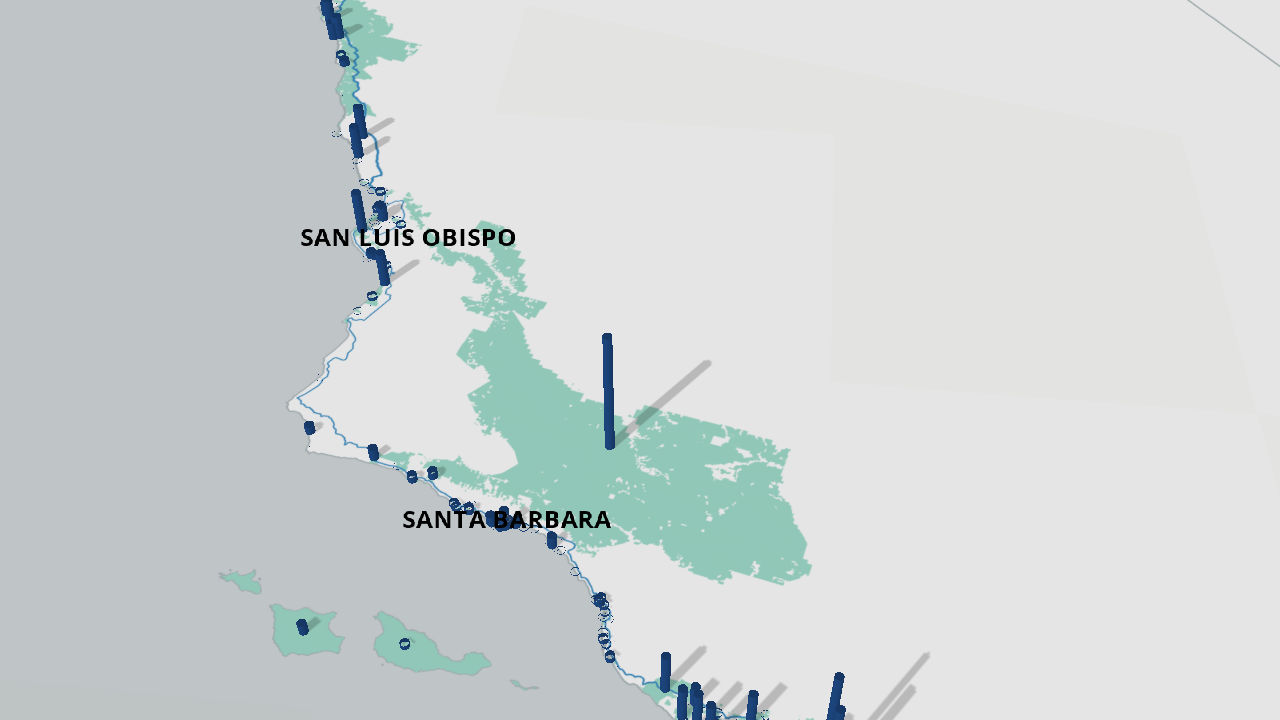

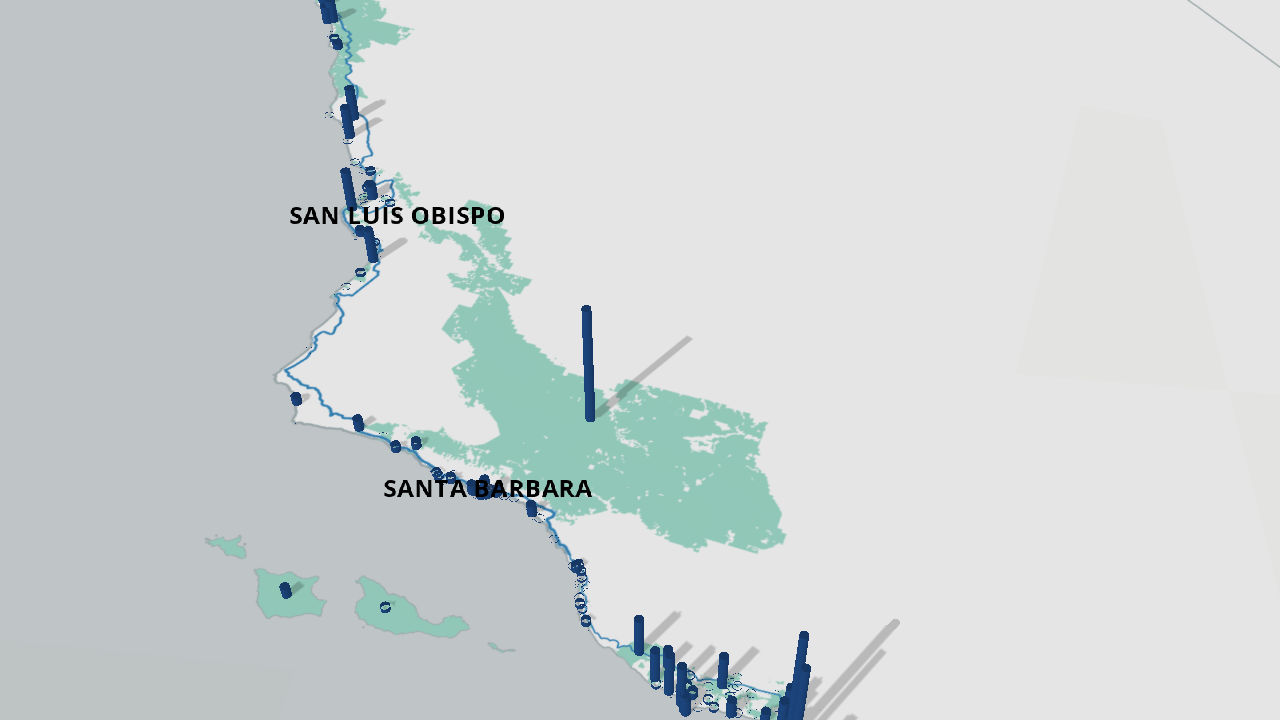

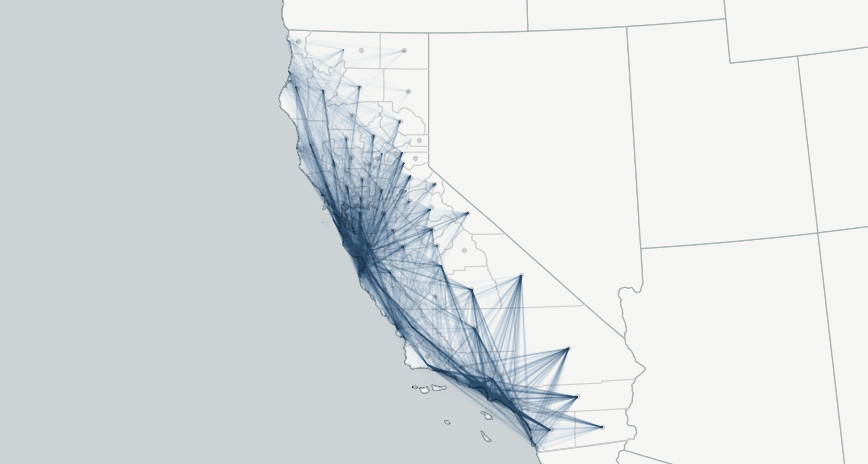

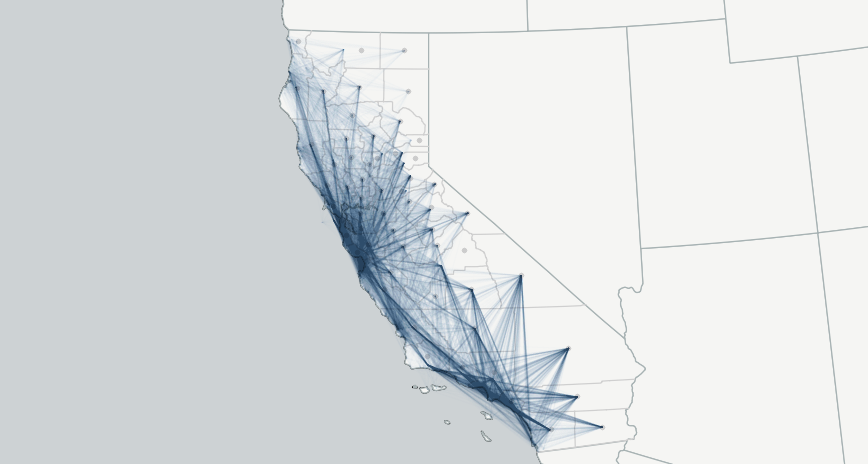

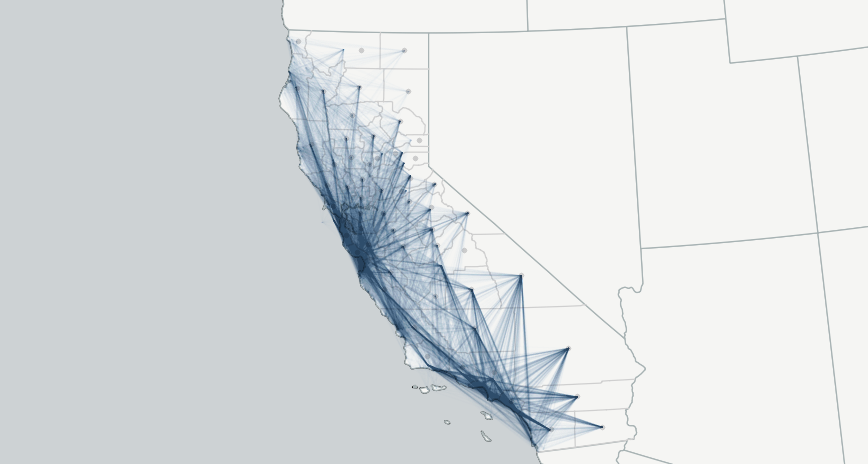

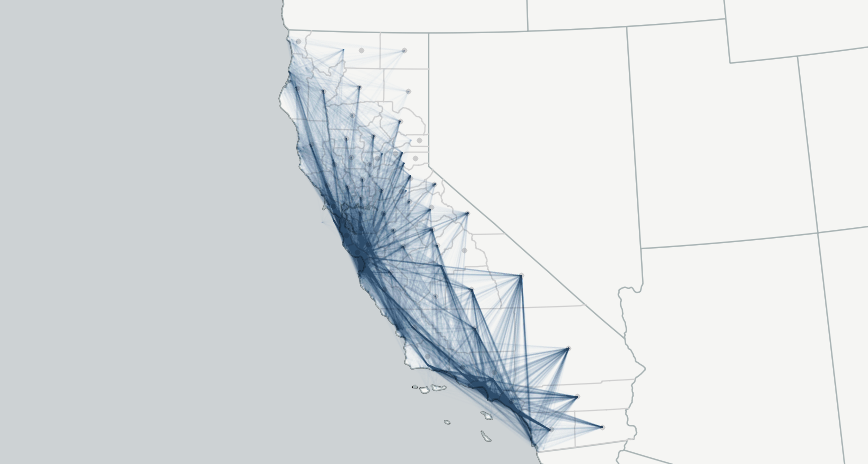

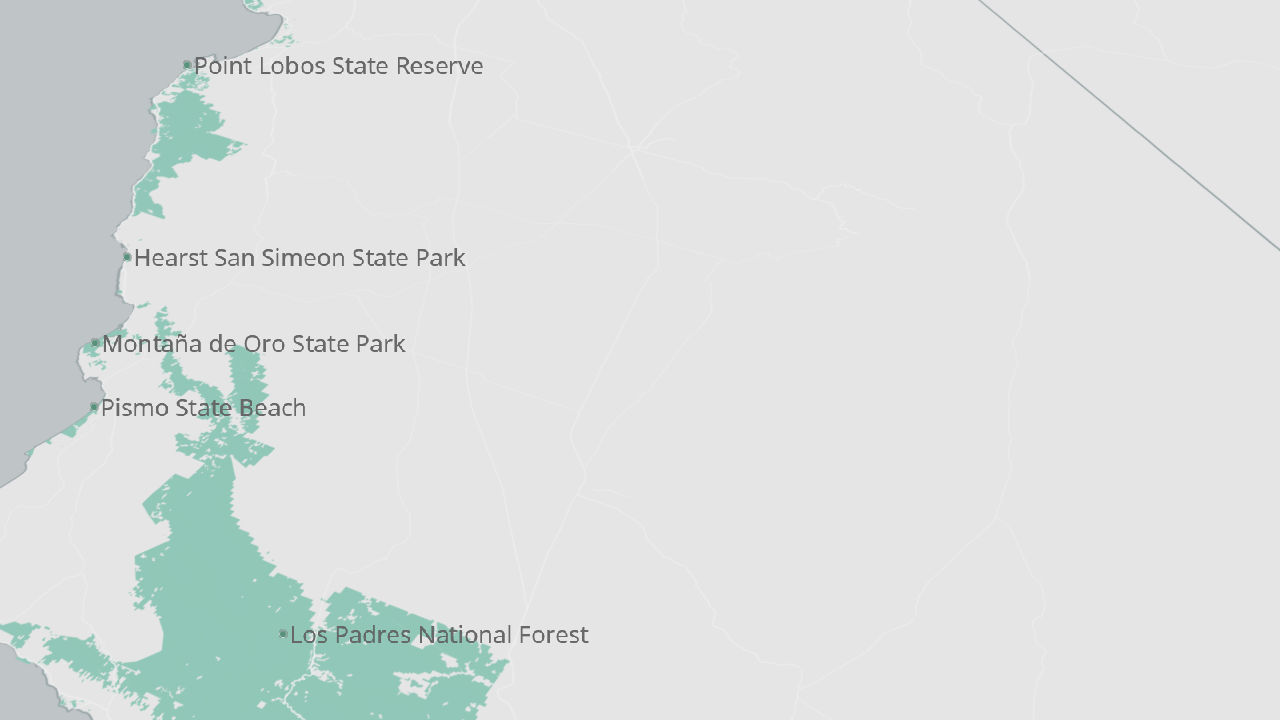

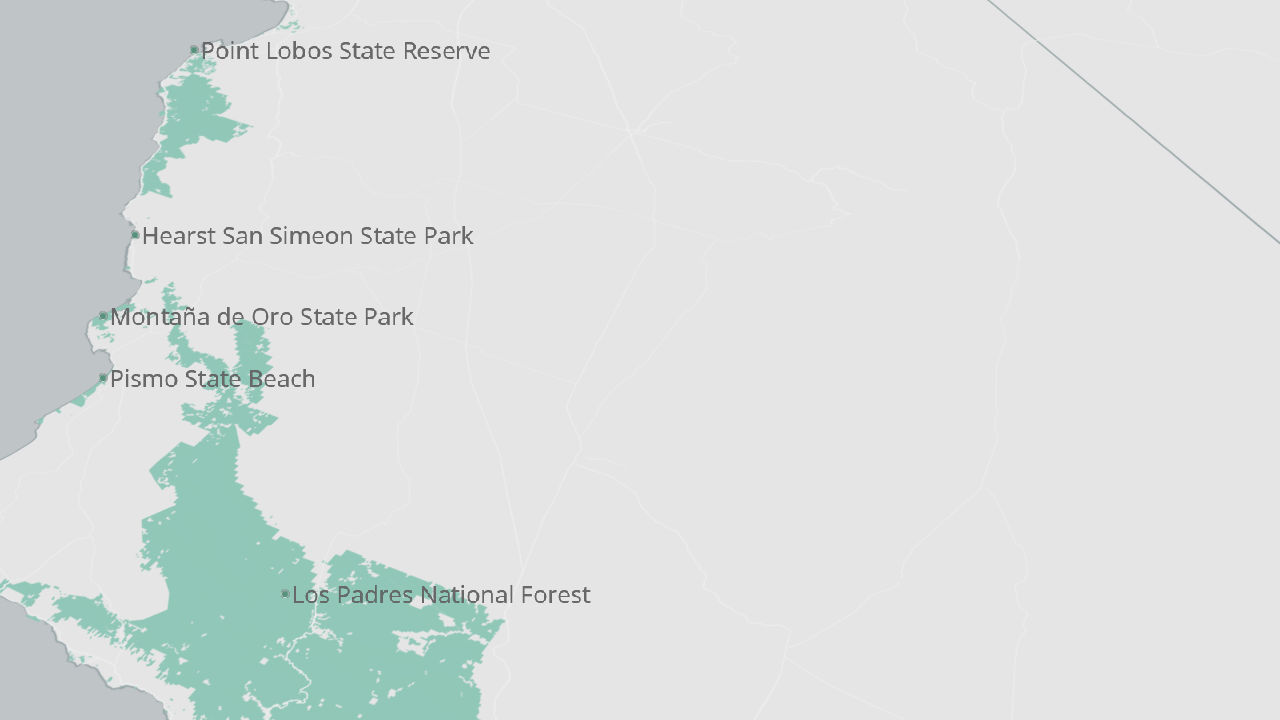

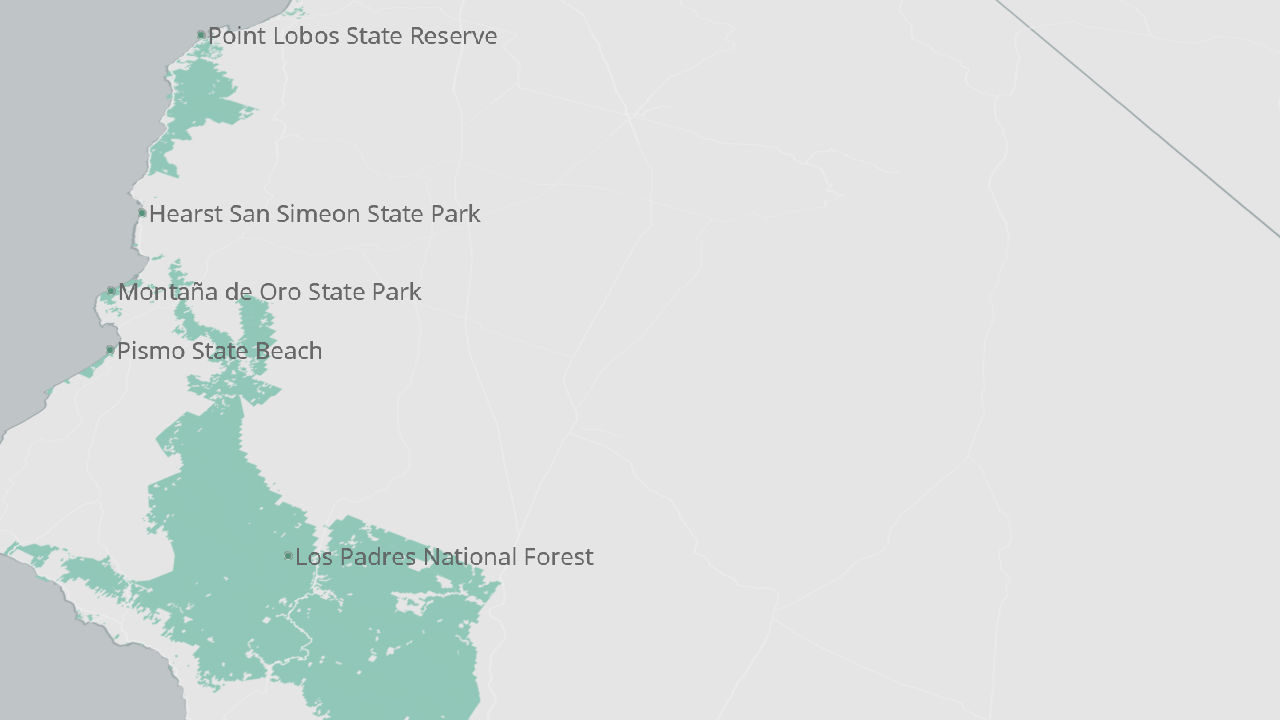

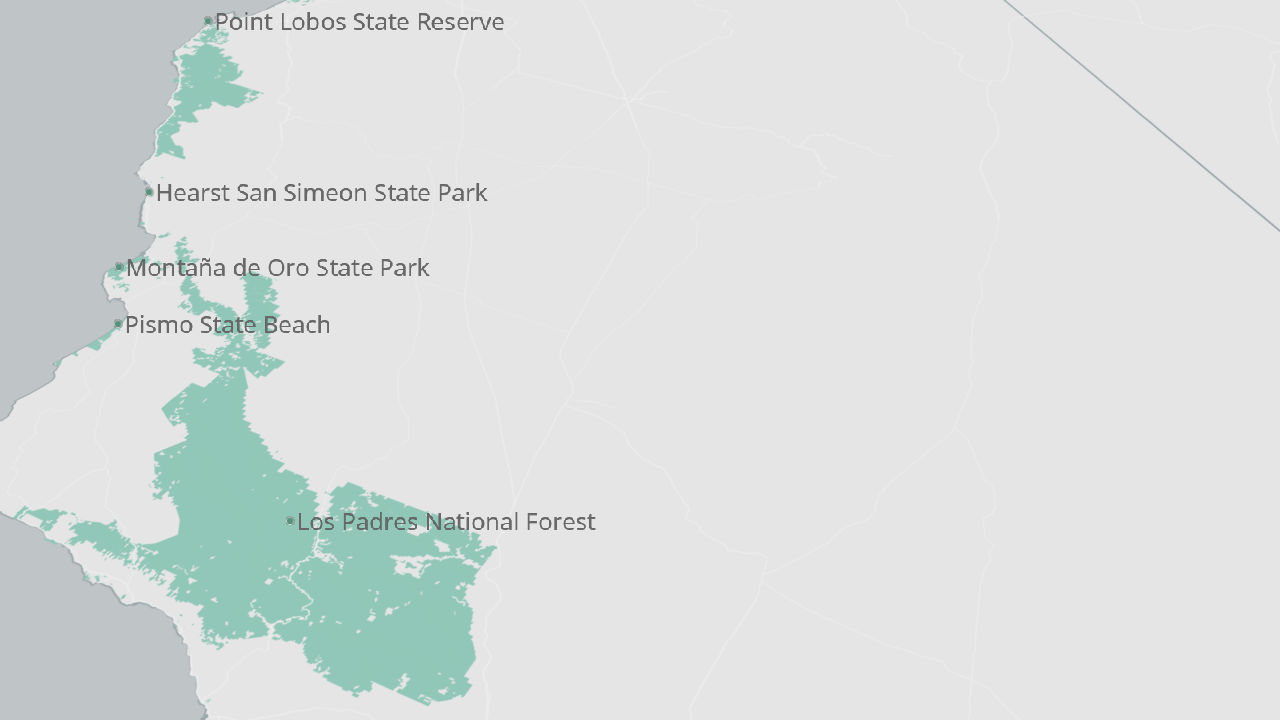

California's public beaches and coastal parks are among the most popular public parks in the state. This map shows relative visitation rates to all of California's local, regional, state, and national parks—along the coast and inland—which we estimated based on Instagram users who post photos from these parks and beaches. High rates of visitation and sharing on social media show that the coast is a critically important part of California's system of parks and open spaces.

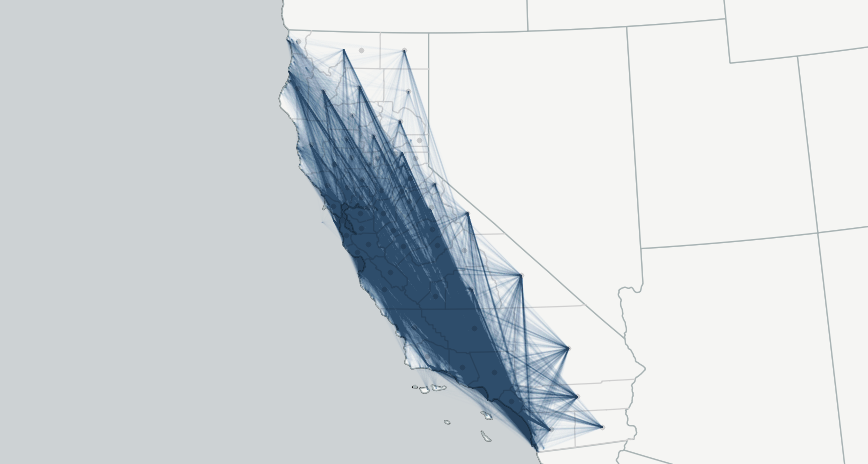

Coastal Park Visitation Rates

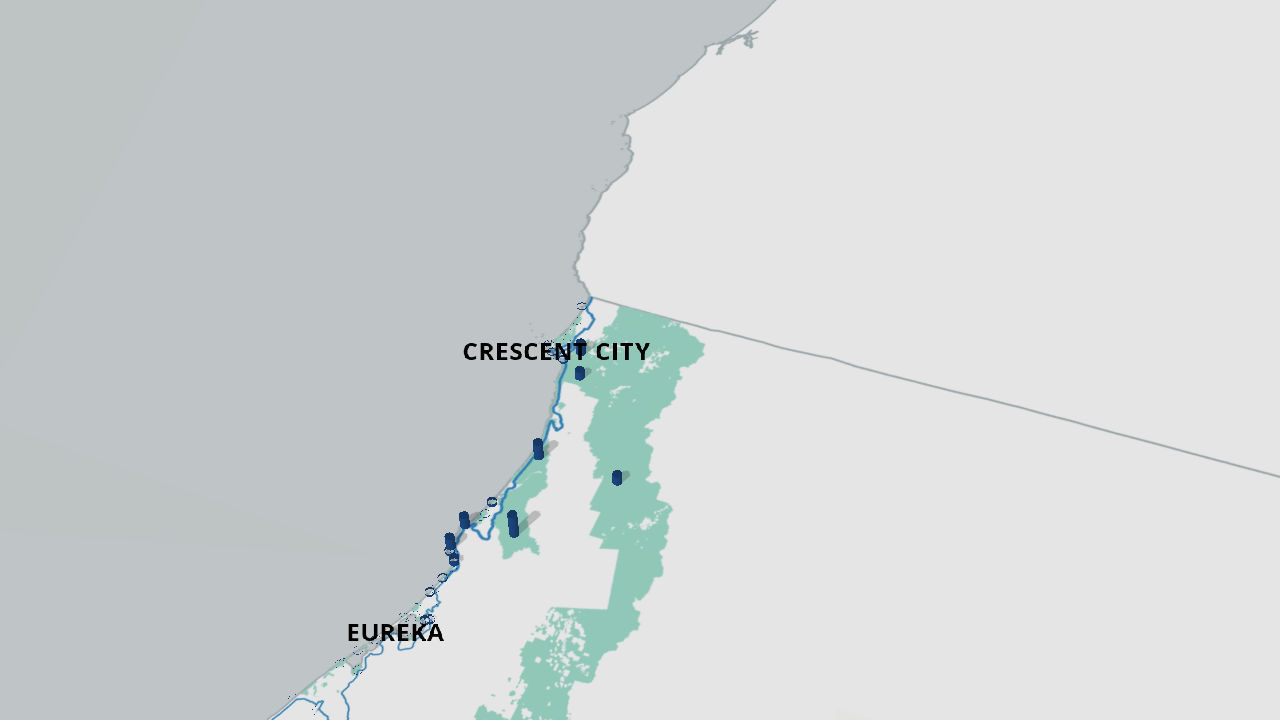

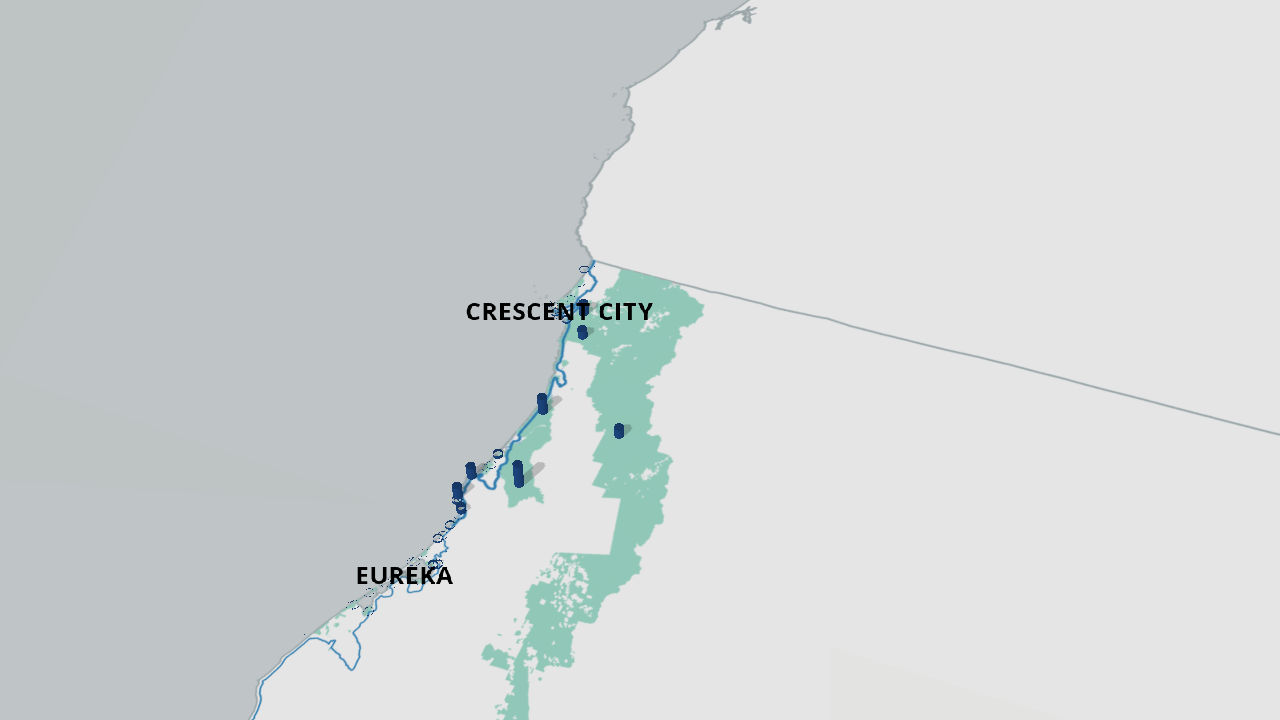

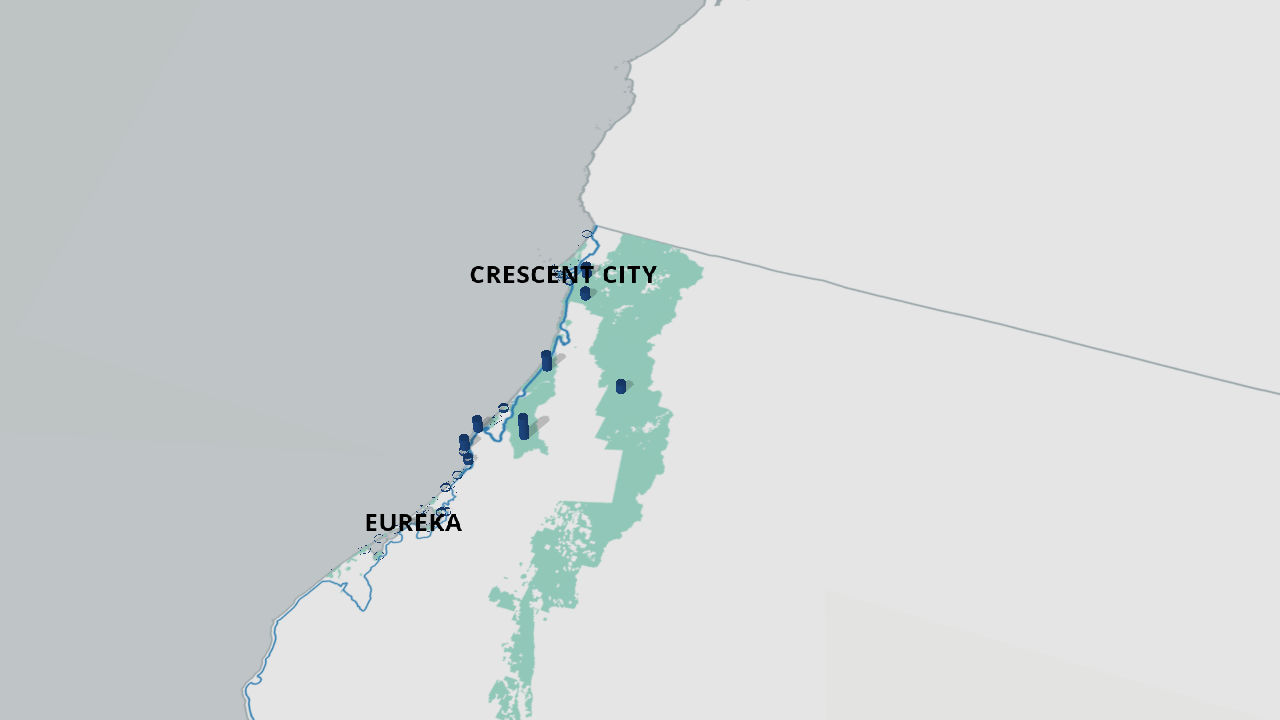

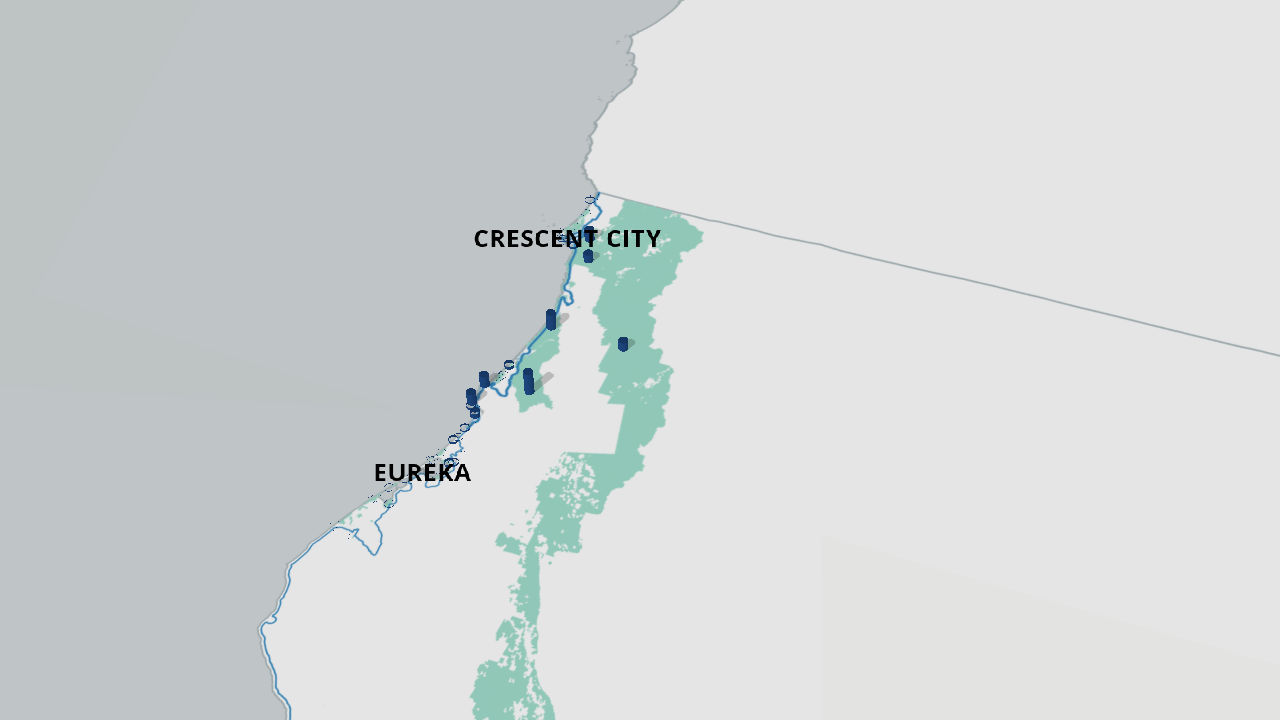

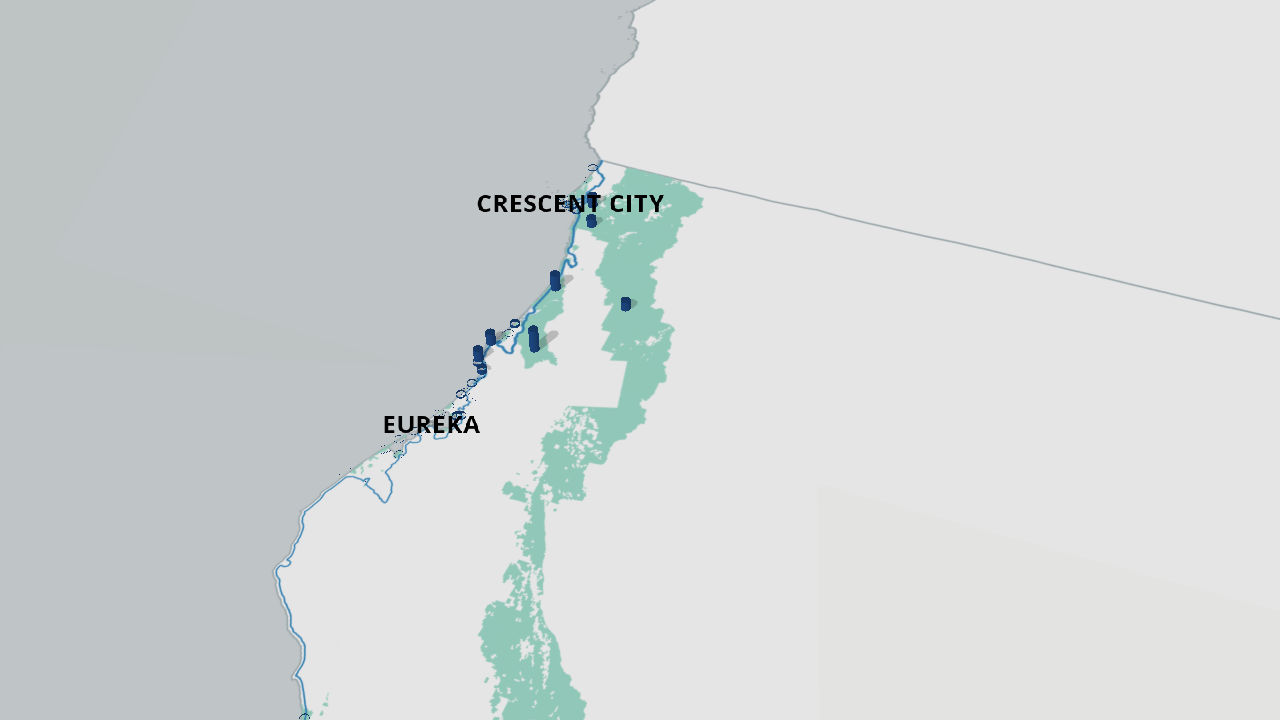

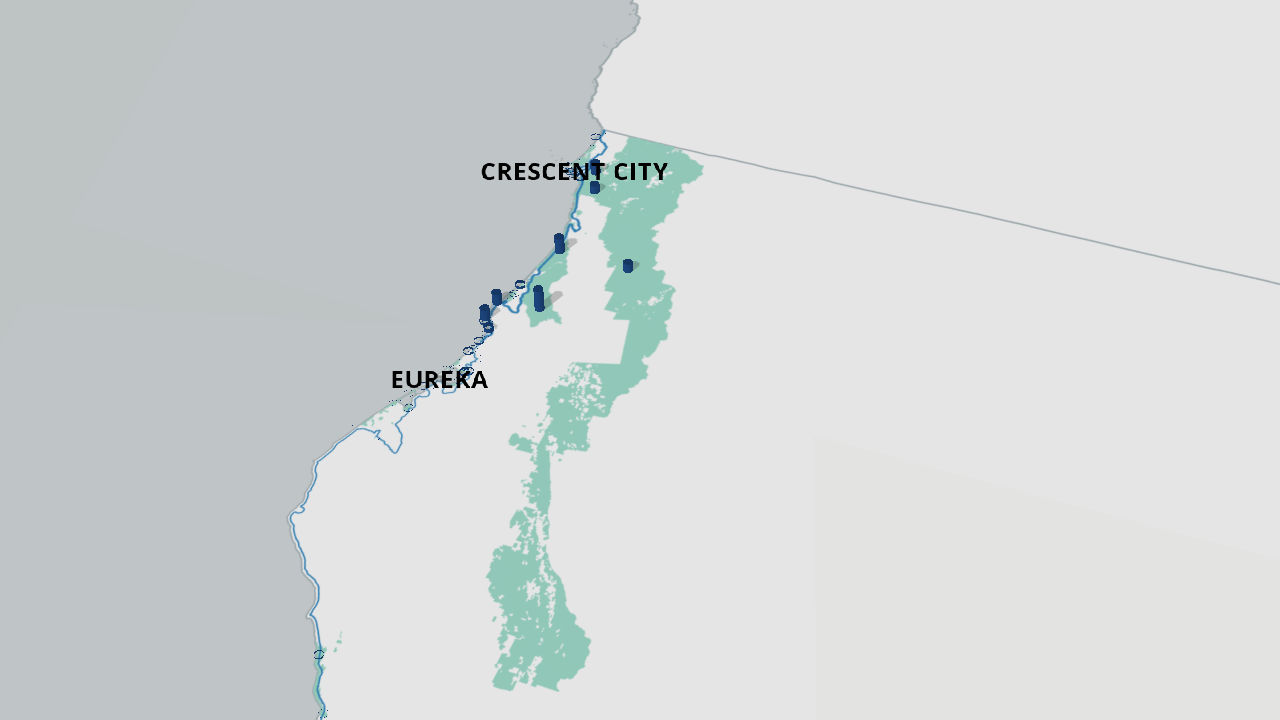

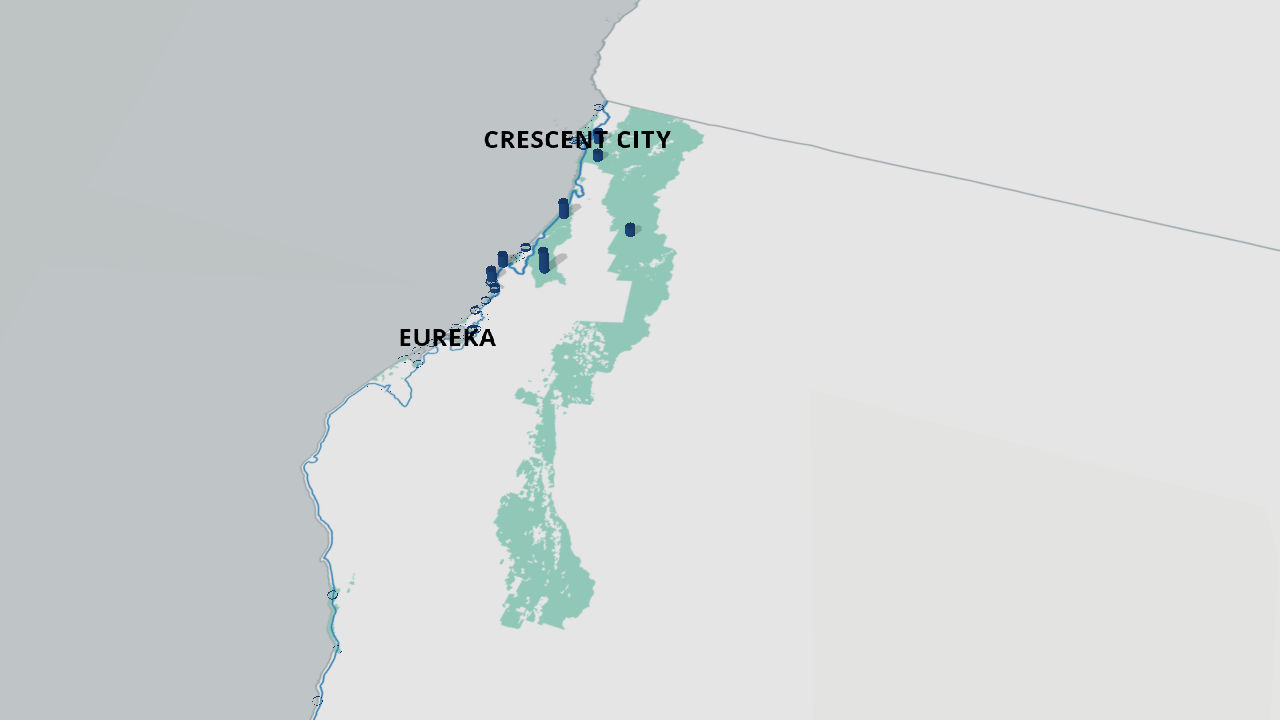

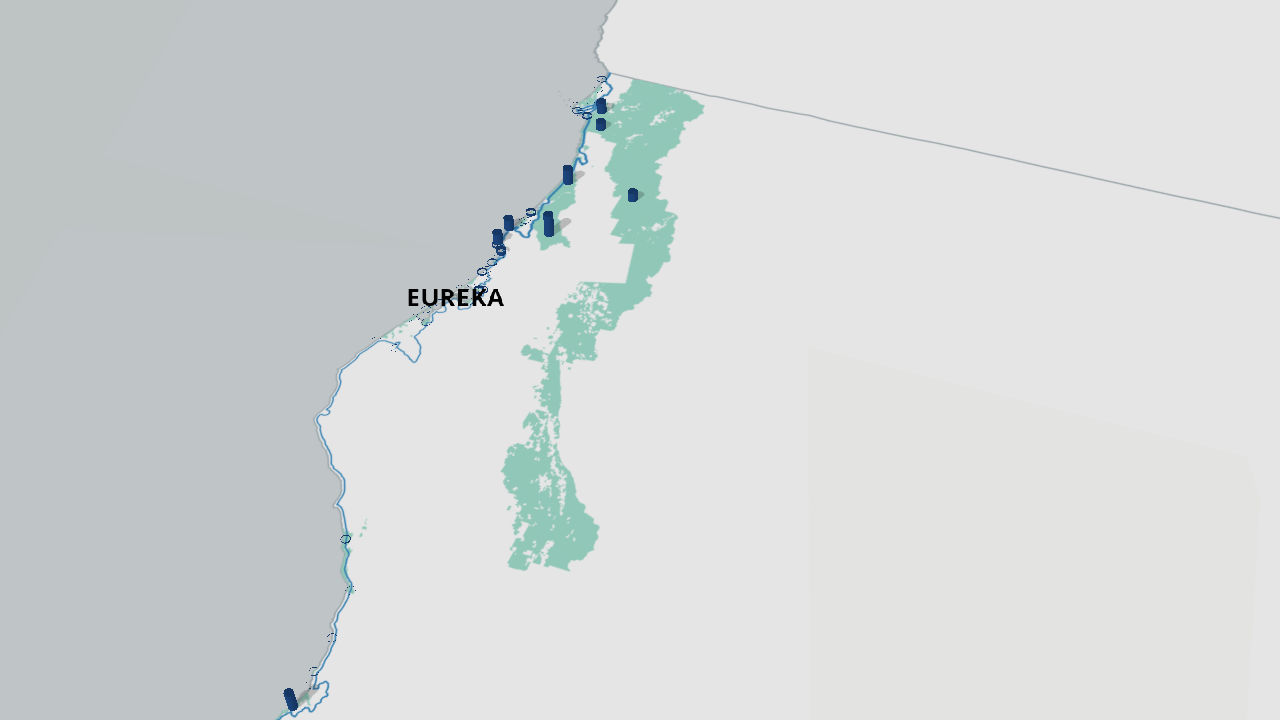

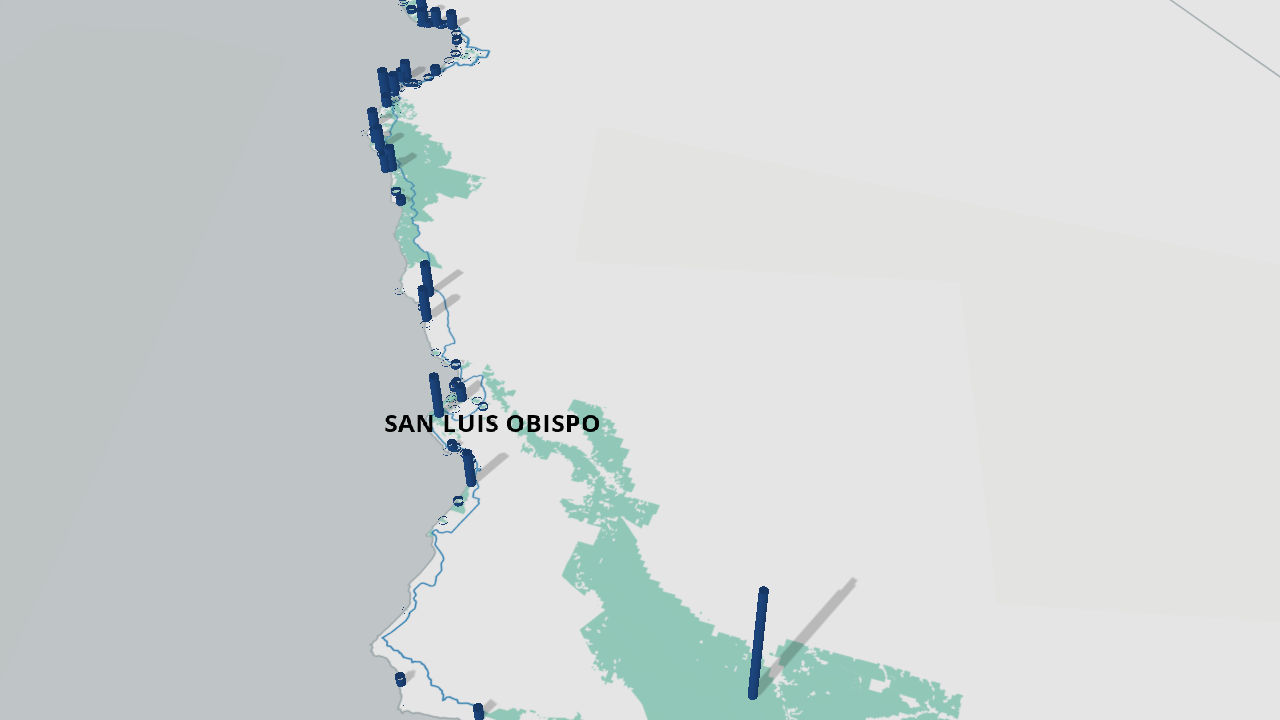

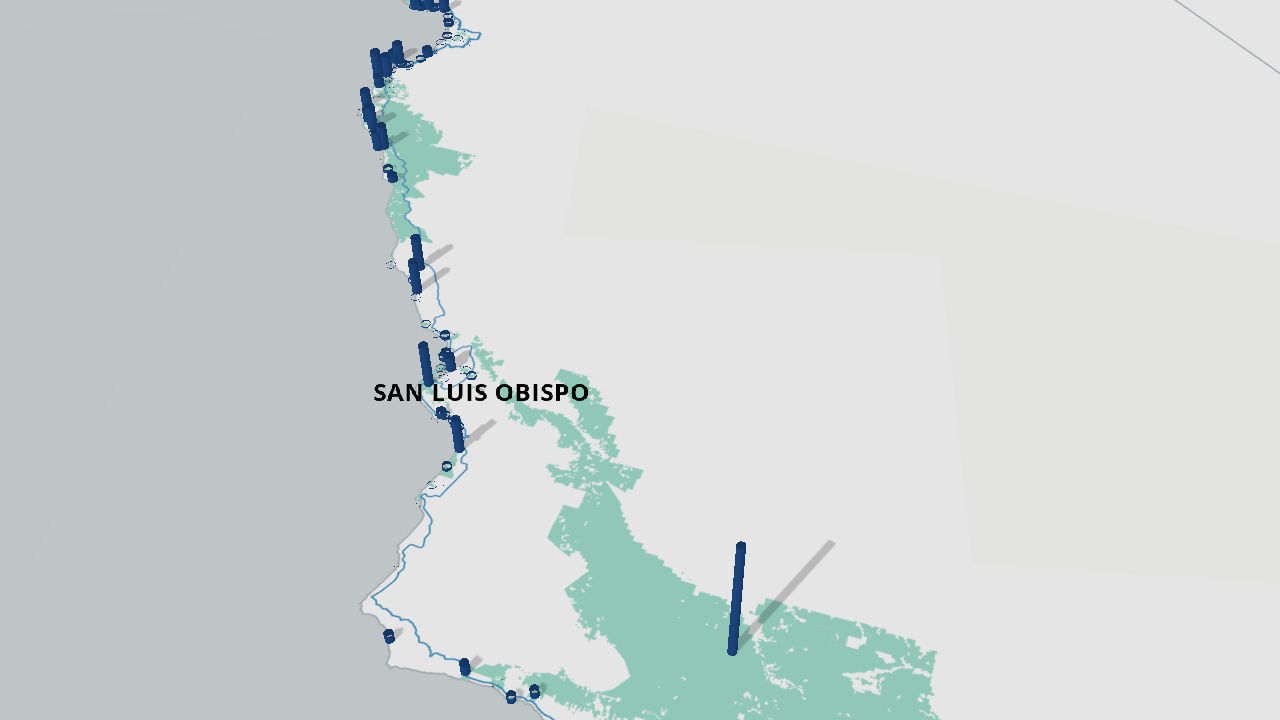

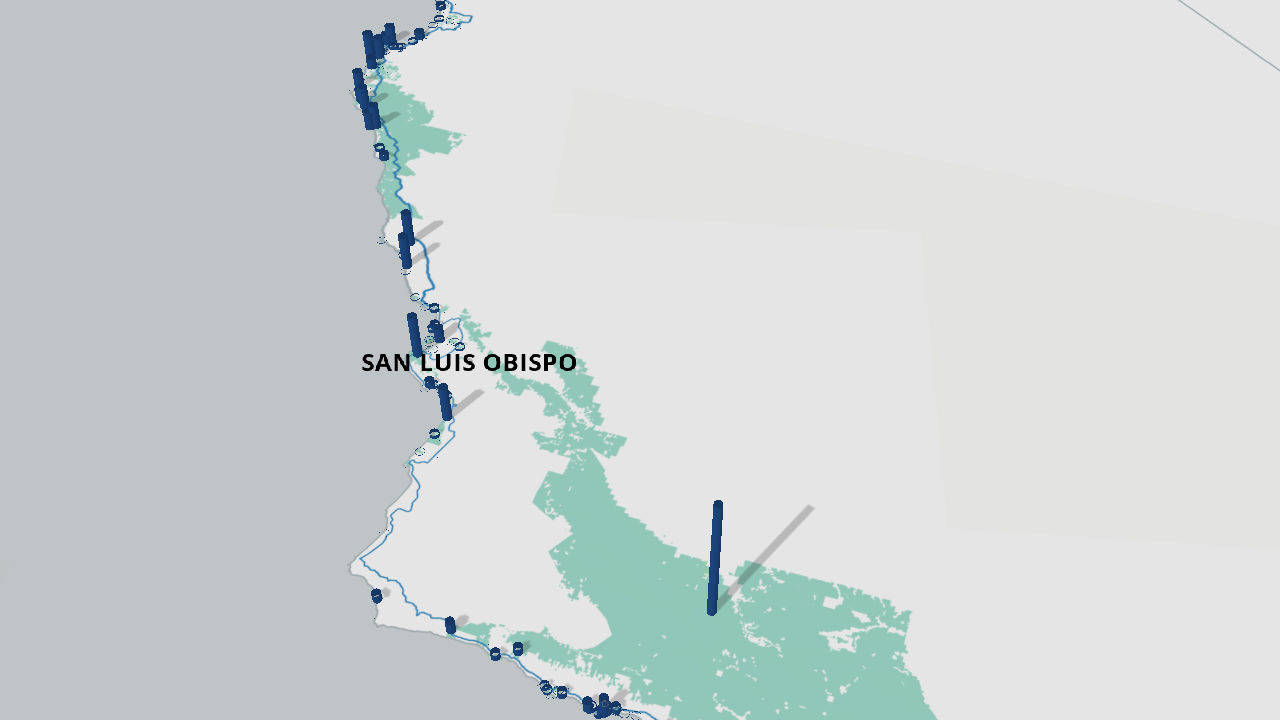

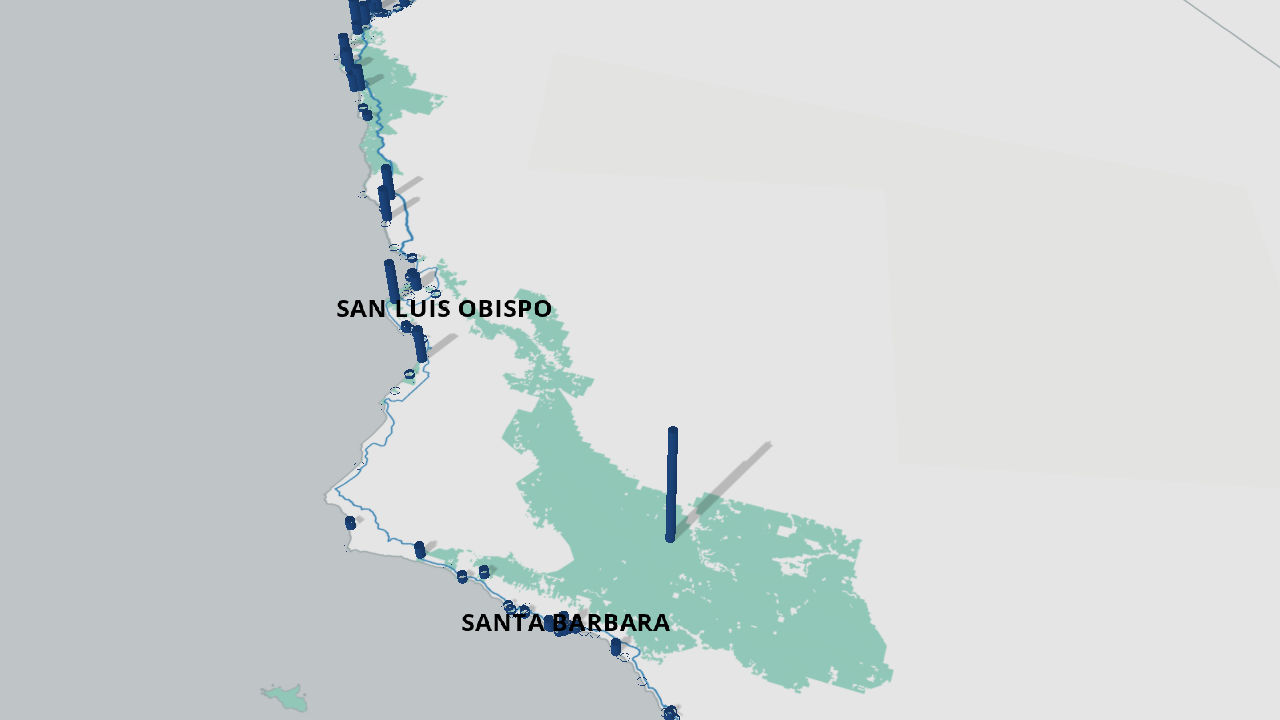

The California shoreline belongs to the people of California, as guaranteed by our state constitution. And the California Coastal Act states that "maximum access... and recreational opportunities shall be provided for all the people." There are 1,011 public beaches and parks within the state's coastal zone. On this map, we've used data from Instagram users at those beaches and parks to estimate relative visitation rates along the coast.

"I like the dramatic scene of waves crashing against rocky shores. I enjoy the rustic and ancient feeling that these beaches have, a reminder of a way of life a long time ago."

"I love to run. So the beach is the place I go for running. It's also a great place to meet new people."

"Since I was a kid, I've appreciated the sense of freedom playing on the beach, the ability to wander, and become immersed in the ocean ecosystem. I go to the beach with my family now, and we enjoy playing in the sand and looking into the tide pools."

"A lot of people think a perfect beach is one in commercials with two people in the middle of nowhere on lounge chairs. But that's just a vacation. The perfect beach is one you can go to every day and there are lots of people there and it's alive."

Californians Love the Coast

Beach lovers are park lovers

The coast is central to the lives of most Californians.

Nine out of ten people in our recent statewide survey told us the condition of the ocean and beaches is important to them personally, and three out of four visit the coast or a beach at least once a year, and many come much more often than that. The coast is a public resource and the California Coastal Act guarantees access for all of us. Preserving those connections for future generations is a crucial challenge for this generation of Californians.

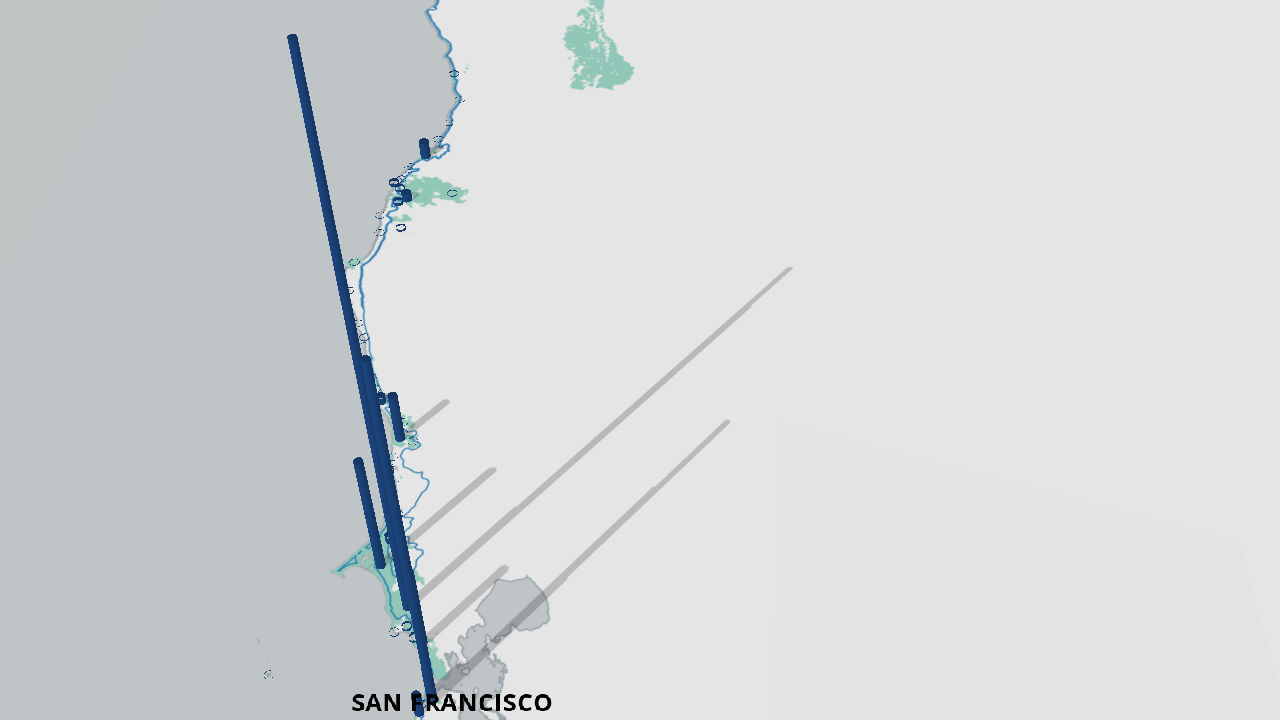

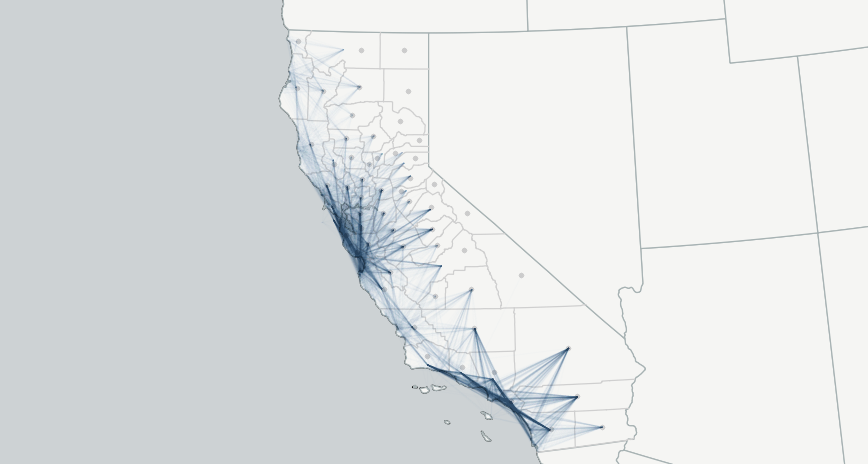

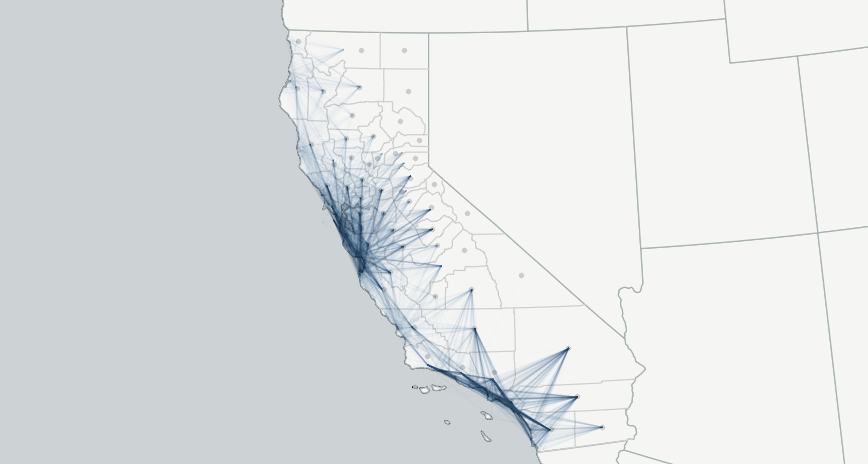

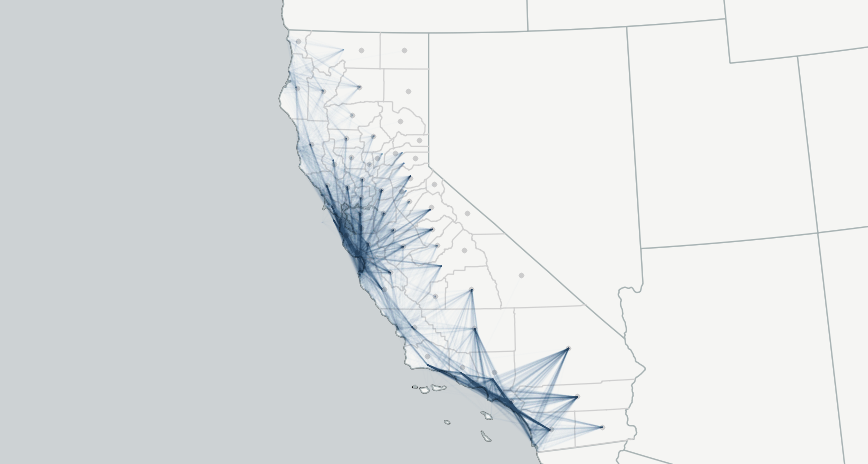

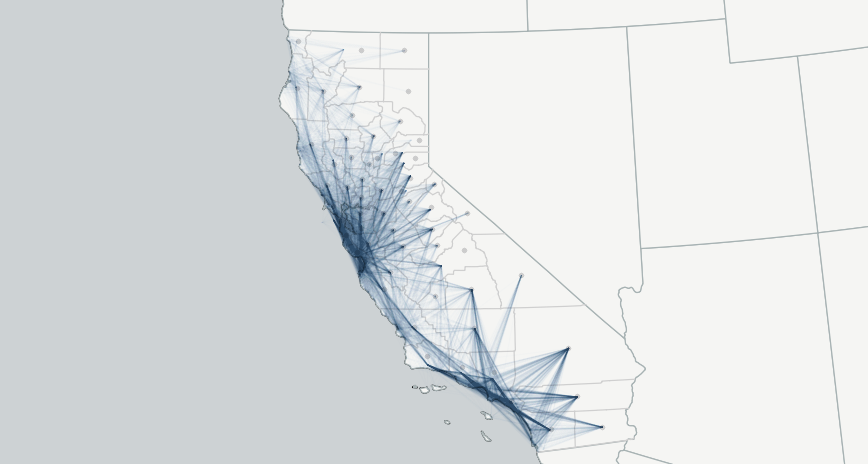

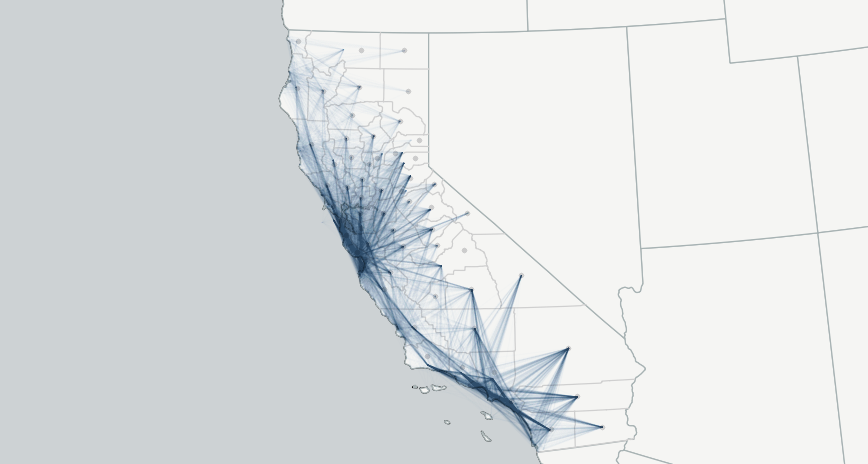

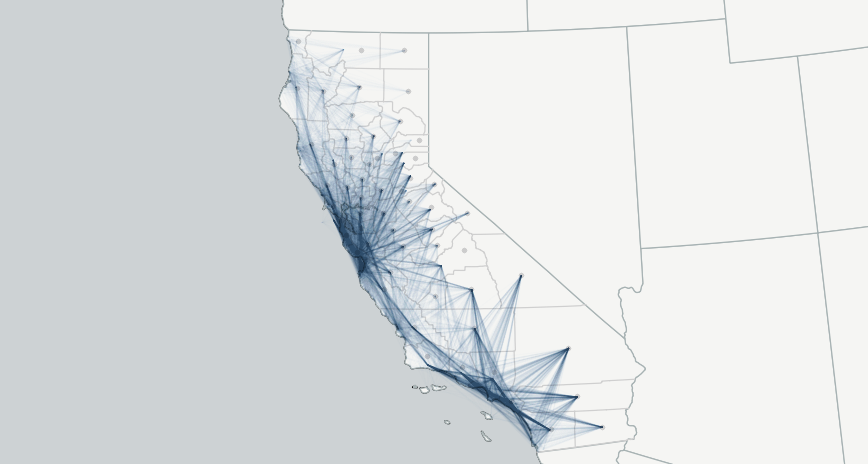

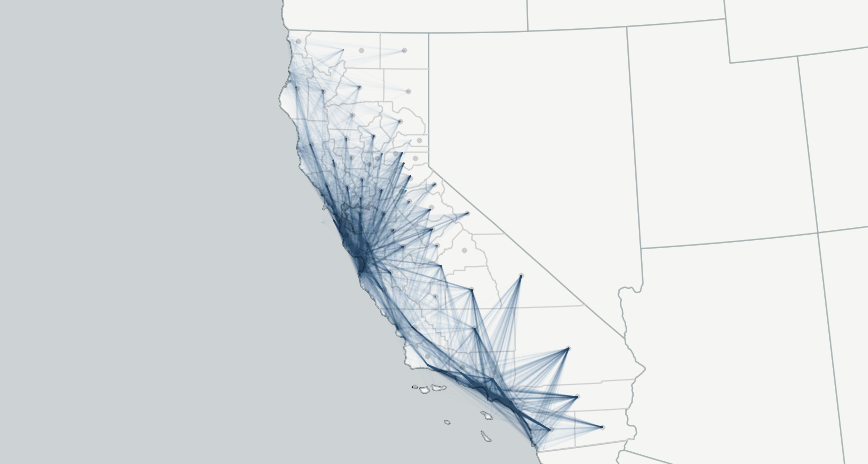

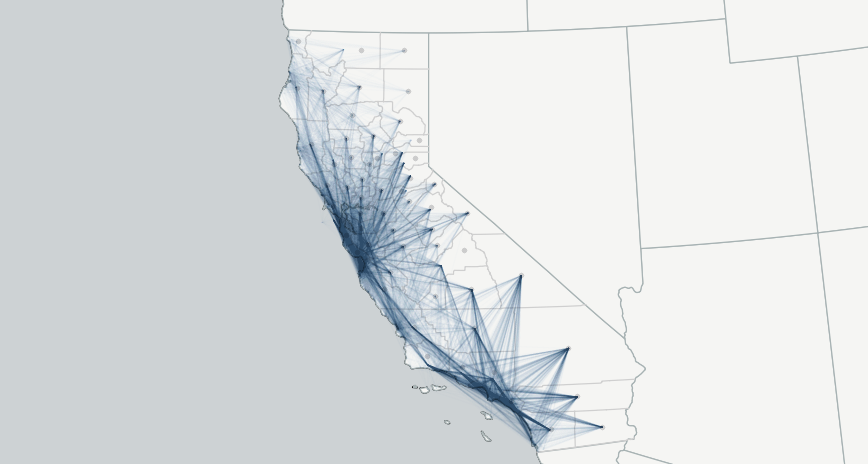

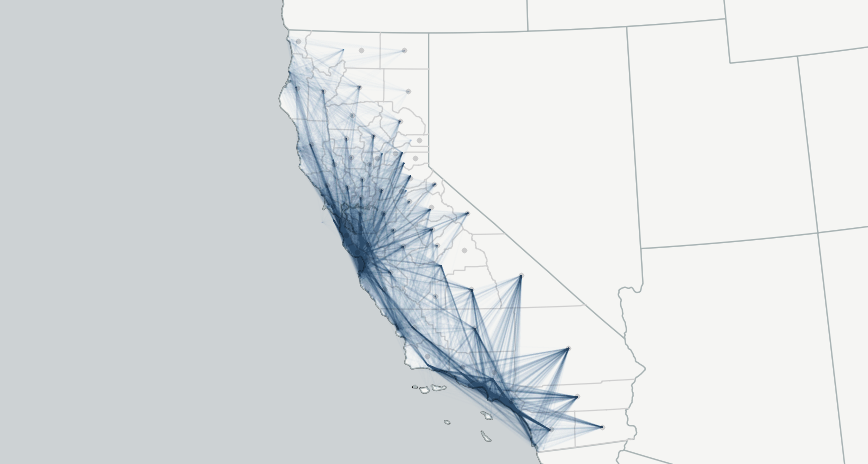

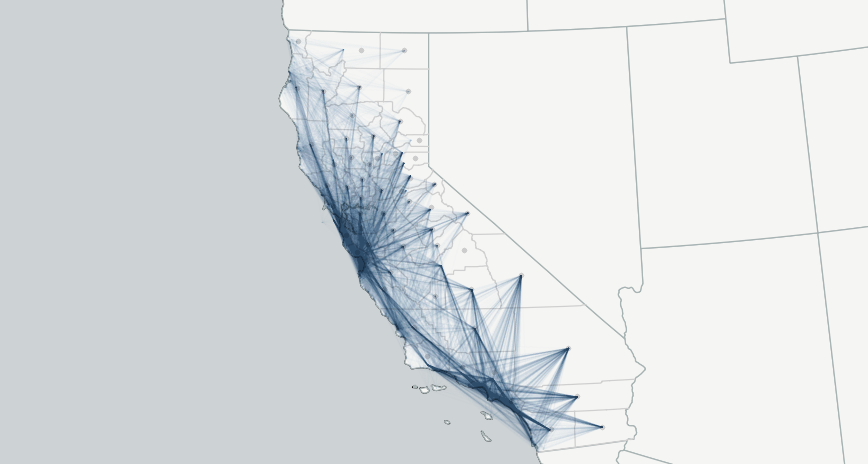

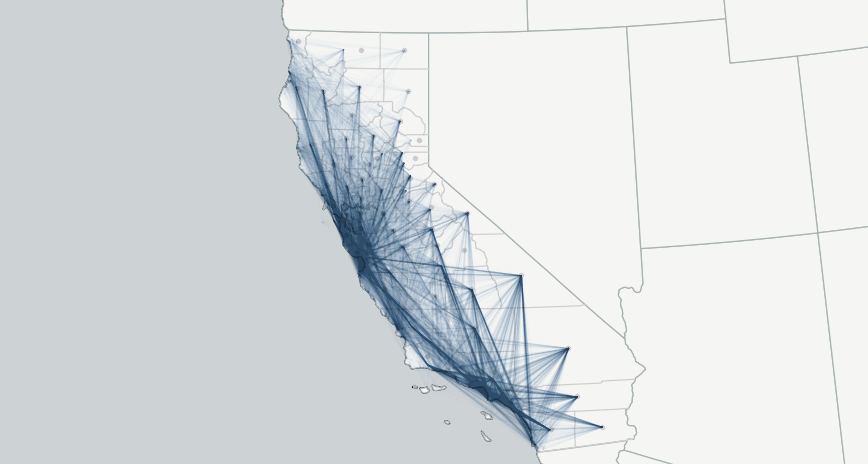

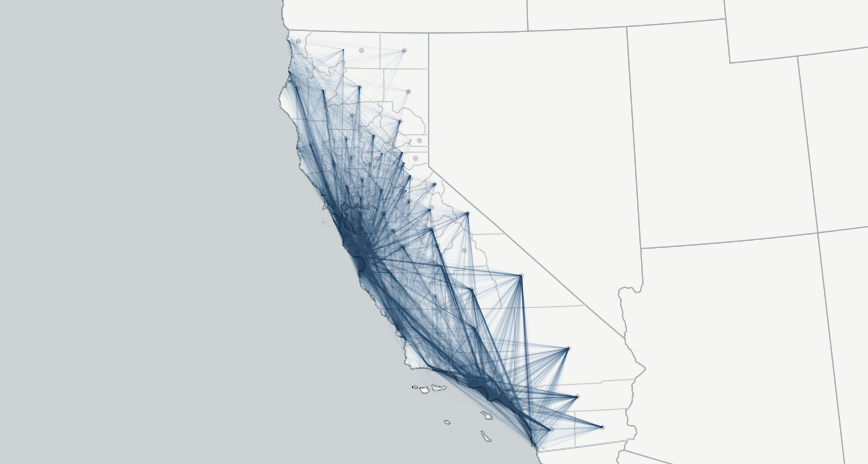

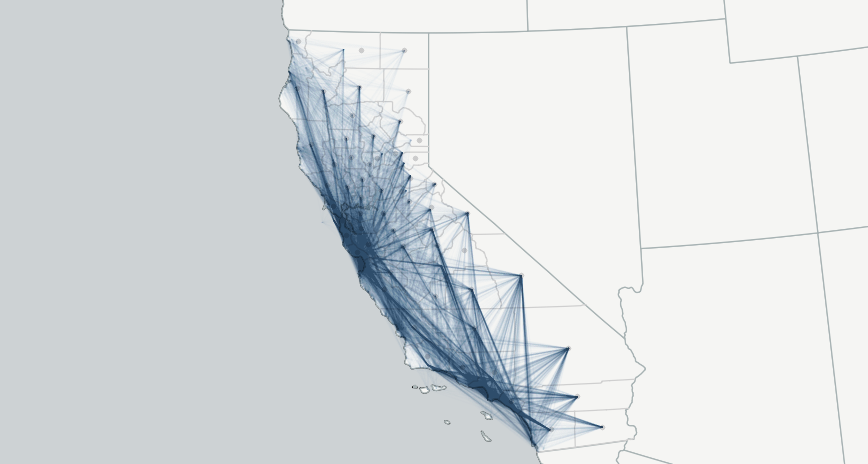

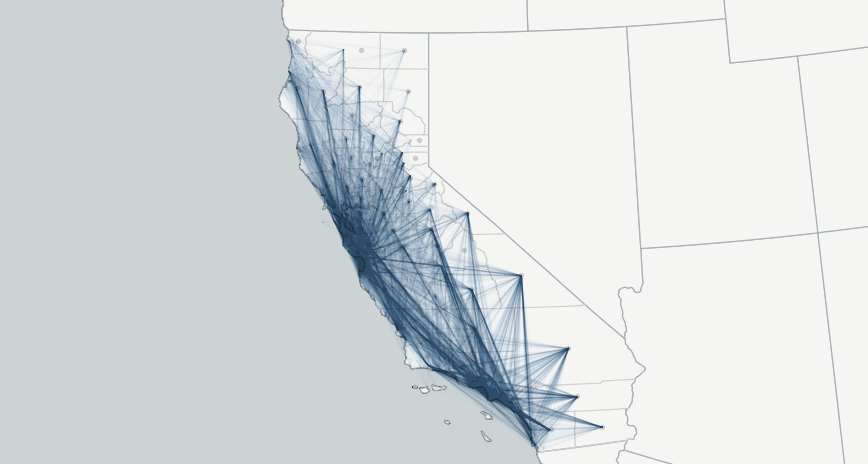

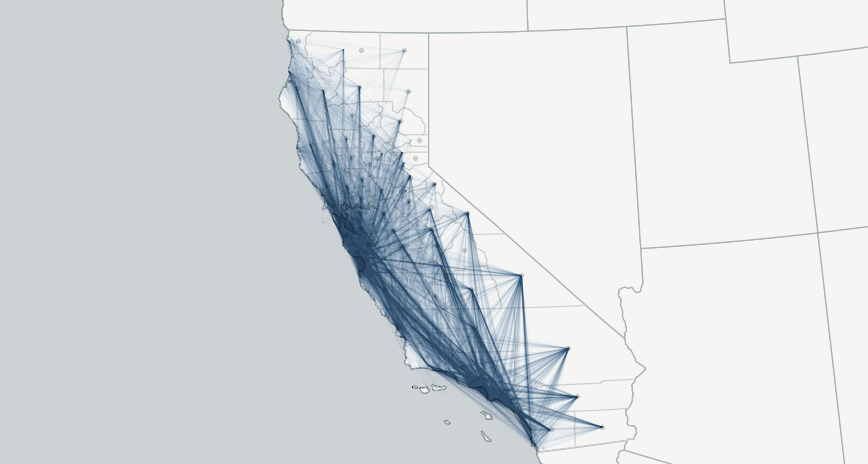

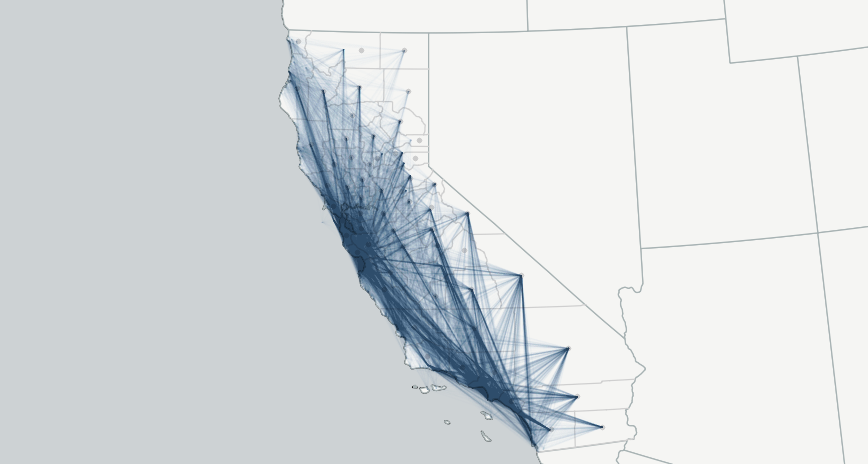

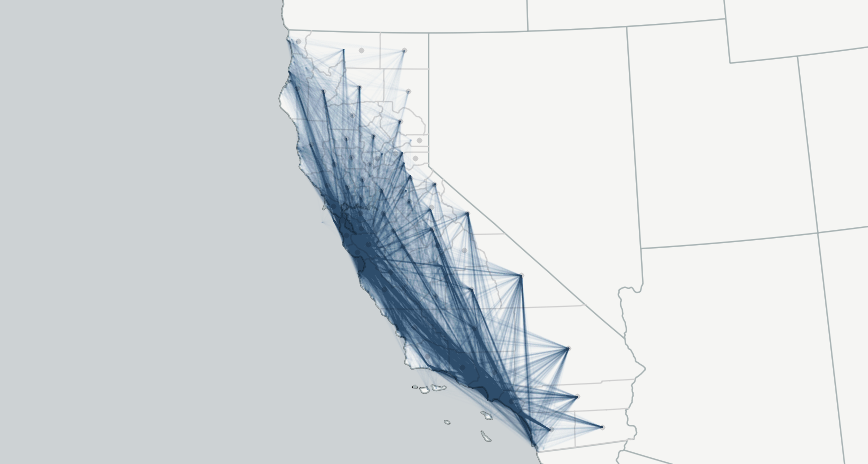

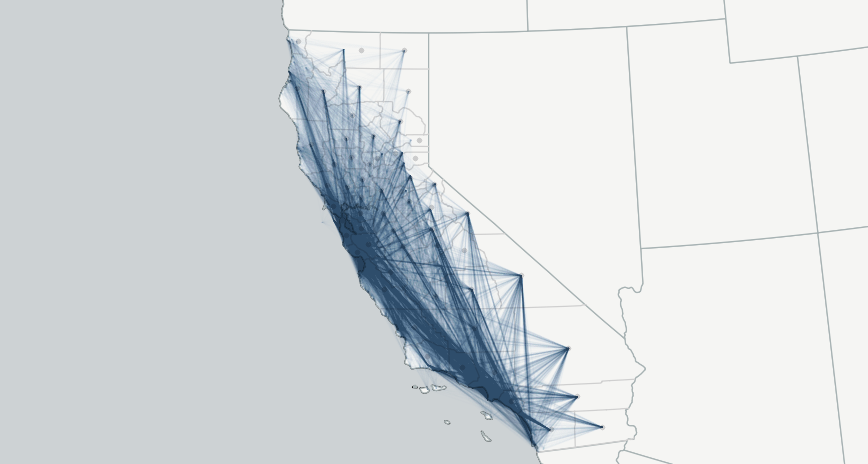

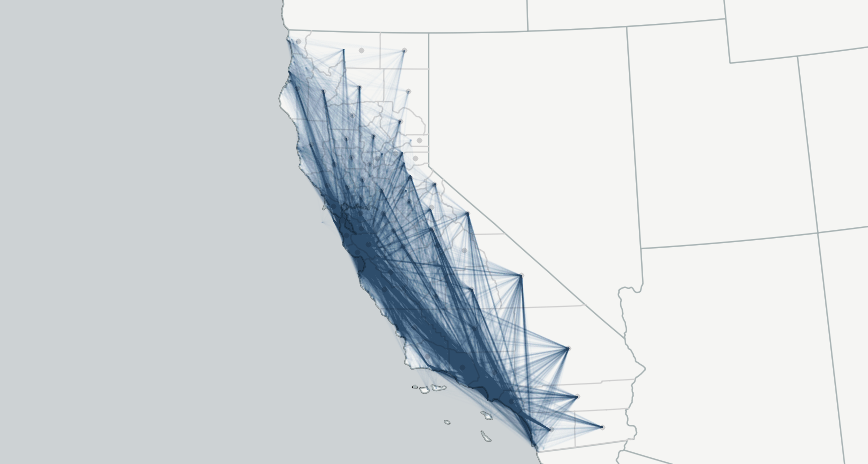

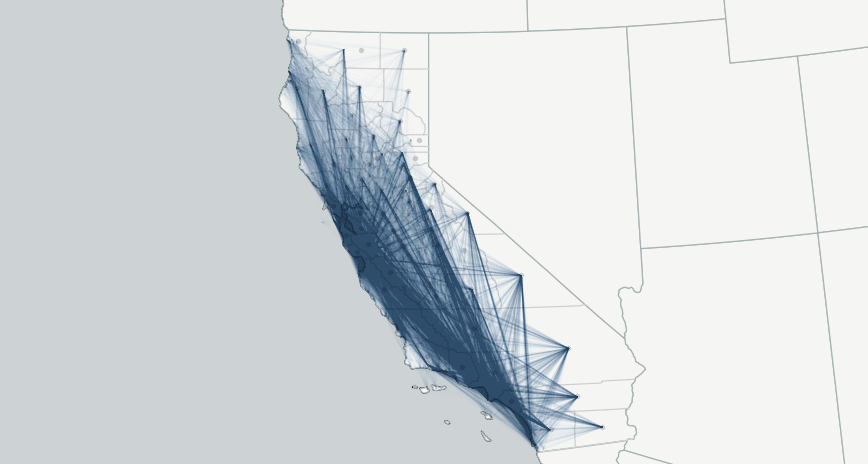

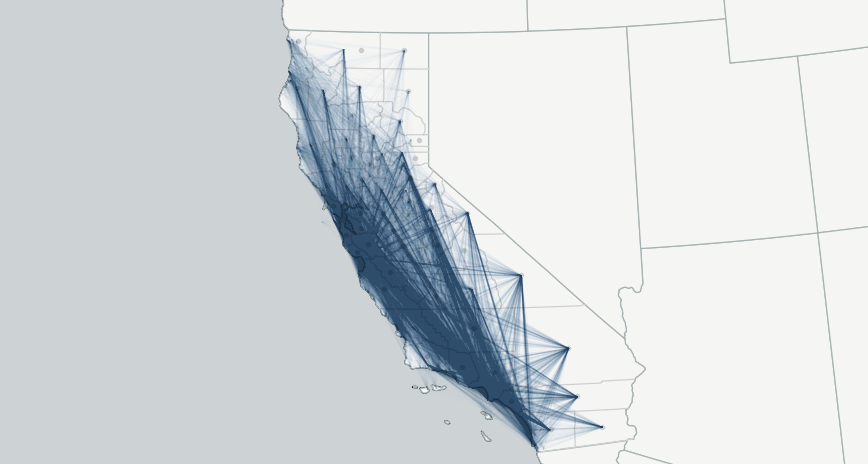

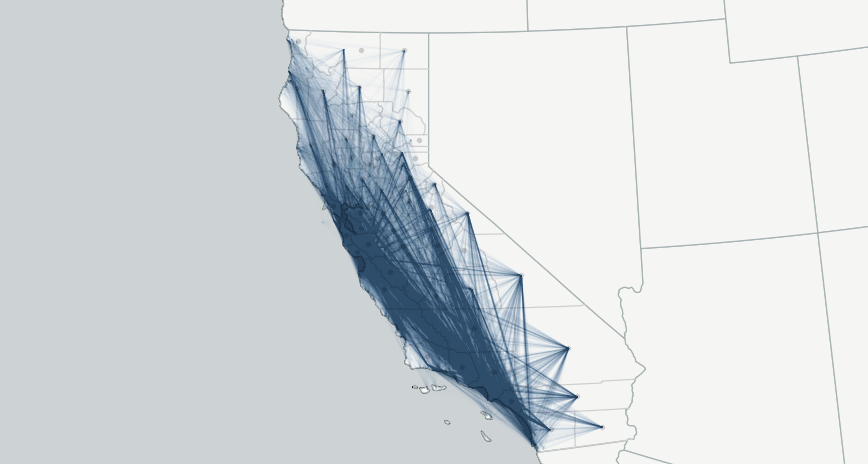

The map below shows Instagram users who post photos from both inland parks and coastal parks sharing their love of these important public spaces in every corner of California. Data courtesy of Stamen Design.

Californians Are Connected to the Coast

Beach lovers are park lovers. And park lovers are beach lovers. In this visualization the lines represent Instagram users in every California county who post photos from both inland parks and coastal parks and beaches, sharing their love of public spaces all over the state.

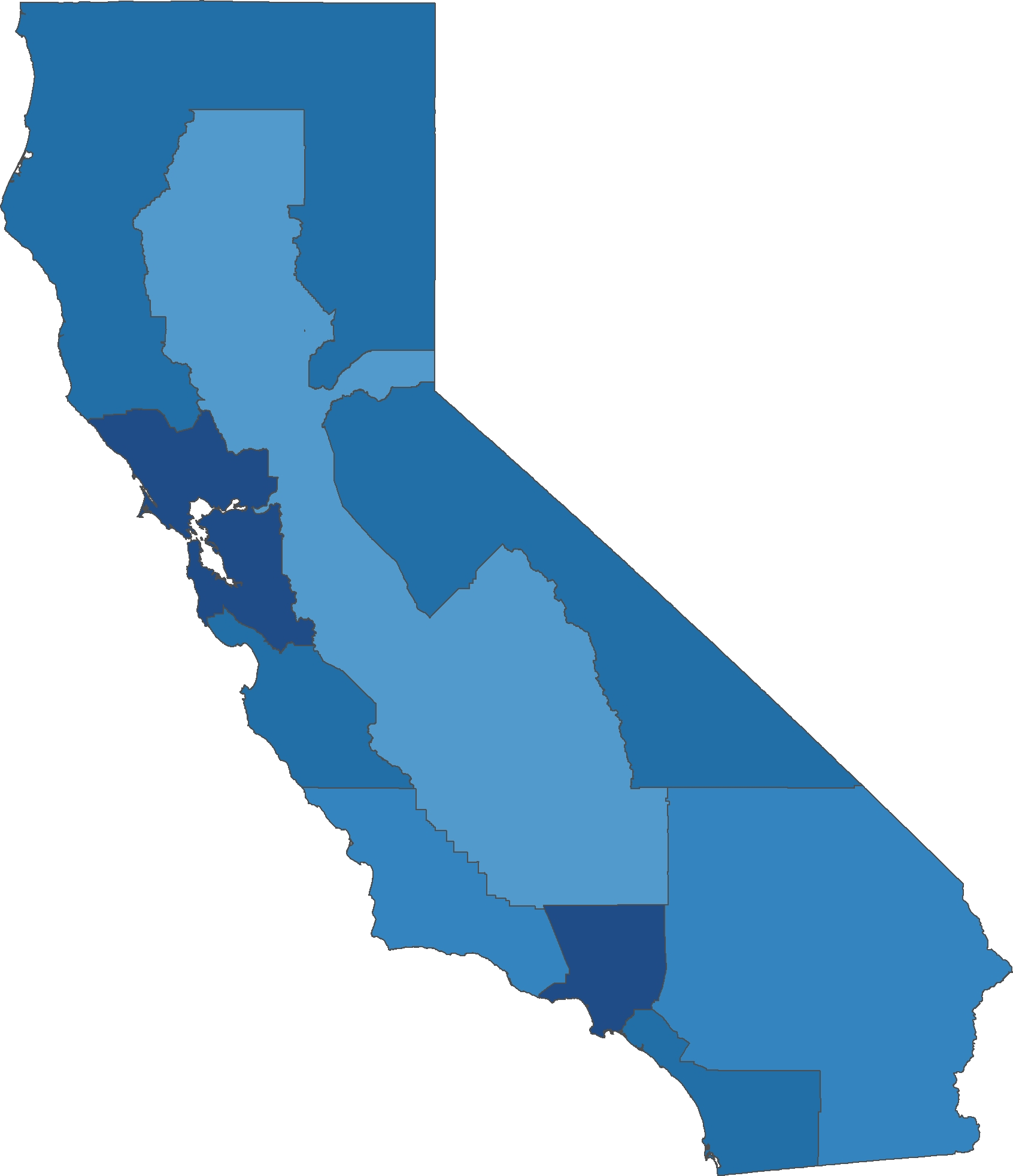

The percentage of people responding "very" or "somewhat" important.

82.5%

94.2%

82.5%

94.2%

How important is the coast to you?

Nine out of ten Californians say the coast is important to them personally. And the most important things at the beach for all Californians? According to our survey of beachgoers: clean sand, clean water, a place to relax and enjoy the scenery, and a place for kids to play.

The percentage of people who visit several times a year or more.

41.2%

73.8%

41.2%

73.8%

How often we visit the coast

Californians who live farther away from the coast don't visit as often. Distance and time are big factors, along with the cost of staying overnight near the beach.

Access to the Coast

Concerted efforts since the 1970s have preserved and opened up physical accessways

For decades, attempts by some property owners to block public access to the beach have attracted significant attention up and down the California coast.

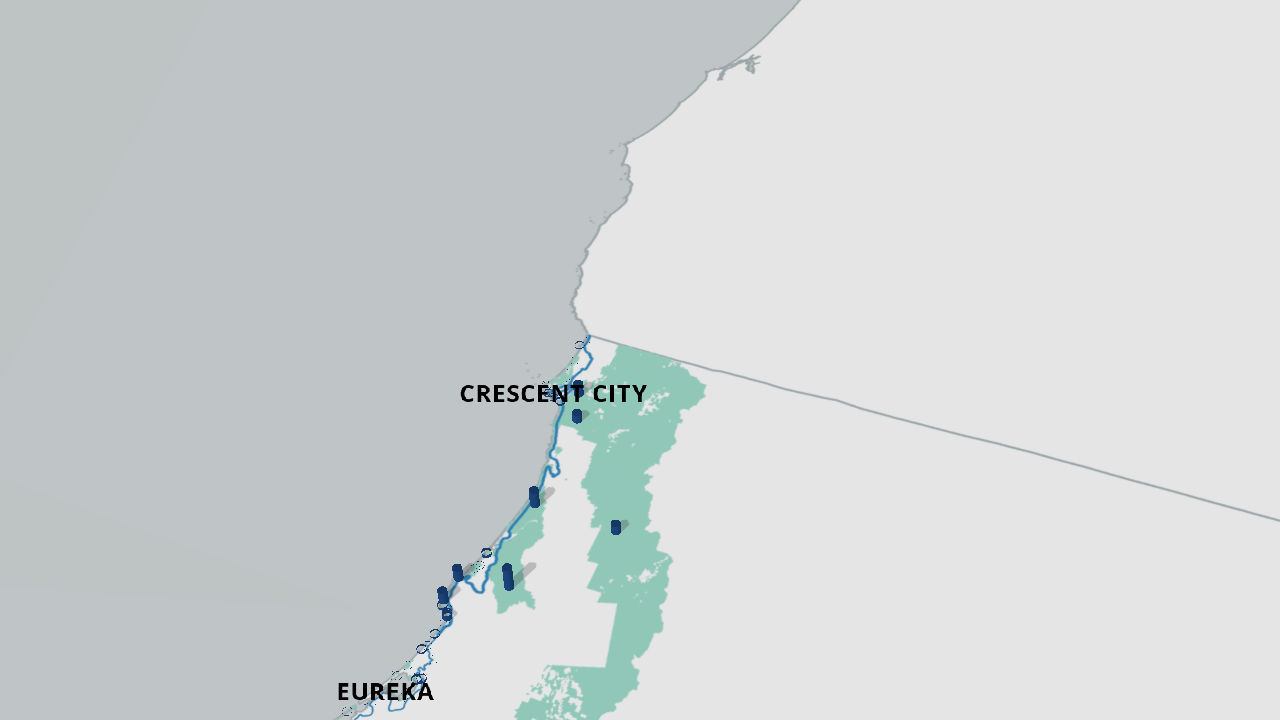

Since their creation in the 1970s, the California Coastal Commission and Coastal Conservancy have worked steadily through a backlog of physical barriers that impede access to the coast. Using negotiation, enforcement, and incentives for cooperation, they have opened up many direct accessways from public roads to the beach, as well as trails and open spaces that provide routes of travel and recreational areas along the coast.

Still, much work remains to be done to ensure California's beaches are readily accessible to the public all along the coast, from Mexico to the Oregon border.

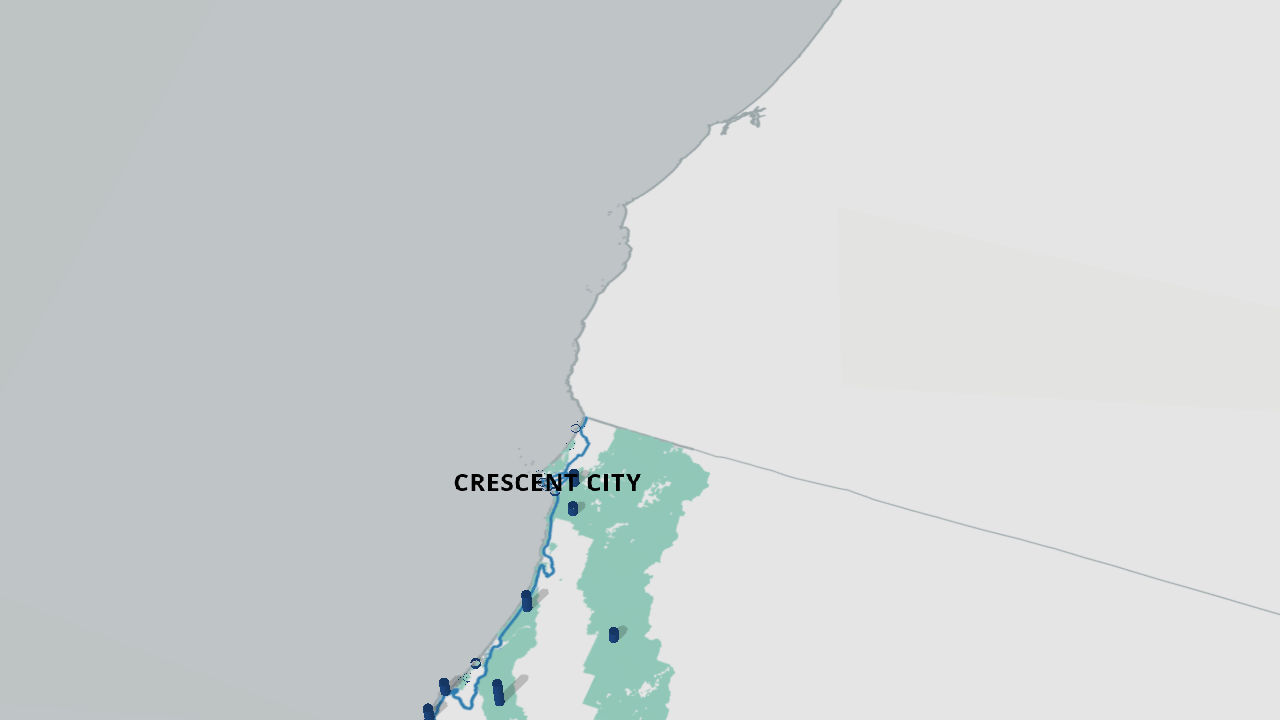

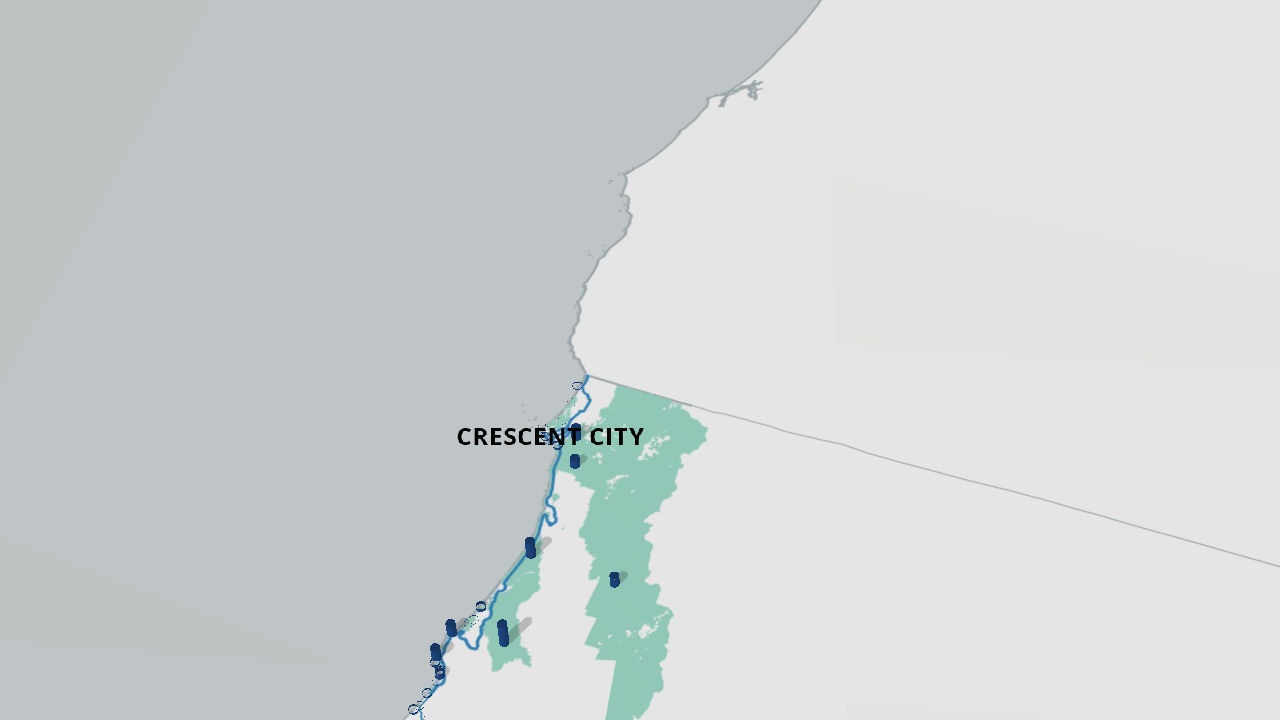

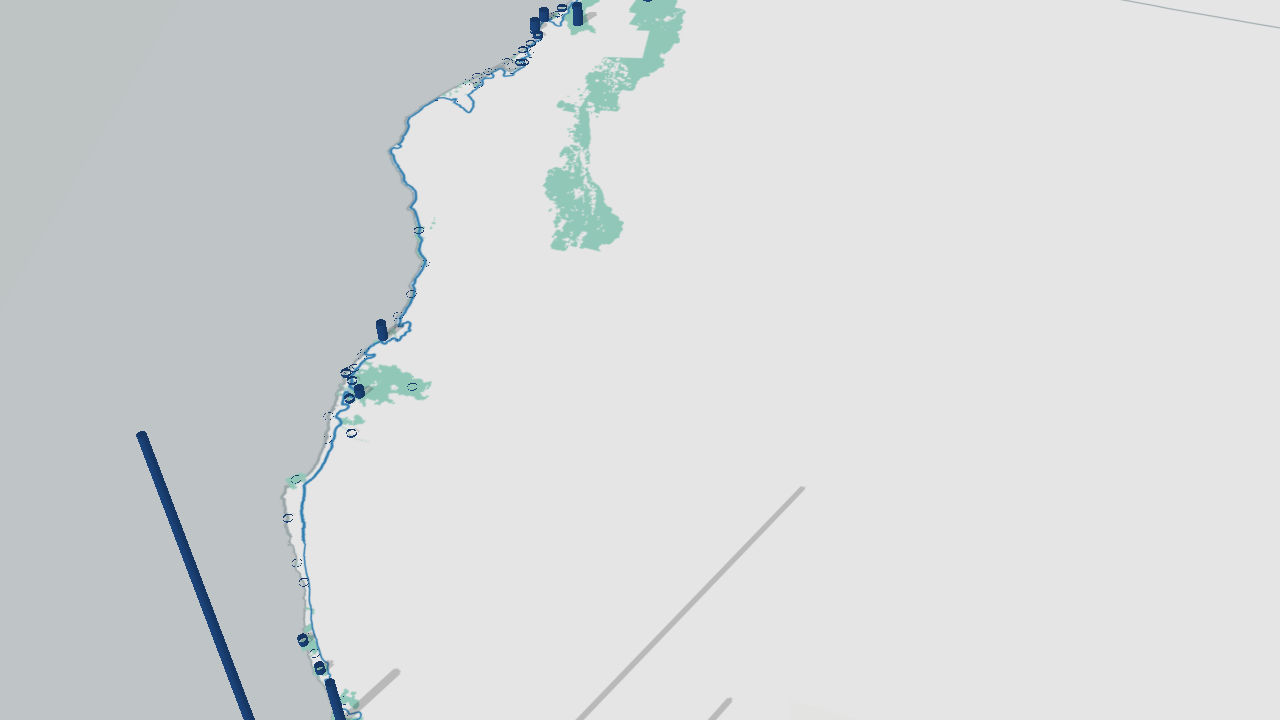

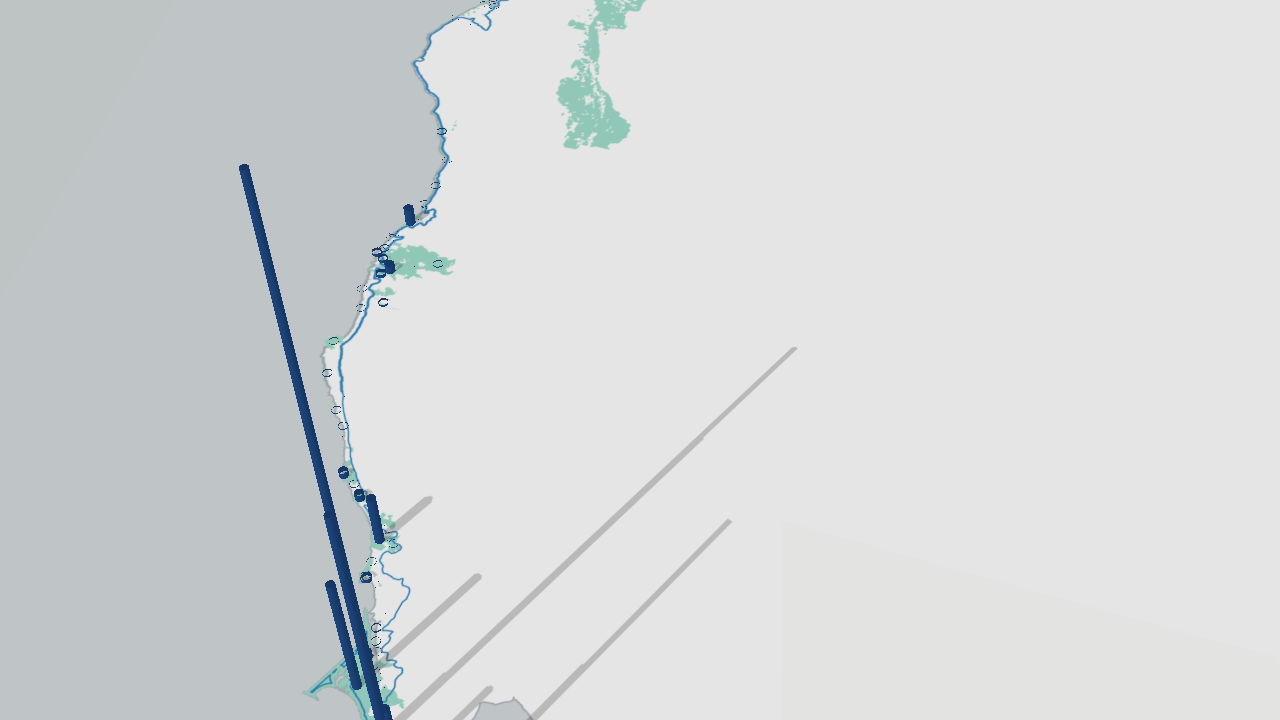

This graph shows accessways acquired by the Coastal Commission and opened to the public, along with accessways that have been acquired but are not yet open to the public as of September 2016.

Where can you access the coast?

This interactive map shows all of the access points currently open to the public along the California coast as of December 2016, according to the California Coastal Commission. You can use it to explore access points to stretches of the coast that you'd like to explore.

Today's Access Issues

Barriers to access beyond "the last hundred yards"

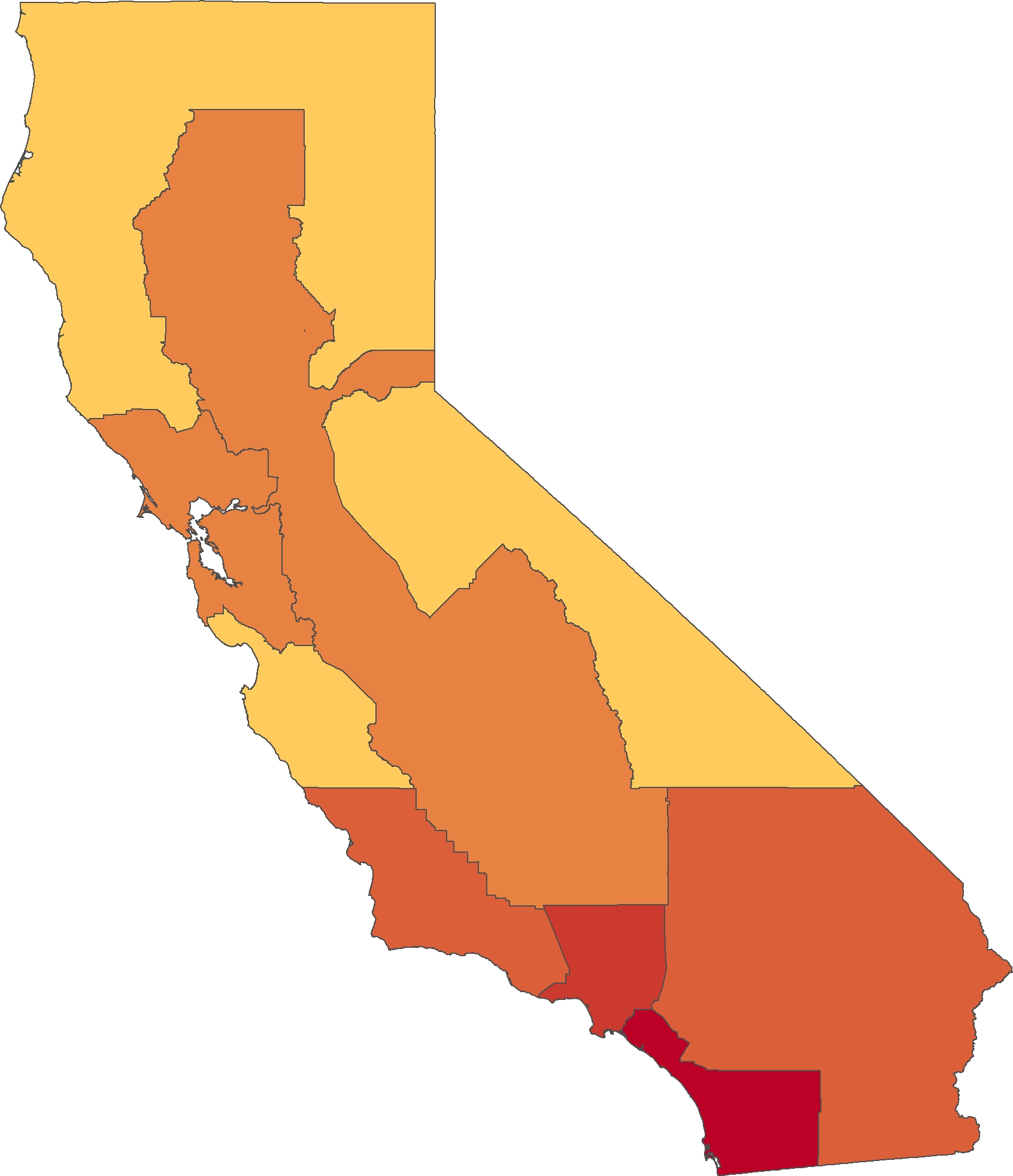

Despite the Coastal Act's directive that access and recreational opportunities should be maximized for all, and ongoing efforts to open direct access points along the coast, 62 percent of the people surveyed in our recent statewide poll said that access to the coast is still a problem.

Today, access to the beach doesn't just mean that the last hundred yards of a path to the sand and water are open. It means that all people have the opportunity to enjoy our coast and beaches.

Four obstacles to coastal access, ranked by California voters

Percent saying options for affordable parking are a problem

60%

90%

60%

90%

Barriers to access

Availability and cost of parking

Our recent surveys of beachgoers found that most visitors want to park close to the beach—within three blocks or even closer. And 78 percent of the people surveyed in our statewide poll said limited affordable options for parking along the coast are a problem. The average amount that people said they were willing to pay for parking was $8.25 per day. But we know that many visitors often pay more than that in many places that charge for parking along the coast. For a full discussion of "willingness to pay" methods, please download our full report below.

Percent saying limited public transportation is a problem

60%

90%

60%

90%

Barriers to access

Lack of public transportation options

Limited public transportation options for getting to the coast and beaches were cited as a problem by 68 percent of the people surveyed in our statewide poll and by more than 72 percent in Los Angeles and the San Francisco Bay Area. Some urban areas have good public transportation from some parts of the city to beaches but not from others. In Los Angeles, expansion of the Metro Expo line to within a few blocks of Santa Monica Beach at the beginning of summer 2016 created an upsurge in riders, demonstrating that there is pent up demand for public transportation to the coast, even if it doesn't go all the way to the beach.

Percent saying options for affordable overnight stays a problem

60%

90%

60%

90%

Barriers to access

Lack of affordable options to stay overnight

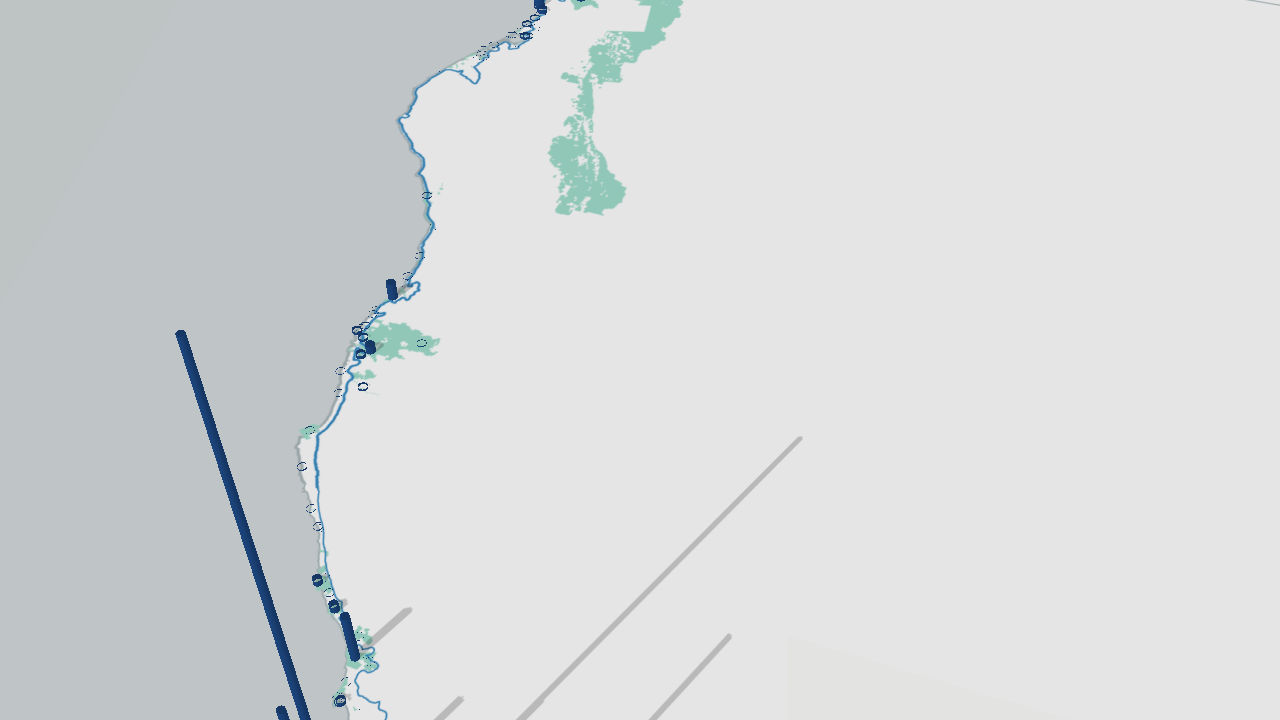

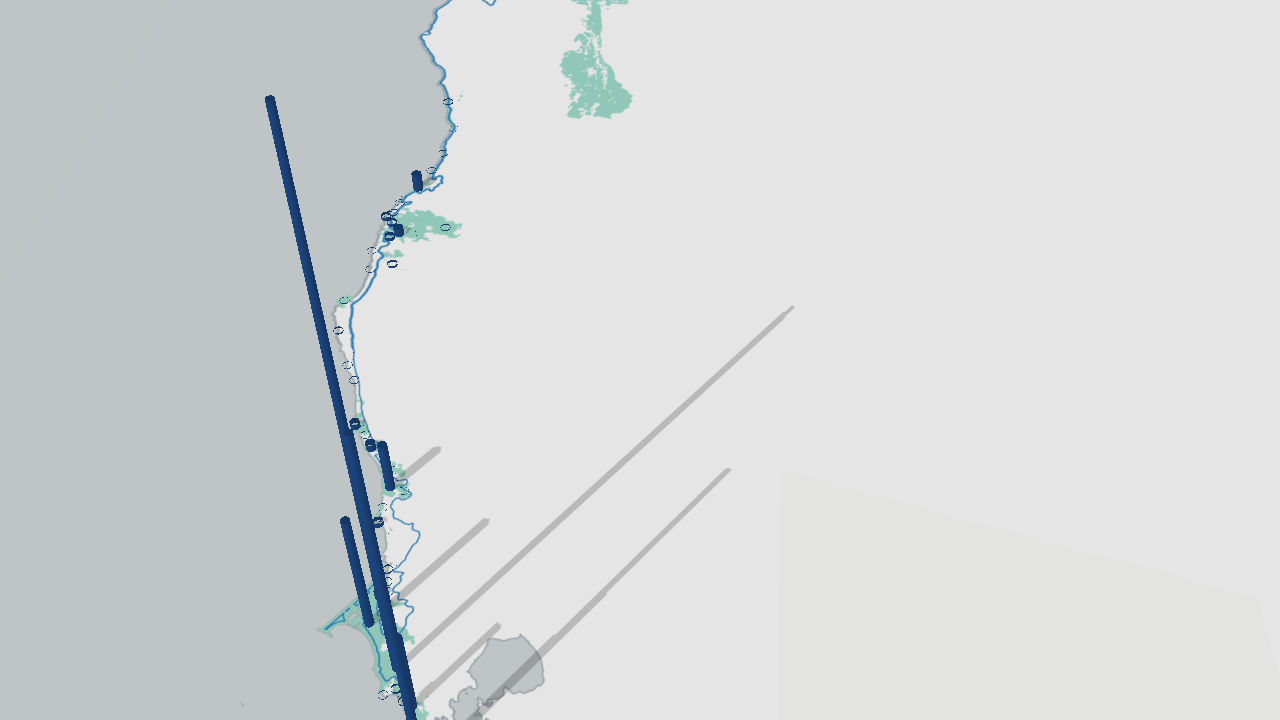

Staying overnight on the coast can be expensive, especially during the summer in the most popular places along the California coast. And it has gotten more and more expensive in recent years as affordable options have dwindled. Three out of four people in our recent statewide poll told us that the limited affordable options for staying on the coast are a problem. The average amount that people said they were willing to pay for overnight lodging on the coast was $117.65 per night. We know that finding a place to stay around that price point is often not easy. The map below shows "lower cost accommodations"—that charge a maximum of $112 per night—on the coast from a survey conducted by the California Coastal Conservancy in December, 2016.

Where can you find lower-cost overnight accommodations on the coast?

Explore the map below to find lower-cost overnight accommodations on the coast. Data courtesy of the California Coastal Conservancy and Sustinere. Please check rates with accommodation providers before making plans for a trip to the coast.

Alas, there are fewer and fewer lower-cost options for staying overnight on the coast

Since 1989, according to the California Coastal Commission, more than twice as many economy rate hotel rooms have been lost along the coast compared to all other hotel rooms at all other price points combined.

This graph shows the number of hotel rooms on the coast closed in each category.

Hotel rooms on the coast closed in each category since 1989

The cost of visiting the coast is at a tipping point for most Californians

We wanted to understand more about why Californians are so concerned about the cost of visiting the coast. So we estimated the value of trips to the coast based on our survey of beachgoers in Southern California in summer 2016 using a "travel cost model," a common economic method used to estimate the cost and value of trips based on people's actual behavior.

We found that the average total value of a day trip to the beach was $36.74 and that the average cost of traveling to the beach was $22.09, not including parking or other expenses, leaving a net value of $14.65 This finding gives us important information about why beachgoers are sensitive to the cost of parking. Even if parking were available for only $8.75 a day that would chip into the remaining net value of the average day trip, leaving only $5.90 net value. If parking cost $15 a day, the travel cost model would lead us to predict that the average visitor would decide to forego the trip because it would cost more than it is worth overall.

For overnight visitors, we found that the total value of the average trip to the coast was $605.05, with travel alone costing on average $194.41, leaving a net value of $410.64. Overnight visitors stay an average of four days on the coast, resulting in a net value of $102.66 per day. This finding gives us important information about why visitors are sensitive to the cost of overnight accommodations. If an overnight stay cost more than $102.66, the travel cost model would lead us to predict that the average visitor would not visit the coast.

Beachgoer Profiles

Despite their strong shared values, different coastal visitors have different needs and challenges

We need to understand that while coastal access is important and guaranteed for all by the Coastal Act, our beaches are democratic spaces, and while people want many of the same things when they come to the beach, not everyone has the same needs and faces the same challenges to access the beach. Through our statewide poll and beach surveys we found that identifying some of the various factors that affect different kinds of beachgoers can help us think through strategies to address these needs and challenges.

Young People

Young people, 18 to 24 years old, are more likely to come to the beach alone to swim or wade. Public transportation is more important to them. And they are concerned about cost, particularly the cost of overnight accommodations at the coast.

Families

Families with adults 35 to 44 years old tend to come in larger groups. They want a place for their children to play. And they are more likely to stay in a hotel if they stay overnight on the coast. They are more concerned about the availability of affordable parking adjacent to the beach and the cost of overnight accommodations.

Latinos

Latino beachgoers are more likely to be millennials, families with children, seeking a place for their children to play. They come in larger groups. Amenities such as parking, restrooms, and trash cans are more important to them. And they like to see lifeguards on duty. They're concerned about the cost of parking and overnight accommodations and the lack of public transportation options for getting to the beach.

Older Beachgoers

Visitors over 75 years old are more likely to come to the beach alone or with one other person. They come to walk on the beach. They want parking nearby and are concerned about the lack of public transportation. Cost is a concern for them. They spend less time each day on the beach, and visit less often, but their overnight stays are longer.

Beach visitors who travel longer distances

Beach visitors who travel longer distances to the coast tend to be most concerned about cost, and particularly the cost of overnight accommodations. They tend to stay overnight, and often for several nights when they visit the coast.

Working on New Ways to Open Up Coastal Access

Three examples among many

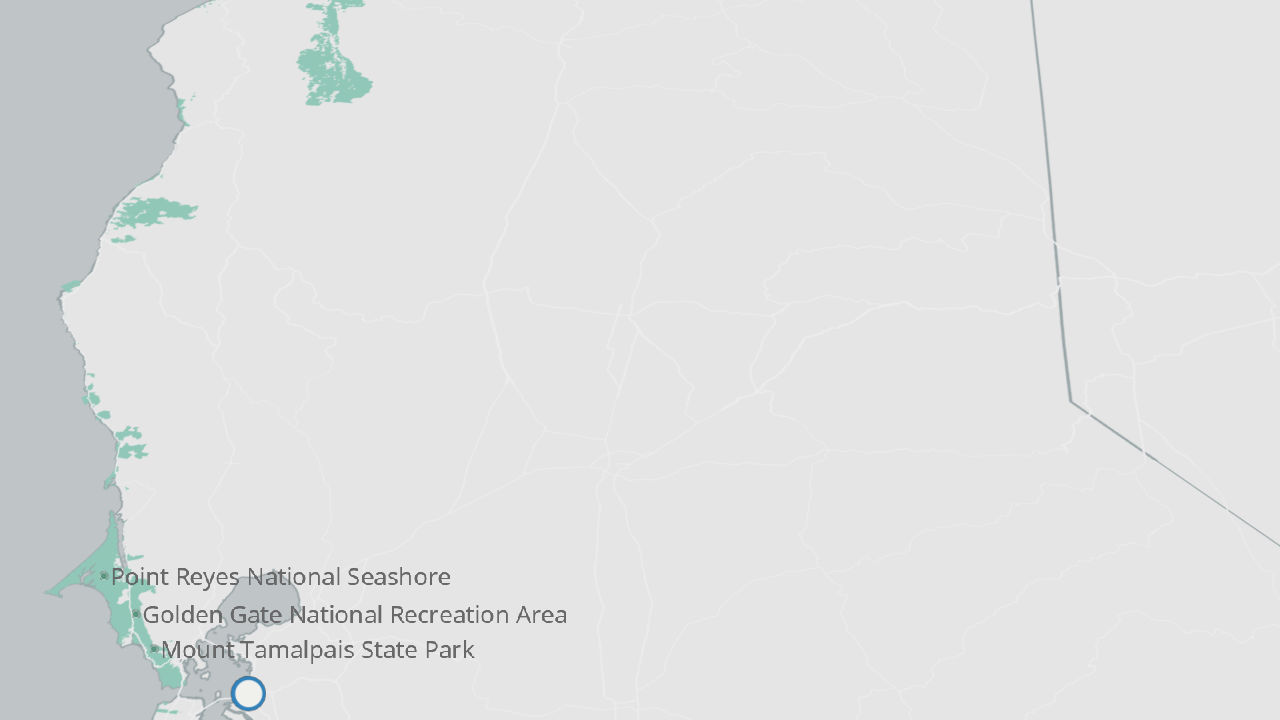

There are many organizations around the state, in coastal and inland communities, advocating for solutions to the complicated challenges of providing coastal access for all today. As Mira Manickam-Shirley, the co-founder and executive director of Brown Girl Surf in Oakland, says, to meet today's coastal access challenges, "we have to go beyond technical solutions to thinking about community and everyday culture." Here are three examples of organizations doing that work.

Brown Girl Surf (Oakland)

Brown Girl Surf has connected 131 girls from Oakland, San Francisco, and the South Bay to the coast and ocean through surfing in the last two years. Many of them had never visited the coast, despite living nearby. The program shows girls "that the ocean is not someone else's place," says Mira Manickam-Shirley. "It's theirs. And they have a way to access it, to see themselves reflected there, and enjoy it."

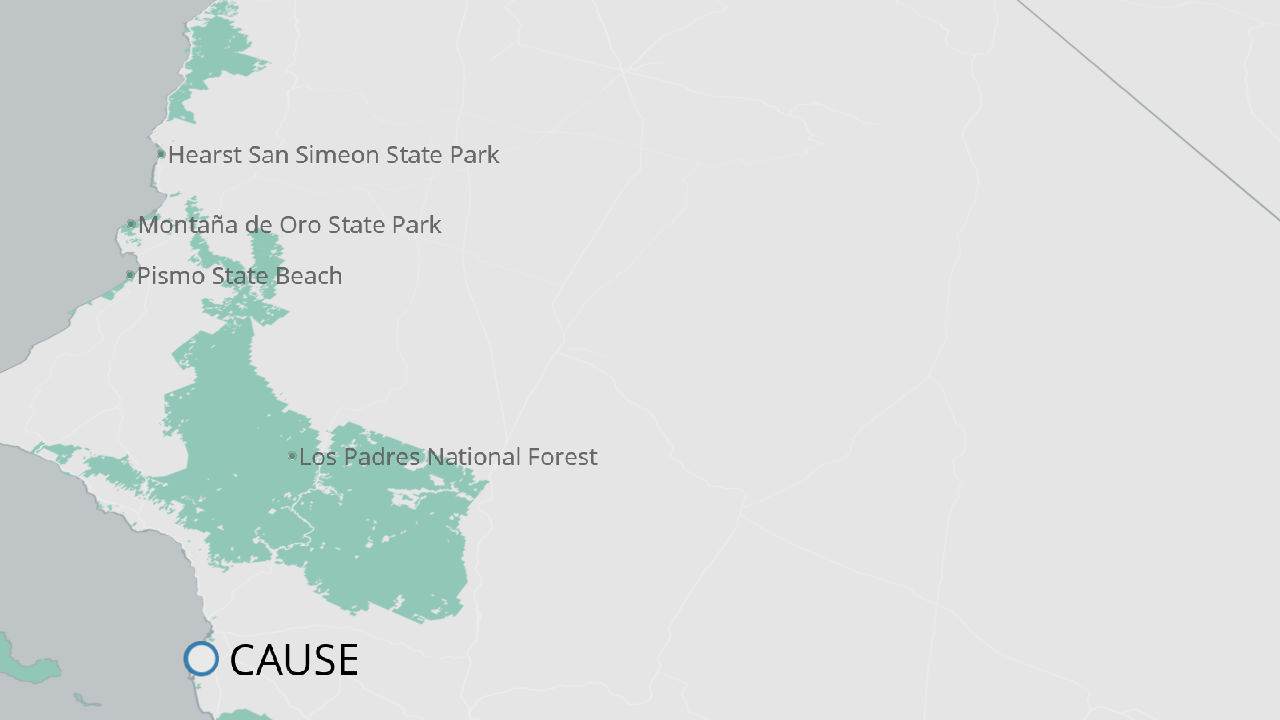

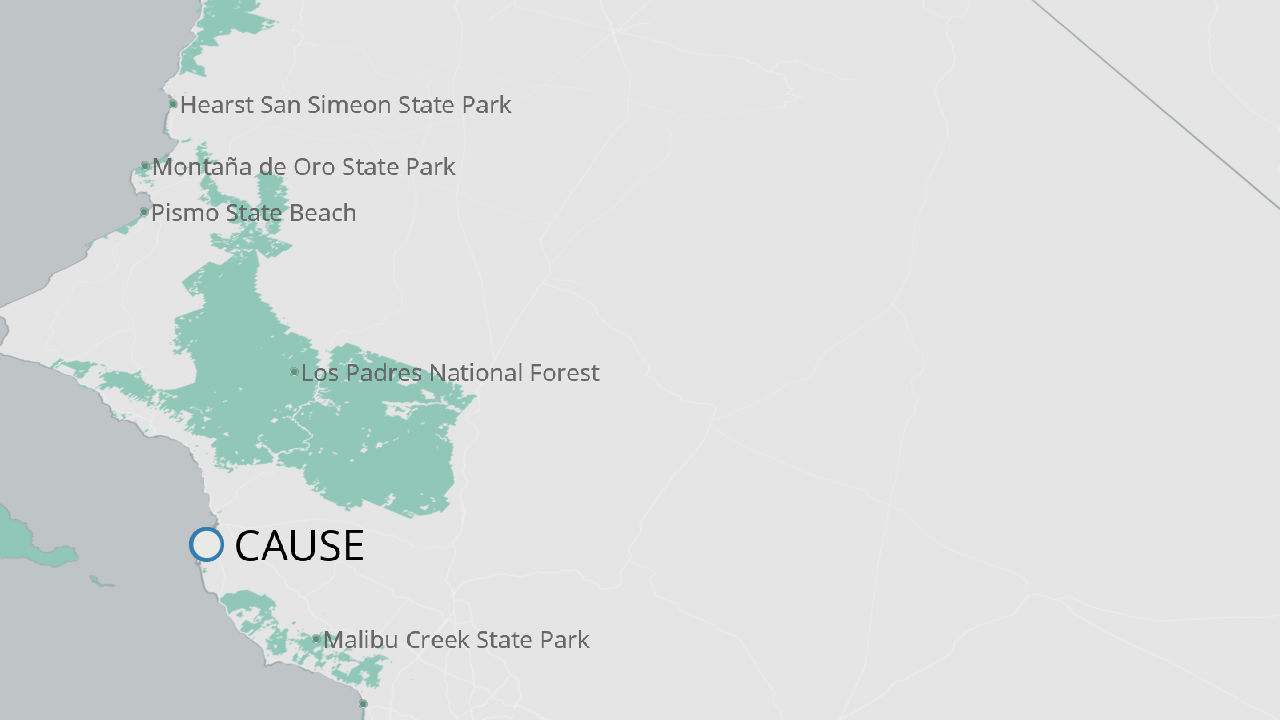

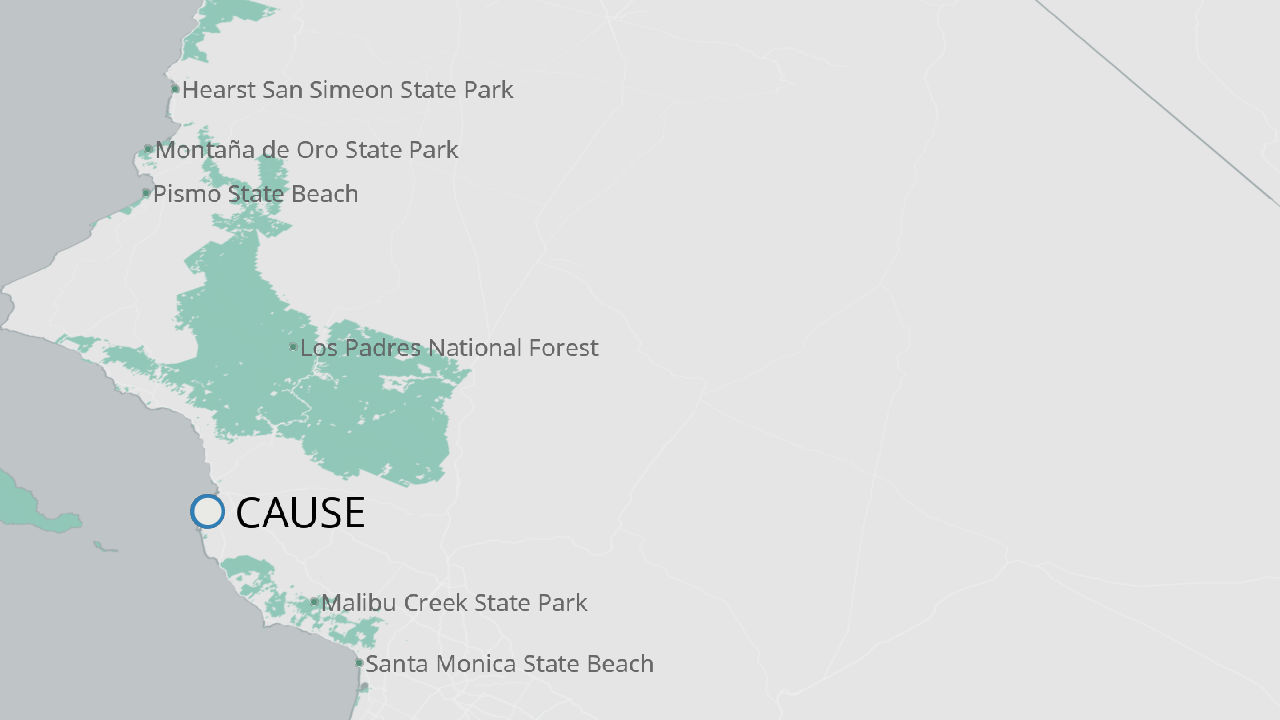

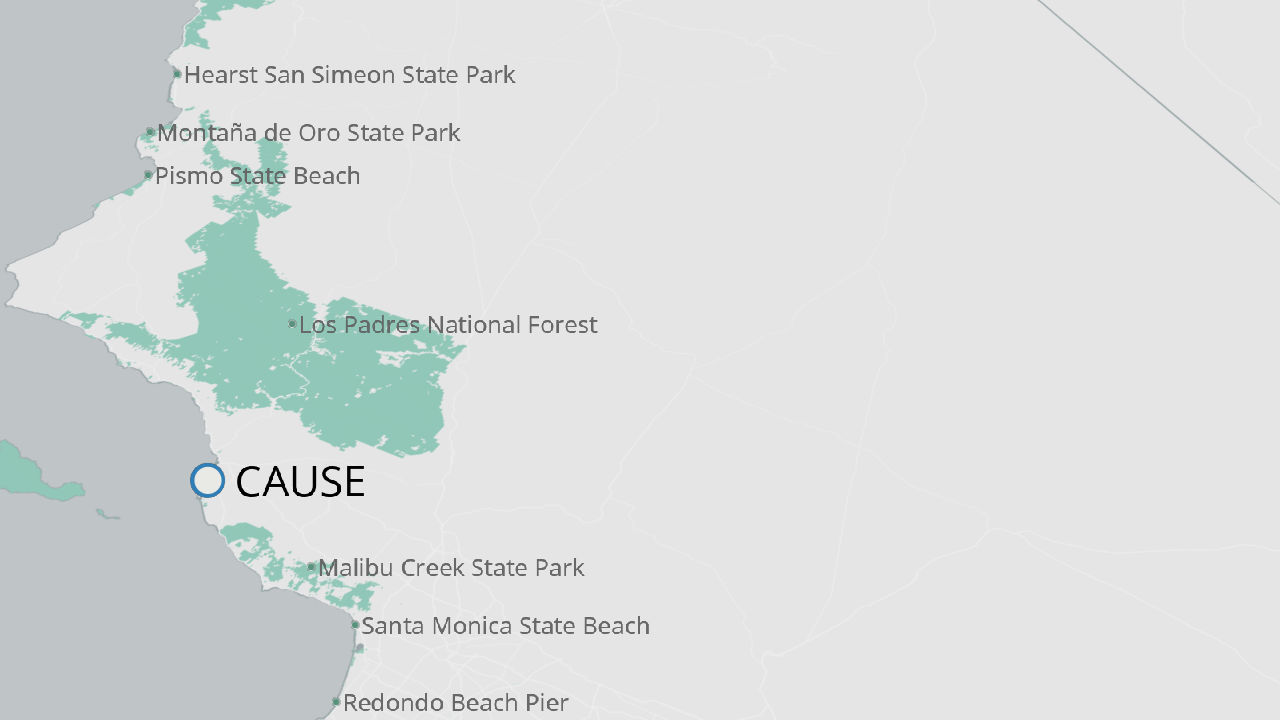

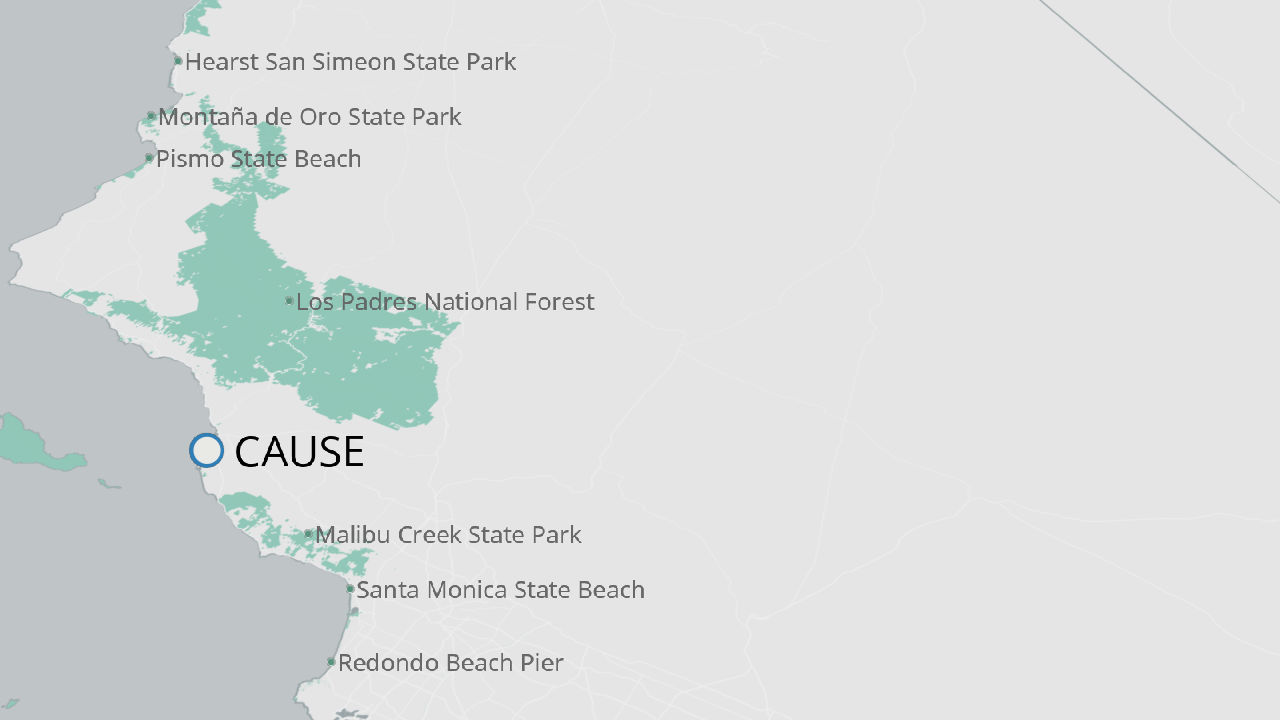

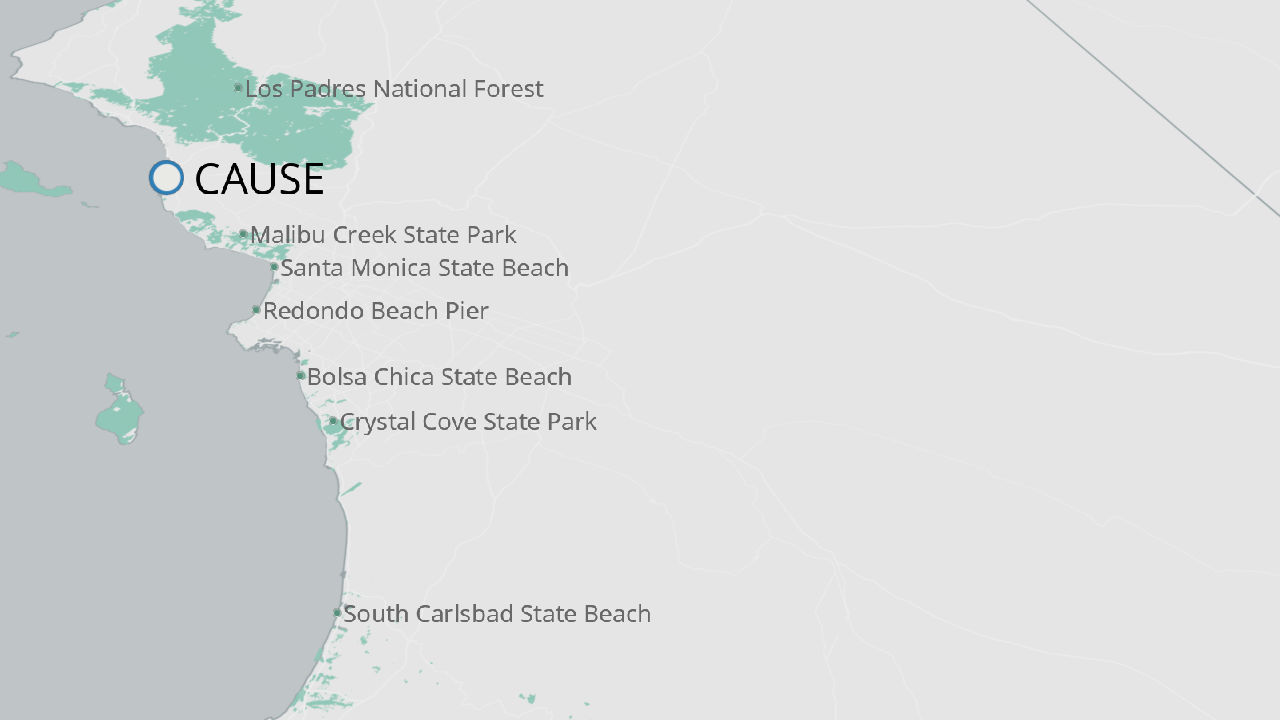

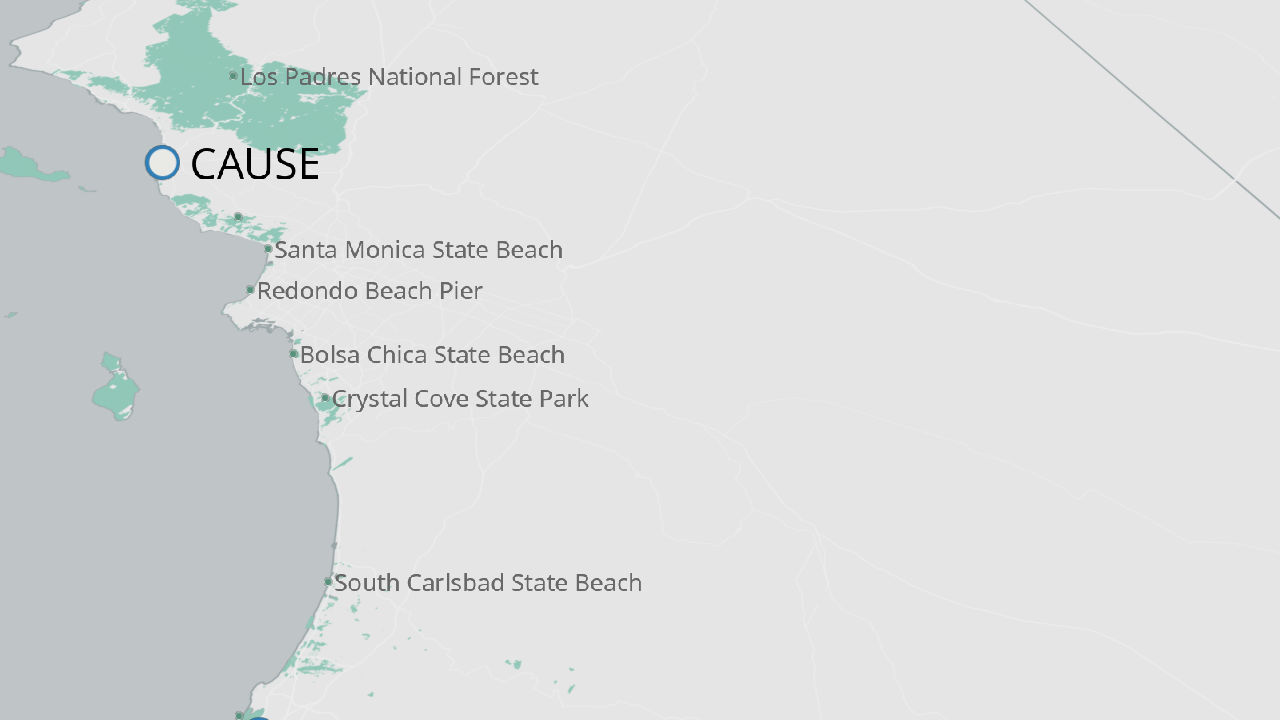

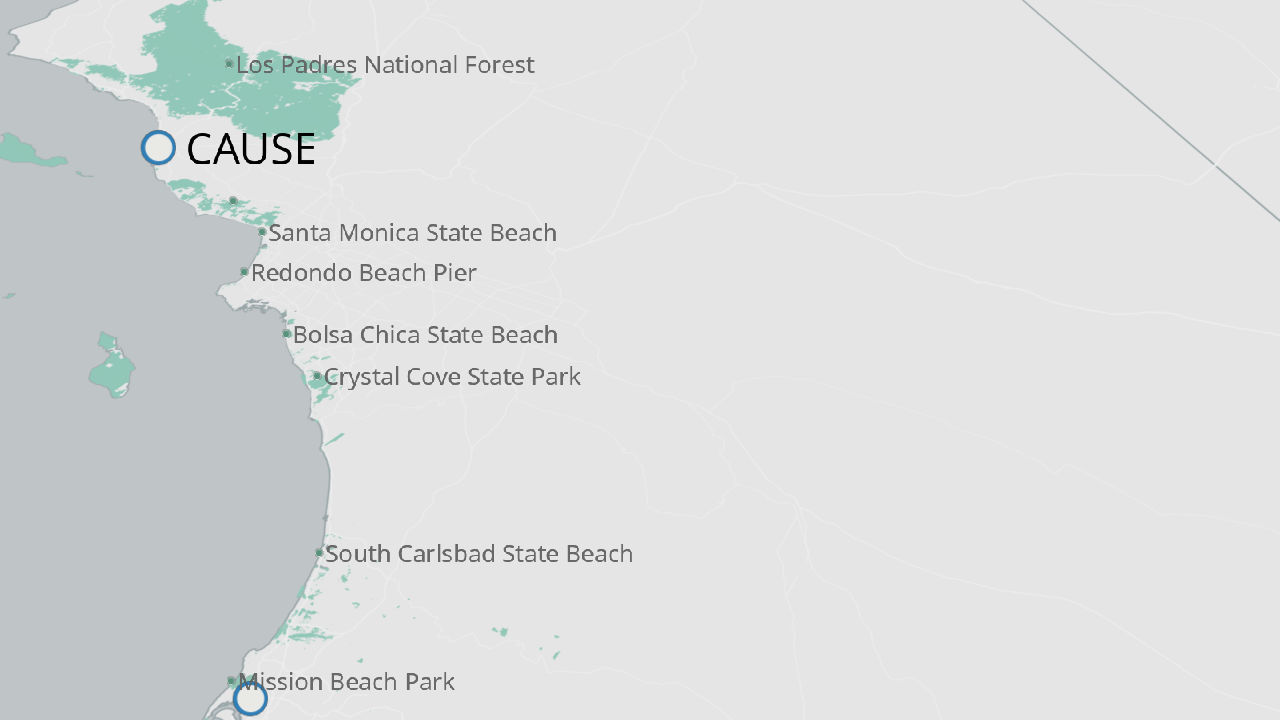

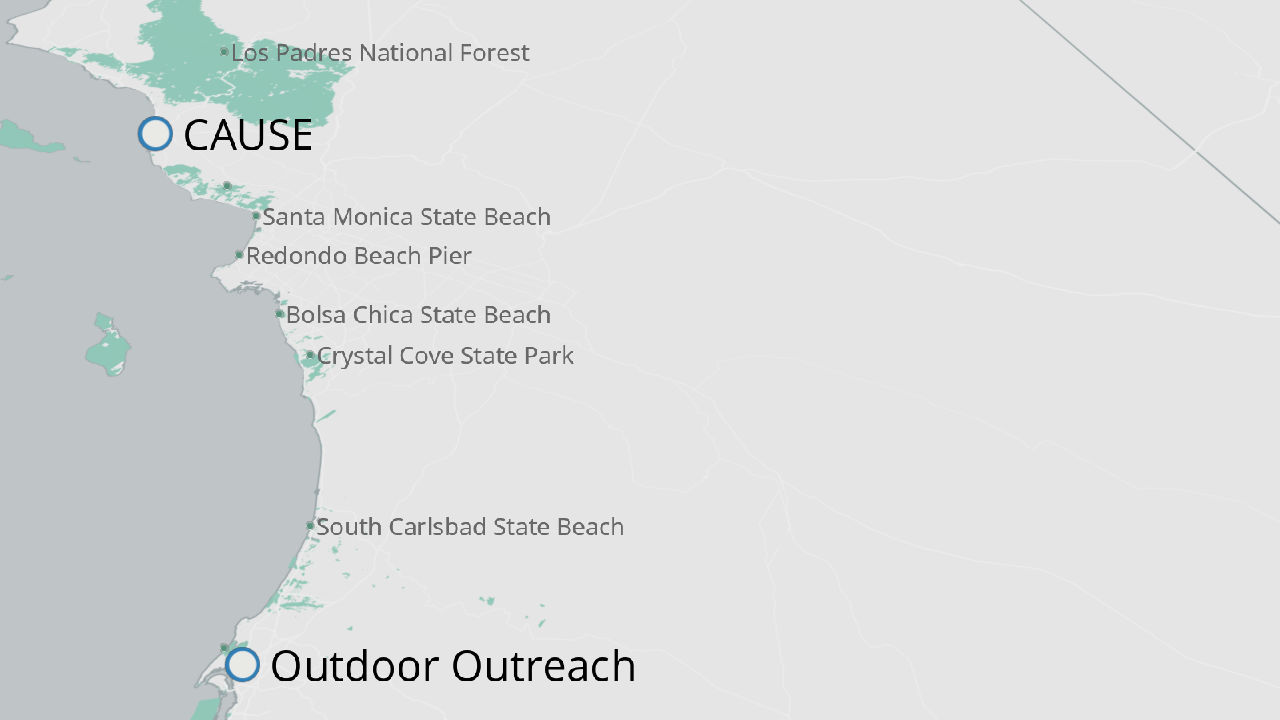

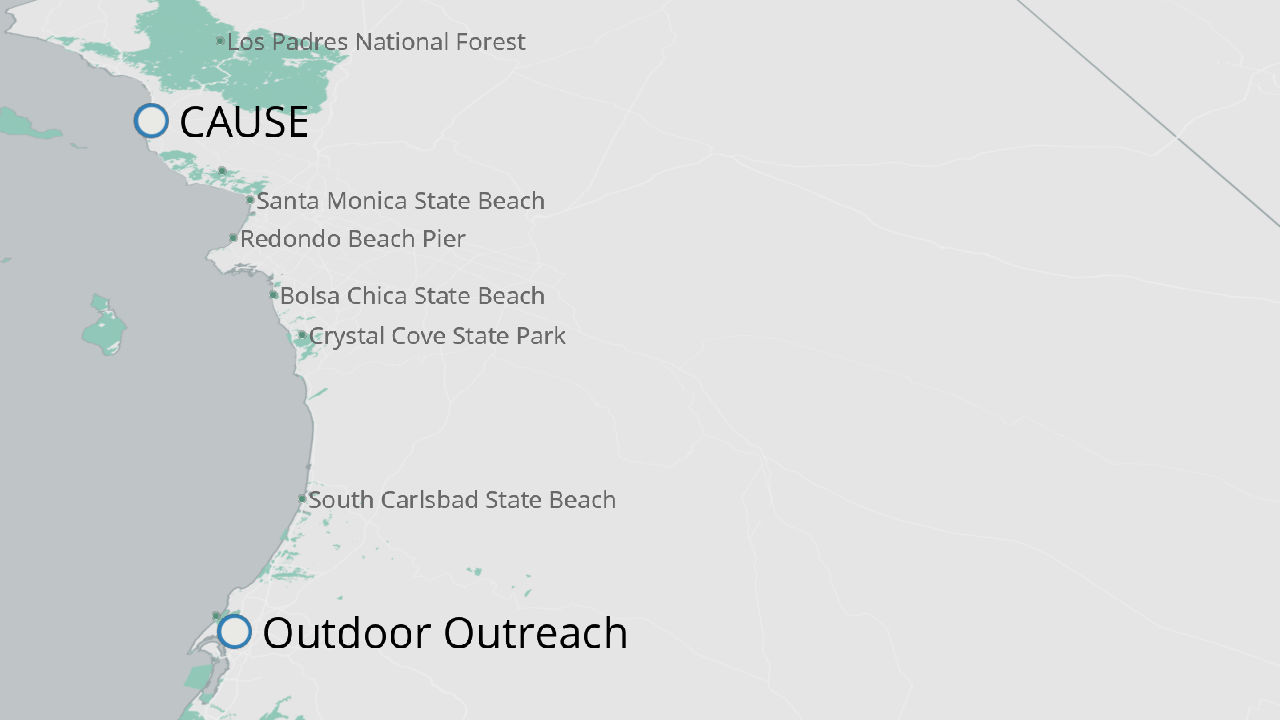

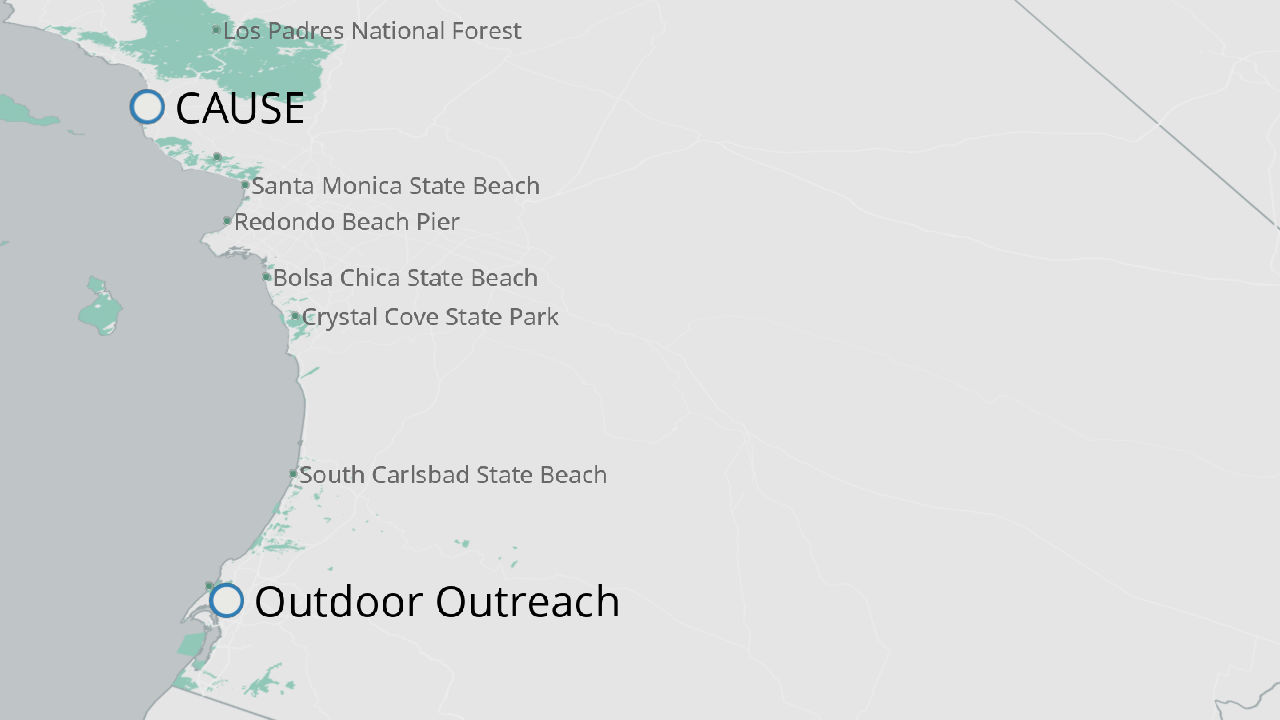

CAUSE (Oxnard)

CAUSE—the Central Coast Alliance United for a Sustainable Economy—is a grassroots organization that works to empower communities where all can contribute to, and benefit from, a sustainable economy that is just, prosperous, and environmentally healthy. CAUSE is organizing low-income communities to ensure that they have a voice in development decisions along the coast and enjoy the same kind of access to the coast and beaches as more wealthy communities.

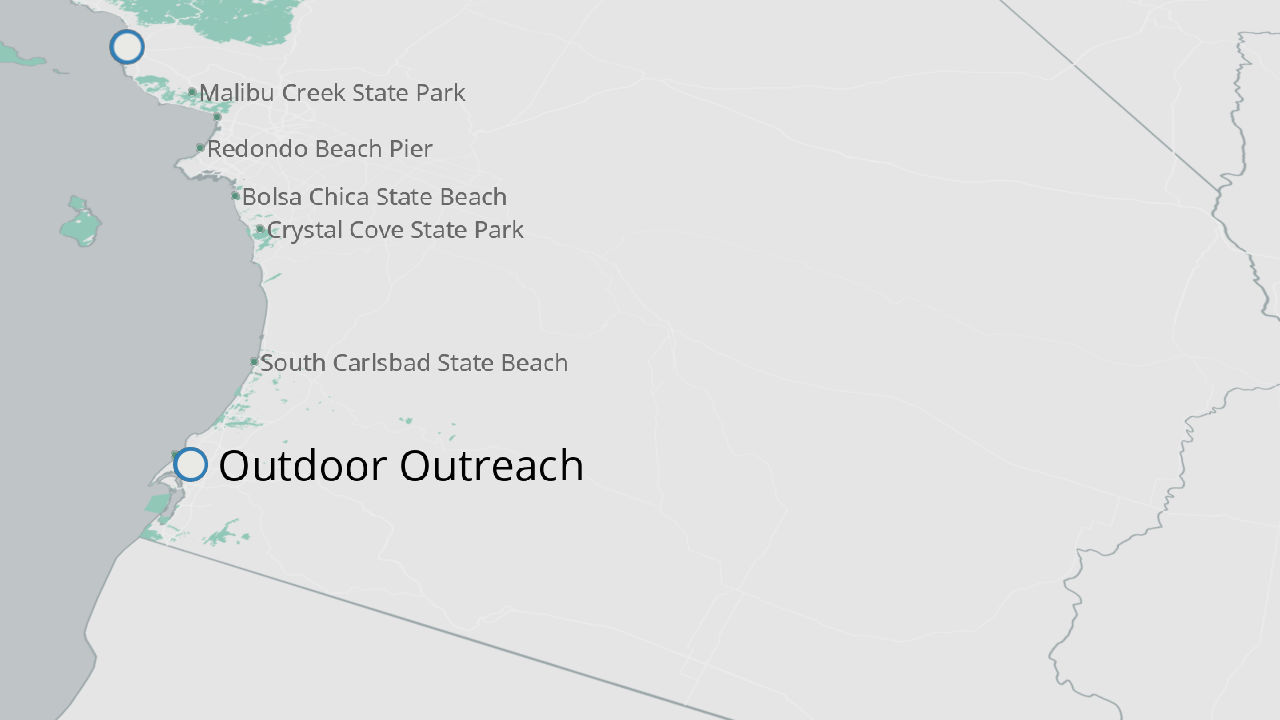

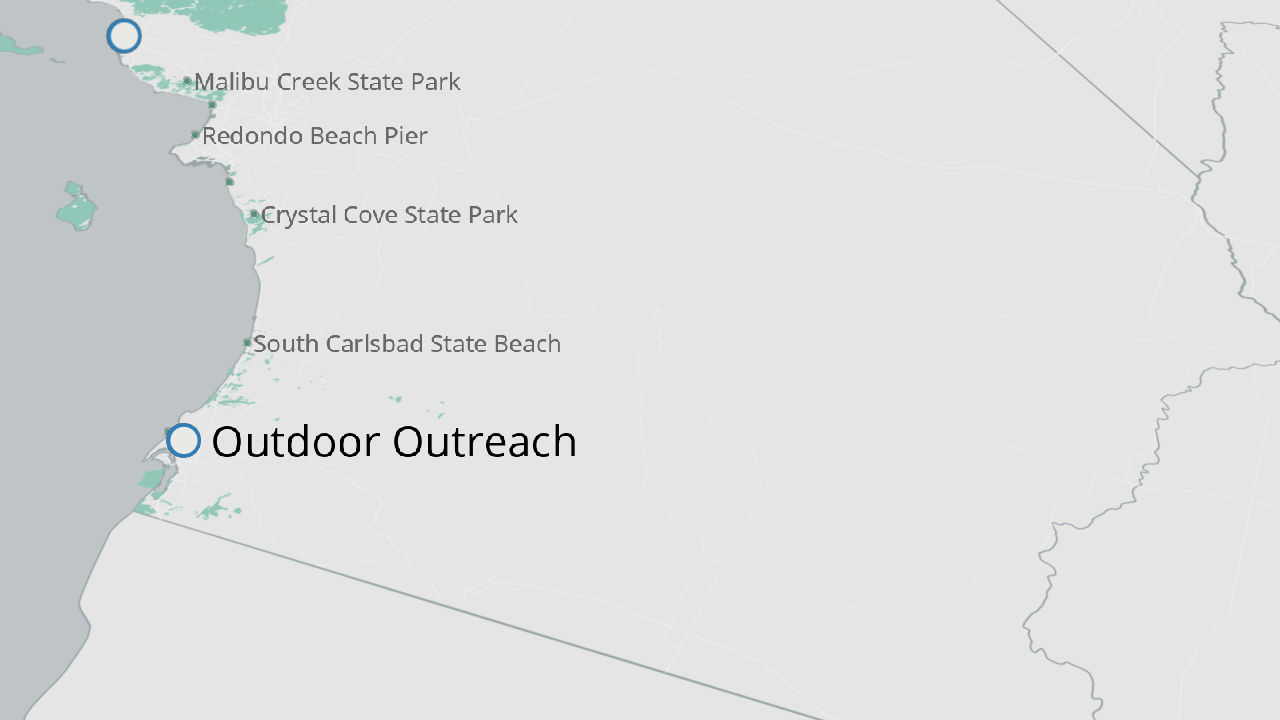

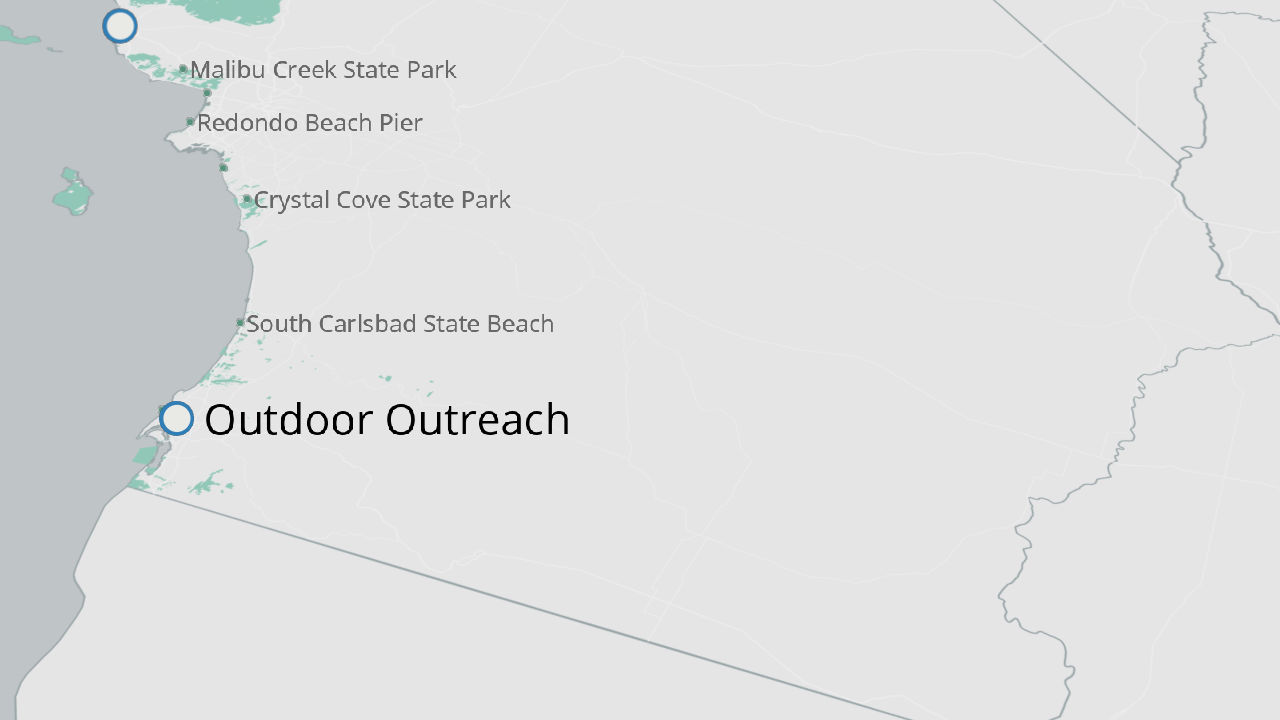

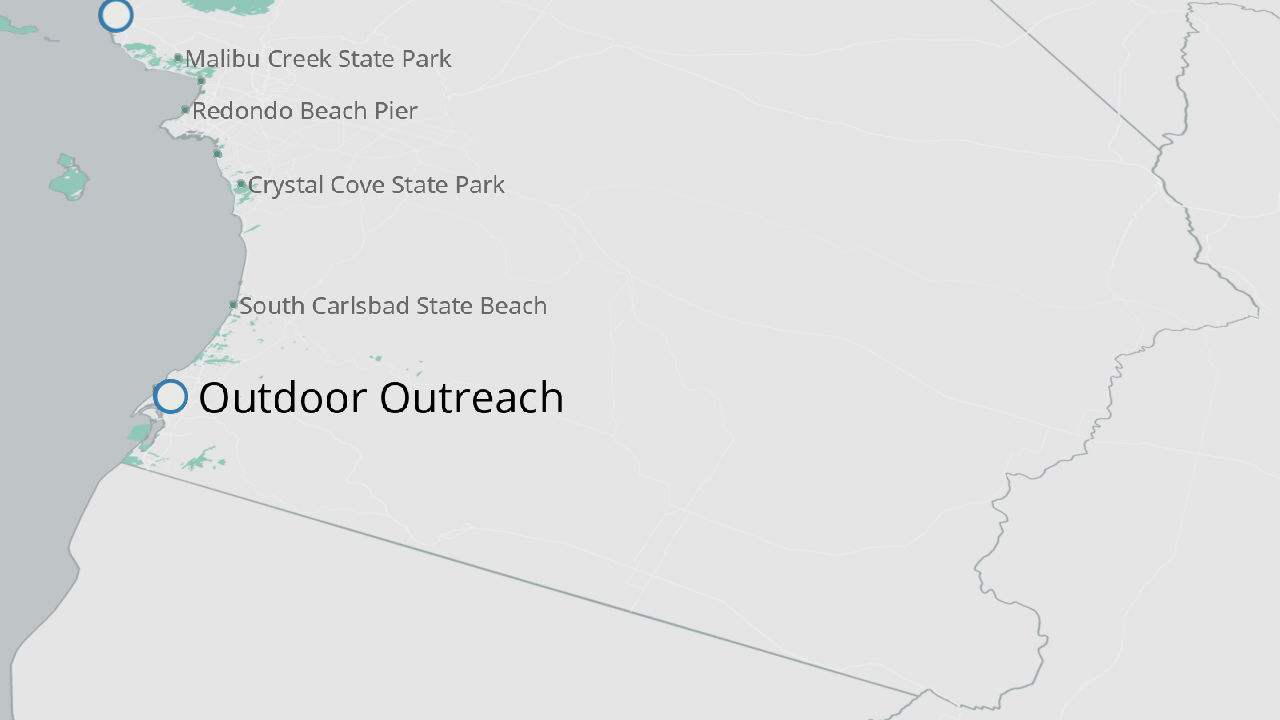

Outdoor Outreach (San Diego)

Outdoor Outreach has brought more than 9,000 youth into the outdoors in San Diego since its founding in 1999. Many participants come from low-income communities, and have few opportunities to experience natural parks and open-space areas before joining the programs.

Addressing the Next Generation of Coastal Access Issues

From the last hundred yards to access for all

The California coast and beaches are among our state's most important democratic spaces. Despite our differences, we all share a love of the coast and many of the same desires and reasons for coming to the beach. Under our state constitution and the California Coastal Act, our beaches belong to all of us. We need to make sure they are accessible to everyone.

Today's coastal access challenges will only be solved by collaborations among many institutions and groups. They can't be solved by the California Coastal Commission and Coastal Conservancy alone, although they could help to lead, inspire, and support many of the necessary solutions. To address the next generation of challenges to providing coastal access for all, we offer the following recommendations.

Recommendations

Focus legislative and executive branch attention on the coast.

Today's coastal access challenges are complicated. They will not be met without sustained, focused attention from the California Legislature and the executive branch of state government. Most importantly, California's leaders should understand that the coast is home to some of California's most valued public parks and open spaces—including the beach itself—and that millions of Californians of all backgrounds visit the coast each year, many from hours away. Updated and enhanced policies and funding are likely to be important strategies for improving coastal access. For example, California could allocate increased funding to public transportation that goes to beaches and coastal parks, as well as to development and improvement of affordable overnight accommodations and recreational facilities. California could also develop and support grant programs that help provide lower-income and middle-class families with outdoor educational opportunities along the coast. Such solutions could stand alone, or they could be elements of broader measures designed to enhance California's parks, transportation, and public health. Finally, California could ensure that coastal public access programs at agencies such as the Coastal Commission and Coastal Conservancy have sufficient staffing and resources to collect needed data about coastal users, develop and implement strategies to meet emerging public needs, and support local and nonprofit efforts to enhance access. Leadership is also important for coastal access: for example, new appointments to the Coastal Commission and other agencies with coastal management responsibilities should clearly understand California's demographic changes and evolving access challenges, as well as California's commitment to maximize public access to the coast for all. Finally, the Coastal Commission and Coastal Conservancy, despite their dedicated and often successful efforts, cannot do this alone. Other partners, such as the State Lands Commission and State Parks (managers of a third of California's coastline), local governments, the private sector, nonprofits, and philanthropic organizations will also have important roles to play. They should be encouraged and supported to take part in programs that protect and improve access to the coast.

Change the narrative of access.

For the first forty years of the Coastal Act, ensuring coastal access has been interpreted by many to mean providing direct physical access to and along California's publicly owned tidelands and beaches. Physical impediments to direct access remain, with some wealthy landowners illegally blocking the public from getting to the beach. The Coastal Commission and other agencies with coastal management responsibilities must remain vigilant in protecting public accessways to the beach. At the same time, more attention needs to be paid to providing adequate public transportation to the coast, increasing the availability of outdoor education and recreation opportunities, particularly for young people who have not experienced the coast, and the protection and provision of affordable recreational opportunities and overnight accommodations that meet the needs of lower-income and middle class families. This next generation of challenges will be more complex and require collaboration with many other players, from leaders in coastal and inland communities, to the private sector, government agencies, nonprofits, and philanthropic organizations, as well as the governor and legislators. The Coastal Commission and Conservancy should focus communication efforts on telling that story and on building effective partnerships in the coming years.

Protect and increase the supply of lower-cost overnight accommodations on the coast.

Solving this barrier is key to providing access to the coast for many Californians. It cannot be solved by the Coastal Commission and Conservancy alone, but they can and should lead the effort. The Coastal Commission is embarking on an effort to develop standards and policies for maintaining the existing supply of lower-cost overnight accommodations on the coast. With the Coastal Conservancy as a non-regulatory partner, along with other key partners such as State Parks, local park and open space agencies, and local governments, the Commission can help to stop the decline in the supply of lower-cost accommodations and increase that supply over time. Those efforts should be made a high priority and given adequate support to succeed.

Enhance options for getting to the beach using public transportation.

Low-cost express buses to the beach from inland communities in the San Fernando Valley have long been popular on summer weekends in Los Angeles and may be a good model for other areas. The last quarter-mile to the beach is also crucial. People do not want to walk more than a few blocks when they get to the coast, especially if they are loaded down with beach and picnic gear or accompanied by small children or elderly visitors. Public transportation needs to get to the beach. If it does not, a stop-gap solution, such as a shuttle across the last stretch, will likely be necessary for people who take public transportation to the coast.

Recognize that adequate and affordable parking is understood by many Californians as a critical element of coastal access.

Parking on the California coast is perceived as a problem by a majority of people from every corner of the state. Visitors want to park no more than a few blocks from the beach. And the average amount that they say they are willing to pay for parking is under $10 a day. At the same time, parking and daily use fees can help to pay for needed amenities that enhance visitors' experiences along the coast. User fees are part of the revenue stream that supports parks in California. The Legislature could provide better policy guidance for the fees set by State Parks, and the Coastal Commission could work with other agencies on the coast to establish more predictability for visitors in different regions of the coast. Increasing predictability in parking and day-use fees—and helping visitors understand what their fees pay for—could reduce uncertainty and confusion and increase support for reasonable fees if visitors understand how they are contributing to maintaining and improving coastal access.

Support groups changing the culture of access to the coast.

Dozens of groups up and down the coast are working in a variety of creative ways to promote coastal access and deepen the ties of diverse Californians to our coast and beaches. Groups such as Brown Girl Surf in Northern California and Outdoor Outreach in San Diego bring young people to the beach, including youth who live near the coast, but have never been to the ocean. The Central Coast Alliance United for a Sustainable Economy (CAUSE) is organizing low-income communities to ensure that they have a voice in development decisions along the coast and enjoy the same kind of access to the coast and beaches as more wealthy communities. There are many other nonprofit groups and parks and recreation agencies doing similar work in coastal and inland communities, and more are emerging all the time. These organizations depend on philanthropic and public funding for outdoor education and recreation programs. These programs need to expand beyond coastal communities and counties to help inland communities, particularly young people, gain access to and experience the California coast. The future of California's passion for protecting and enjoying our coast and ocean will depend on them.

Credits

This report was written by Jon Christensen, adjunct assistant professor at the Institute of the Environment and Sustainability at UCLA, and Philip King, professor of economics at San Francisco State University. The analysis was conducted by Christensen, King, and Craig Landry, professor of economics at the University of Georgia. This interactive report was designed and built by GreenInfo Network using Esri ArcPro as well as open source software, with design consulting by Bixler Communications. This research was conducted under a grant from Resources Legacy Fund. For more information, contact jonchristensen@ioes.ucla.edu.